Can the center hold? Susan Collins and the high wire act of being a moderate

| Winterport, Maine

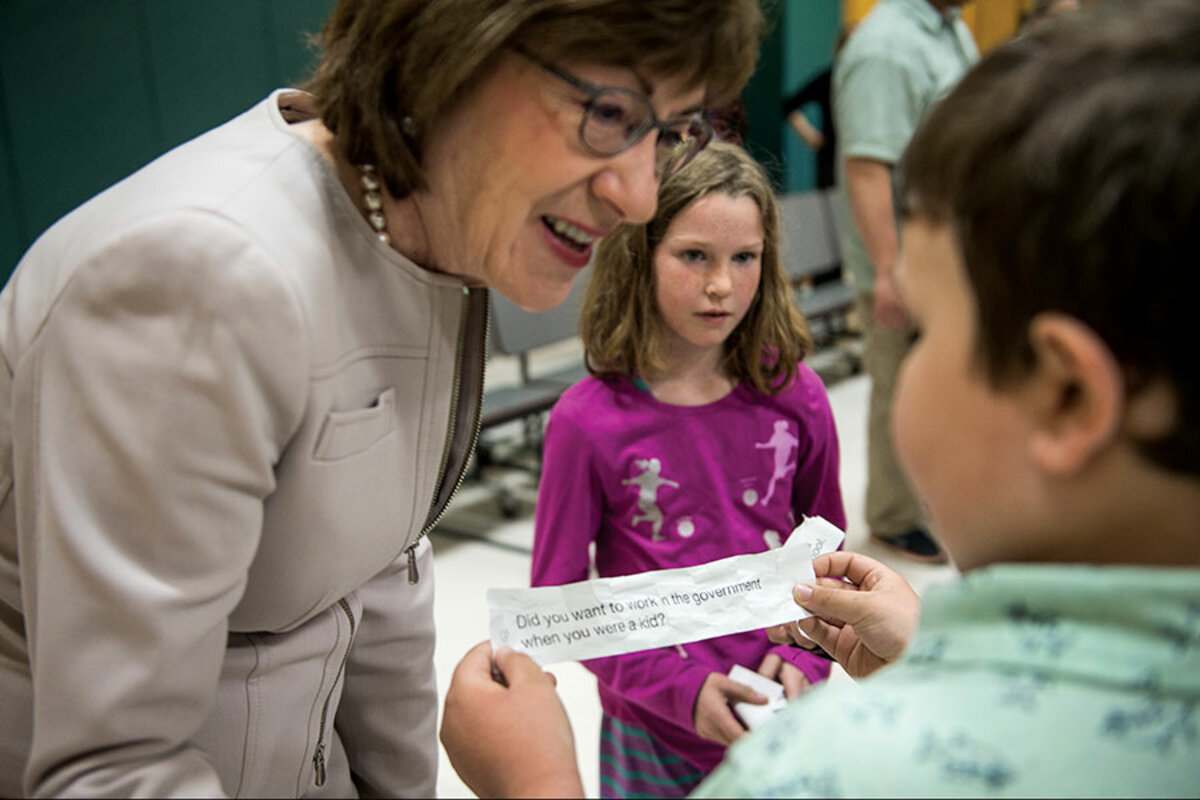

On an overcast morning this spring, Maine’s Republican Sen. Susan Collins is visiting with students in grades 2 through 4 at the Leroy H. Smith School here in Winterport, just outside Bangor. The children have filed into the school gym and sit cross-legged on the wooden floor as she narrates a “day in the life” slide show of her job as a United States senator.

She is in teacher mode, engaging her young audience. Here she is at a bill-signing ceremony with President Barack Obama (and who is that on the other side of the president? That’s right. Michelle Obama!). Here she is in a puffy parka visiting Antarctica – and penguins, too (they’re really cute but they stink!). In another shot, she’s christening a Navy ship built at Maine’s Bath Iron Works. She smashes a bottle with such enthusiasm that the contents spray her and other dignitaries. The kids laugh.

After the lights come up, it’s time for questions, which the children read from cards. What’s your least favorite thing about your job? Traveling back and forth to Washington, she says. Why do you want to be a senator? She gives a few examples of helping people – writing a law so teachers who pay for school supplies can get a tax break, and directing federal funds to build roads and bridges. Then she says:

Why We Wrote This

In a hyperpartisan Washington, centrists like Maine’s Senator Collins are both more isolated and more powerful than ever. This special report – the result of months of reporting and exclusive interviews – examines the arc of Collins’s career and whether her brand of moderation is becoming a relic of the past or holds the key to the future.

