In West Virginia, GOP tries to tame forces of 'Trumpism'

Loading...

| Washington and Bluefield, W.Va.

In more conventional times, Don Blankenship would be nobody’s poster boy for a successful US Senate candidate. He’s an ex-con who doesn’t smile much, uses racially tinged language, and maintains his primary residence three time zones away.

But the West Virginia coal baron is also wealthy, speaks his mind, bad-mouths the GOP establishment, and wants to make America great again – just like another first-time candidate named Donald who rode that message all the way to the White House a year and a half ago.

And like President Trump, Mr. Blankenship is poised for a possible upset win – at least in the Republican primary. Blankenship is surging in polls ahead of Tuesday’s vote, GOP strategists say, and in a crowded field, he could capture the nomination with a plurality. That would spell a major missed opportunity for the Republican Party in November, making a vulnerable Democrat – Sen. Joe Manchin – far more likely to win reelection.

Why We Wrote This

Anti-establishment furor helped propel Donald Trump into the White House – but can the president control the political forces he’s unleashed? GOP leaders are furiously trying to halt the momentum of former coal magnate Don Blankenship, a West Virginia Senate candidate who calls himself “Trumpier than Trump,” and who spent a year in prison after an accident killed 29 workers in one of his mines.

“Remember Alabama,” Mr. Trump tweeted Monday, a reference to Democrat Doug Jones’s own improbable Senate victory last December against a controversial Trumpian Republican, Judge Roy Moore. Trump also stated that Blankenship can’t win in November.

Trump’s tweet, coming on the heels of several by his oldest son, Donald Trump Jr., attacking Blankenship last week, represents a remarkable turn for a president who is now essentially campaigning against his own revolution. Trump has inspired countless novice candidates across the country, who see no limit to their ability to win public office at a time when Americans are tired of politics as usual and have lost faith in government and other institutions.

