Texas primary spurs flurry of activity at the polls

| Austin, Texas

Democrats in deep-red Texas turned out Tuesday in the largest numbers in more than two decades for a midterm primary election, propelling women candidates toward challenges to entrenched male Republicans in Congress and venting their anger at President Trump in the first state primary of 2018.

The biggest question was whether Texas is just the start of what's to come nationwide. Energized Texas Democrats showed up despite the long odds this November of ousting Republicans such as US Sen. Ted Cruz – who released a radio ad after clinching the GOP nomination Tuesday night, telling voters that Democratic opponent Beto O'Rourke "wants to take our guns."

Mr. O'Rourke, a congressman from El Paso, has called for banning AR-15-style assault rifles in wake of last month's mass shooting at a Florida high school that killed 17 people.

Neither that tragedy nor a mass shooting at a Texas church last fall played as dominant campaign issues in Texas, but with the GOP's majority in Congress on the line this fall, Democrats came out in force. Republicans kept their edge in the total number of votes cast although Democrats made significant inroads in what had been a lopsided GOP dominance for decades.

Democrats have their sights on flipping three GOP-controlled congressional seats in Texas that backed Hillary Clinton over Mr. Trump in 2016, including a Houston district where two women were the top vote-getters in a race likely to go to a May runoff. Another is a sprawling district that runs along the Texas-Mexico border, where Gina Ortiz-Jones advanced to a May runoff and another woman, Judy Canales, was battling to join her.

"I think that a Congress that is only 20 percent women is not where we need to be," Ms. Ortiz Jones told The Associated Press on Tuesday night. "This is not a spectator sport, we've got to participate, all of us and that's what's important."

It was also a big night for two Hispanic women, Veronica Escobar and Sylvia Garcia, who won their Democratic primaries and are poised to become the first two Latina congresswomen in a state where a population boom has been driven by Hispanic growth.

College students waited more than an hour to vote in liberal Austin and rural counties offered Democratic candidates for the first time in years. A tide of anti-Trump activism helped propel nearly 50 women to make a run for Congress. Many were running in a record eight open congressional races this year in Texas – two of which are up for grabs after longtime GOP incumbents abandoned plans for re-election amid scandal.

More than 1 million Democrats cast ballots in the midterm primary for the first time since 2002, which were the first elections after the Sept. 11 attacks. Democrats, who once dominated Texas politics, would have to go back to 1994 to find more voters casting ballots for their party candidates. Since then it has been all Republicans, who have held every statewide office.

There was some good news for Republicans. They cast a record 1.5 million ballots Tuesday, topping the previous GOP record in 2010, and suggesting that voters on both sides were motivated. But the increase in participation was much greater for Democrats.

While 2002 was a recent high water mark for Democratic turnout in Texas, it also showed the limits of the exuberance for turning the state blue. In November that year, the Democrats running for statewide office were all beaten.

For Republicans, the primary was a vivid exhibition of the Trump effect in GOP politics. George P. Bush, the Texas land commissioner, won a contested primary after he cozied-up to a president who once called his dad, Jeb, a pathetic person. Kathaleen Wall, a former GOP megadonor running for Congress in Houston, was also in the hunt for a runoff after she ran TV ads that suggested there was little daylight between her and Trump.

Trump won Texas by 9 points in 2016. It was the smallest margin of victory by a Republican presidential candidate in Texas in 20 years, but Mr. Cruz dismissed talk of a Democratic takeover this fall.

"Left-wing rage may raise a bunch of money from people online, but I don't believe it reflects the views of a majority of Texans," he told reporters after winning the nomination.

The surge of Democratic voters included some former Republicans switching this cycle, including 61-year-old Sarah Chiodo of Dallas, who said she changed parties after Trump was elected.

"I hope that our political environment changes. I'm not happy with it today," she said after voting at a Dallas church. "I find it very divisive and dividing of many people and negative. So I'm looking to vote for people who are positive who care about all."

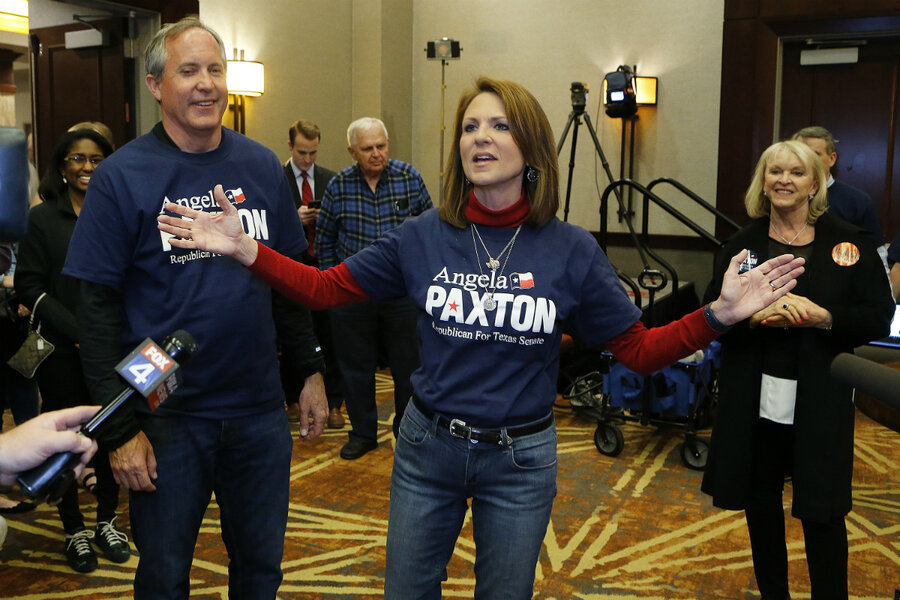

Democrats will have a tough time winning statewide races in November despite the "Trump effect" because they have fielded little-known candidates against top Republicans, such as Republican Gov. Abbott and Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick. Even Attorney General Ken Paxton, who has been indicted on felony securities fraud charges, clinched his party's nomination unopposed.

Mr. Abbott will face either Lupe Valdez, who was Texas' first Hispanic, lesbian sheriff, or Andrew White, who opposes abortion and whose father, Mark, was governor in the 1980s.

In a closely watched Democratic race, congressional hopeful Laura Moser, who moved from Washington to her native Houston and was in contention for a runoff to challenge US Rep. John Culberson. The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, fearing Ms. Moser would be a weak candidate in the general election, blistered her for comments from a 2014 Washingtonian magazine article in which Moser said she'd "rather have her teeth pulled out" than live in rural Paris, Texas.

This story was reported by The Associated Press.