“I like that feeling of being able to make a difference.”

It’s an answer any lawmaker might give to a class of attentive, idealistic grade schoolers. But in Senator Collins’s case it may be more true than they know, more true than she intended. As one of the few remaining centrists in the nation’s capital, Collins has become a pursued – and highly pressured – political figure: Someone in a narrowly divided US Senate who holds considerable power to make a difference one way or the other on legislation, nominations, and policies.

It happened in 2017 with the Affordable Care Act (ACA), when she bucked her Republican colleagues in their attempt to repeal President Obama’s signature health-care measure, drawing plaudits from the left and sharp criticism from the right. It happened later that year when she sided with her GOP colleagues to help pass the Republican tax cut, which caused progressive activists to occupy her offices in Portland and Bangor. Now it’s happening again with the fight over the confirmation of Judge Brett Kavanaugh to the US Supreme Court.

Liberal interest groups are urgently pressing the senator, who supports abortion rights, to reject the conservative judge, who many believe will tilt the court decisively to the right on a number of issues including, most notably, Roe v. Wade. At the same time, Republicans are hoping she’ll find nothing in the coming weeks to dissuade her from her view – so far – that the jurist is “clearly qualified.”

It is a role Collins is intimately familiar with: being in the middle. The senior senator from Maine is a moderate in a nation that increasingly eschews moderation.

The evolution of her career, in fact, offers a window into how the politics of Capitol Hill has changed over the decades and maybe a glimpse into where it’s going. From a congressional internship during Watergate, through the impeachment proceedings of President Bill Clinton, to 9/11 and the tumult of the Trump presidency, Collins has served on the Hill through some of the most important events of the past 40 years. She has also watched as politics in the nation’s capital has become more polarized and pugnacious.

In one of several exclusive interviews, she describes today’s atmosphere in the Senate as “poisonous” – a strong condemnation from a practitioner of politeness who watches her words carefully. Lawmakers’ intense focus on the midterm elections is causing “good policy” to be politicized and die. “Even people I’ve worked with for many, many years are falling into that trap,” she says.

Throughout her political career, Collins has tried to position herself as a bridge builder. Other senators, to be sure, reach across the aisle. This includes a number of the women in the Senate, with whom Collins is close. “I love Susan to death,” says Sen. Heidi Heitkamp (D) of North Dakota. “She’s not just my friend. She’s my role model.”

Collins stands alone, however, as the Senate’s most bipartisan member, awarded that ranking five years running by The Lugar Center and Georgetown University. In her 21 years in the upper chamber, she’s never missed a vote, and she’s the highest-ranking woman in the GOP Senate caucus.

Certainly Collins has her detractors, in Maine and Washington, as well as her ardent supporters. Some see her as an anachronism: neither conservative nor progressive enough to satisfy the increasingly belligerent wings of either party. Others see her brand of centrist politics as the answer to what’s ailing the nation, someone willing to put problem-solving above the unyielding tribalism of today.

“Centrists are not a dying breed, but they need to be nurtured, just like any endangered species,” says former Sen. Barbara Mikulski (D) of Maryland, who lauds her friend’s ability to pull people together. “The new wave of politics that’s coming really demands that people start ending the gridlock, the deadlock, and obnoxious behavior.”

Does Collins represent the future or a relic of the past?