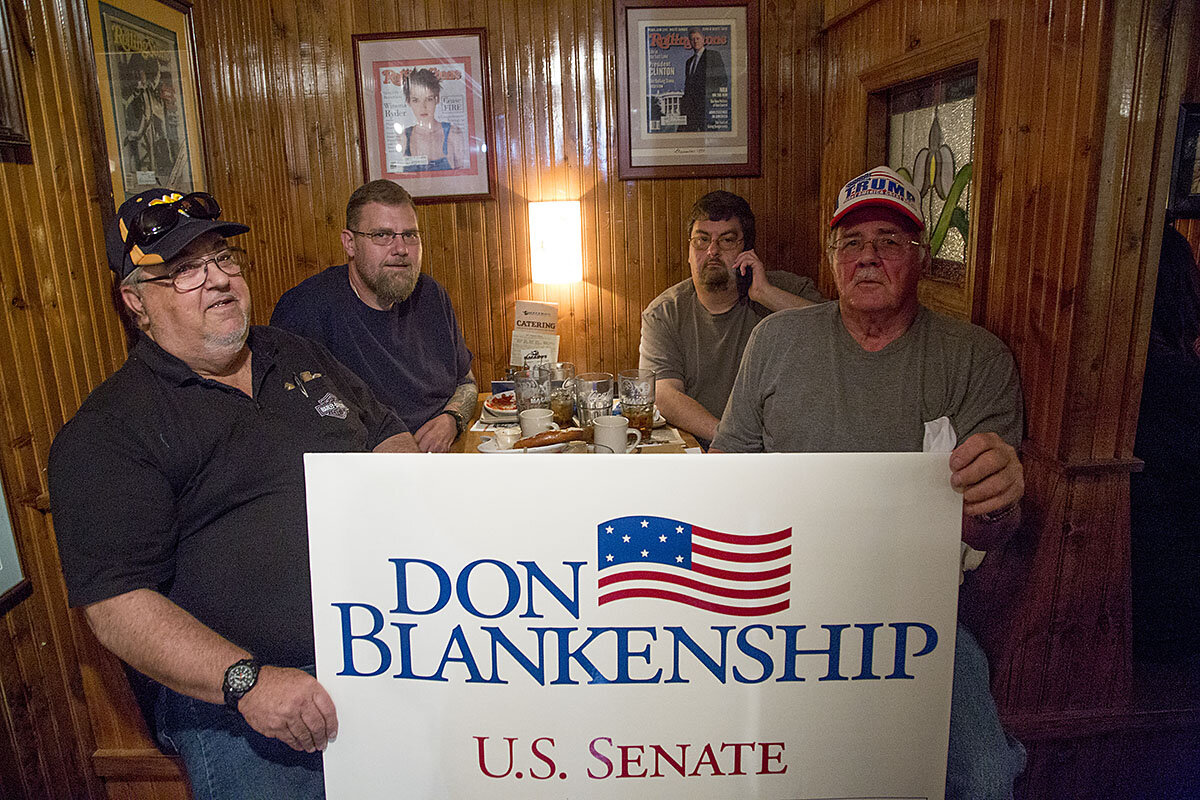

Here in Bluefield, a coal-mining town in the rolling hills near the Virginia border, voters who’ve come to hear Blankenship are eager to see a Republican win in November. But they’re also thinking: Who speaks for me? After a Fox News debate last week in which the top two GOP candidates went after each other, some began moving toward Blankenship, who until recently was placing third in polls.

“A month ago, I’d probably have voted for Morrisey,” says retired coal miner Ron Thompson, referring to state Attorney General Patrick Morrisey, a tea party Republican.

Now, Mr. Thompson says, he’s leaning toward Blankenship. Thompson appears unfazed by the 2010 accident at Massey Energy’s Upper Big Branch coal mine when Blankenship was Massey CEO, which killed 29 men in the deadliest mining accident in 40 years. Blankenship claims his prosecution over the disaster and the year he spent in prison were unjust.

Thompson seems to agree. “People got killed, it happens,” he says. “Somewhere down the line, somebody wasn’t doing their job.”

The fact that the wealthy Blankenship now maintains his primary residence in Nevada, and that he uses racially tinged language when speaking of Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell’s in-laws, who hail from Taiwan, doesn’t come up in conversations with voters.

Blankenship’s message centers on jobs, schools, guns, abortion, and the opioid epidemic. And he insists he’s not running as a carbon copy of Trump. “I think [Trump] shoots from the hip a lot. I’m far more analytical,” Blankenship told a reporter after the Bluefield town hall.

But he’s definitely tapped into the same anti-establishment, anti-Washington strain of thought that propelled Trump to the presidency. The other leading candidate in the GOP primary here, Rep. Evan Jenkins, has the backing of the party establishment. If Morrisey or Congressman Jenkins wins on Tuesday, either would have an excellent shot at defeating Senator Manchin in November. And that would set back the Democratic goal of retaking the Senate, which Republicans currently control with just a 51-49 majority.

Blankenship announced his campaign only in January, but spent his own money on TV ads, quickly reintroducing himself to voters and boosting attention to his message. And if there’s a definite Trumpian strain to Blankenship’s appeal, which is blunt and plainspoken, it comes with a West Virginia twist, born of his upbringing here. Unlike Trump, Blankenship was raised by a single mom, and came up poor.

The man who would become known as the King of Coal used an outhouse in his childhood, he said in a brief interview with the Monitor after the event. When he got a job in the coal mines as a teenager, he reveled in being able to shower in a heated room. And while he now enjoys a far more luxurious life, he is conscious that many in his state are growing up in similar circumstances. One year, he had his team ask schoolchildren in Boone County what they would like for Christmas, and several of them said groceries.

“There’s a rural populism that Don Blankenship in many respects embodies,” says Steve Roberts, president of the West Virginia Chamber of Commerce, whose political action committee endorsed Jenkins. “He does speak for a populist point of view, and these are not new positions [for him]. He’s always been more interested in fair trade than free trade.”

