Urban Democrats see new opportunities in midterm elections

As Dallas has evolved from reliably red to deeply blue, joining many other big cities, one enclave has remained the beating heart of country club conservatism – home to Cowboys owner Jerry Jones, oil tycoon T. Boone Pickens, and former President George W. Bush.

Just north of downtown, it's where suits-and-cowboy-boots culture meets the high-powered banking circuit and Southern Methodist University's immaculately manicured campus.

Still, this longtime Republican stronghold could now help determine whether Democrats can break the GOP's control of Congress. If Republicans lose their 23-seat margin in the House in this fall's election, as some GOP leaders fear, the swing may be built on unlikely urban and suburban areas like this, where until recently Democrats couldn't even muster credible candidates – but that have slowly become more diverse, well-educated, and politically competitive.

Now considered key battlegrounds are exclusive Dallas haunts and mini-mansion-lined blocks of Houston, the oceanfront condos in Miami's South Beach, and the mountain-flanked California home of Ronald Reagan's presidential library. Also possibly in play are a district north of Milwaukee that's backed a Democrat for Congress just once since World War II, and one anchored in Cincinnati that's been Republican since native son William Howard Taft became president in 1909.

Nationally, the Republican Party relies on white voters, who account for 86 percent of its totals. More than half are whites without a college education. Democrats run stronger among ethnic minorities and the college educated. As cities have become magnets for minorities and young professionals, the GOP has compensated by peeling off congressional districts in some white, blue-collar places like upstate New York, northern Michigan, and southern West Virginia.

But this year the balance seems to favor Democrats. In addition to the traditional fall-off in support for the president's party in midterm elections, three dozen-plus House Republicans have decided to retire, opening up more opportunities. Also, while President Trump remains strong in rural areas, his popularity is weakening among women and college-educated Republicans, including those in upscale neighborhoods.

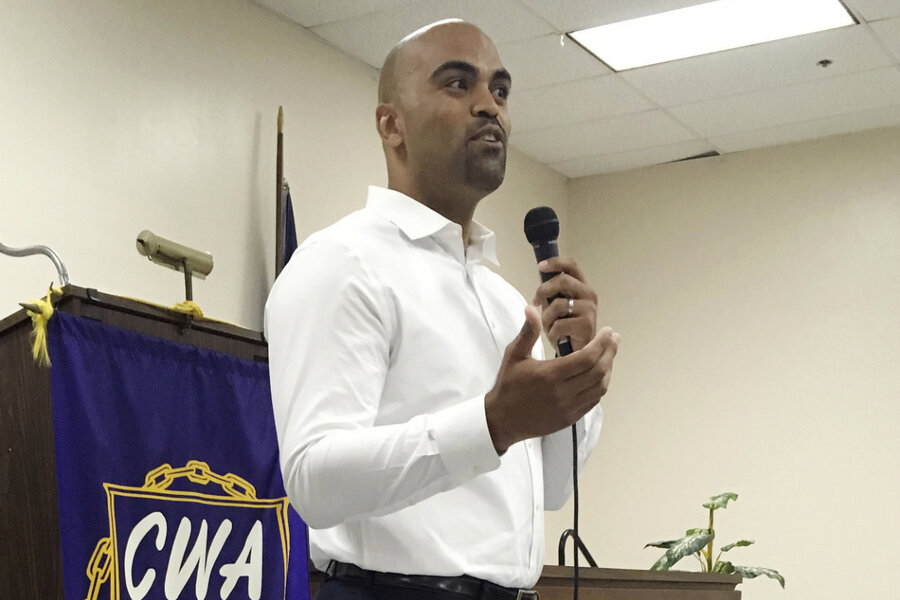

In Dallas, Colin Allred, a former Tennessee Titans linebacker and civil rights attorney, is hoping to oust 11-term Republican Rep. Pete Sessions, whose seat is considered among the vulnerable.

"This is a highly educated district with a lot of people who are paying attention," Mr. Allred said. "And a lot of those people don't like what they're seeing."

First elected to Congress in 1996, Mr. Sessions is so entrenched that he didn't face a 2016 Democratic challenger. But Hillary Clinton narrowly defeated Mr. Trump in his district, which had backed Mitt Romney by 15 points in 2012. Representative Sessions' territory is now more than a quarter Hispanic and nearly another quarter black and Asian.

Allred was raised in Dallas by a single mother. A neck injury ended his five-year NFL career in 2010, but he used savings from his NFL salary to pay for law school before serving in the Department of Housing and Urban Development during former President Barack Obama's administration.

Sessions, a prolific fundraiser, says he's not worried because his territory remains full of Texans who reject "the big government shackles that liberal Democrats always try to force on us."

Allred still has to win a May 22 Democratic runoff against Lillian Salerno, a fellow veteran of the Obama administration who finished nearly 20 points behind him in the primary last month. Allred raised $400,000-plus in the year's first three months while Sessions got $600,000-plus.

National Democrats are investing in the race. The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee has been buying anti-Sessions digital and radio ads for the last year. It also has full-time organizers in Dallas, Houston, and 18 other GOP districts.

The prospect to flip in Houston is Rep. John Culberson's affluent district, which has voted Republican since first sending President George H.W. Bush to Congress half a century ago. But Ms. Clinton beat Trump there in 2016, and it's now nearly a third Hispanic, while about a fifth of residents have postgraduate college degrees.

"The socio-economic fabric of the district has changed," said Mustafa Tameez, a Houston-based political strategist who has worked for Democratic candidates but also was a homeland security consultant for George W. Bush's administration.

To counter the Democratic push, the Congressional Leadership Fund, a political group with ties to the outgoing House Speaker Paul Ryan, has opened a field office in Representative Culberson's district – one of nearly 30 the group now has protecting Republican House incumbents nationwide.

Shifting demographics are also challenging for veteran Republican Rep. Steve Chabot of Cincinnati. Traditionally white and heavily Catholic neighborhoods have become more racially mixed, while the center city has seen an influx of young, well-educated professionals.

For a Democrat, "It's still an uphill climb," said Caleb Faux, executive director of the Hamilton County Democratic Party, but he noted that Aftab Pureval, an Indian-American Democrat challenging Representative Chabot, won a county position in 2016 that had been Republican-held for a century-plus.

Other districts in flux include Republican Rep. Steve Knight's, encompassing part of Los Angeles County and Ronald Reagan's presidential library in Simi Valley. It hasn't voted Democratic since 1964 but has a swelling Hispanic population. In Miami, Republican Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen is retiring after 30 years in Congress, creating an opportunity in a district where Clinton beat Trump by 20 points. A parade of top Democrats, including former US Health and Human Services Secretary Donna Shalala, is vying for the party's nomination.

Wisconsin Rep. Glenn Grothman's rural-suburban seat has been GOP-controlled since 1967, but Mr. Grothman admits he's "very apprehensive about the future."

Back in Dallas, some, like retiree Julie Bengtson, see similar, once unthinkable trends.

Ms. Bengtson was a Republican for decades but skipped sending Christmas cards last year to avoid political discussions with Trump-supporting friends. She said she's now finding more friends uncertain about their votes.

"Even in our area, it's happening," Bengtson said. "More and more people are leaving the party."

This story was reported by The Associated Press.