Blankenship also isn’t somebody who “tries to hide,” says Mr. Roberts, who has known Blankenship for years. In last week’s debate, “he didn’t say, ‘No, I don’t own a home in Las Vegas,’ ” Roberts notes. Blankenship acknowledged that fact, and added that he probably pays “more taxes than anybody on this stage to West Virginia,” eliciting cheers from the audience.

Blankenship does push back on his role in the Upper Big Branch mine disaster. He was convicted of conspiring to violate federal safety standards, a misdemeanor, and served one year in federal prison. On the trail, he has recast that episode into a talking point, calling it a “frame job” and blaming the Obama Department of Justice.

But in Whitesville, the town of about 450 in Boone County where the accident occurred, Blankenship is not remembered fondly by some.

“He’s a smart businessman, but he is absolutely ruthless,” says a former manager who worked for Blankenship for nine years. He requested anonymity because he is now a federal employee and is barred from partisan commentary.

Still, some Republicans say his opponents aren’t any better.

“There is three of the worst candidates I’ve ever seen to replace him,” says Deke Mylam, who says he has only voted for a Democrat once. “[Blankenship] is a known criminal whereas the other two are suspected criminals.”

Indeed, the other two major Republicans in the race also have image challenges. Morrisey is originally from New Jersey – making him “an outsider” – and was a lobbyist in Washington. He and his wife both did work for pharmaceutical companies, and as attorney general he has come under fire for not taking a harder line against drug companies that poured prescription opioids into the state hardest-hit by the opioid crisis.

Jenkins’s “sin” is that until 2013, he was a Democrat. That’s easy to explain, in a state that until fairly recently was solidly Democratic, but has swung hard toward the Republican Party. Trump won the state in 2016 by 42 points. Jenkins is also a sitting member of Congress, one of the most unpopular institutions in the country.

A super political action committee aligned with Senator McConnell has run ads against Blankenship, who referred to the majority leader’s wife’s family as “China people” and dubbed McConnell “Cocaine Mitch,” apparently over a controversy involving his in-laws’ shipping company. He then reportedly used the term “Negro” while defending himself against charges of racism. Other outside groups seeking to sway the primary have added to the free-for-all feel in the final days – including national Democrats attacking both Morrisey and Jenkins, in an apparent effort to boost Blankenship.

Trump, for his part, told voters in his tweet Monday to vote for either Jenkins or Morrisey. But the danger is that the mainstream GOP vote winds up divided between those two, allowing Blankenship to win with as little as 35 percent.

Local political analysts say it can’t be overstated how tired West Virginians are of politics as usual.

“Since at least John F. Kennedy, West Virginians have had politicians come to the state and say, ‘I have a plan to fix things.’ And they haven’t fixed it yet,” says Patrick Hickey, a political science professor at West Virginia University. “So people have become very skeptical of government, and skeptical of traditional politicians. And that’s where Blankenship’s appeal lies.”

Back in Bluefield, voters at the town hall gathered over gigantic Cobb salads and plates of fried food – courtesy of Blankenship – and talked about hot-button issues, from abortion and underfunded schools to the national debt and the poor standard of living in West Virginia, where some folks still don’t have indoor plumbing, clean drinking water, proper sewer lines, or reliable cellphone and high-speed Internet service.

But most of all, they seem fed up with the politicians in Washington. And so, on the coattails of one outsider’s ascension to the White House, they’re looking to catapult another into the Senate – to further disrupt things for members of the establishment.

“They don’t like non-politicians coming and upsetting their apple cart,” says voter Allen Vest of Princeton, W.Va., who says he became intrigued by Blankenship during the Fox debate last week.

“I just saw two kids pointing fingers at each other, and one man trying to talk,” Mr. Vest says, contrasting Blankenship with opponents Morrisey and Jenkins. “He’s got an uphill battle, but I’m going to support him.”