***

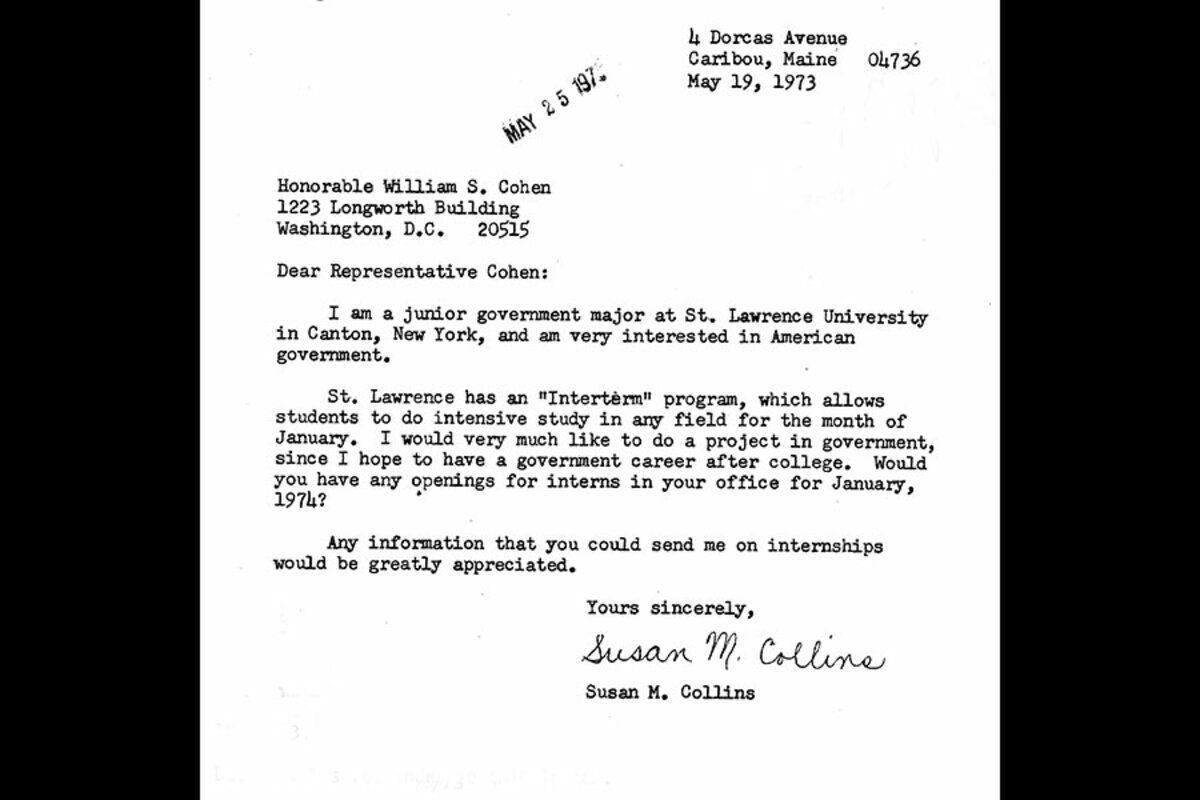

Collins’s Capitol Hill career almost got lost in a drawer. Her letter inquiring about an internship in the office of freshman Congressman William Cohen (R) of Maine was stamped as received on May 25, 1973. But it wasn’t discovered until a couple months later when a new chief of staff found it among a stash of unanswered mail.

The young Collins, a junior at St. Lawrence University in Canton, N.Y., expressed hope of a “government career after college.” Her parents, both politically active in her tiny hometown of Caribou, Maine, were friends with the congressman. Her inquiry led to an internship the next summer – a momentous time for the nation, for politics, and for the A student with the wire-rimmed glasses.

Collins’s boss was at the epicenter of a national controversy as a member of the House Judiciary Committee drafting articles of impeachment against a president who belonged to his own party, Richard Nixon. During the Watergate scandal, the House was controlled by Democrats. Of the 17 Republicans on the committee, only seven voted for impeachment, Mr. Cohen among them.

One of the jobs assigned to the student from Caribou was to open the mail. Instead of the usual 75 letters a day, the office was trying to answer 10,000 – many of them nasty. Some contained little stones wrapped in paper bearing the biblical quotation from Jesus: “Let him who is without sin cast the first stone.”

Cohen also received death threats. Because of his impeachment vote, he thought his brief congressional career would be over. “But of course it wasn’t,” says Collins, in her elegant private “hideaway” office in the Capitol. “People in Maine really admired his independence and his commitment to doing the right thing. And that was inspiring to me.”

Collins went on to work for Cohen for 12 years, becoming a senior aide after he was elected to the Senate in 1978. “Someone like William Cohen was the epitome of the moderate Republican,” says former Senate historian Don Ritchie. “It’s very significant that Susan Collins comes to work for him at that time.”

Cohen worked closely with even the most liberal of Democrats. He had a hands-off management style that gave his staff a lot of leeway. “I think Susan saw how we conducted ourselves, and she knew, coming from me, that I wanted her to deal with just the facts,” Cohen says. He never asked about any of his staff’s party affiliations. “All I cared about is just bring your mind to me,” Cohen says of Collins, whom he calls a “workhorse,” not a show horse.

Within a short time, Cohen made Collins his staff director on the government oversight subcommittee. It was a huge responsibility for someone so young. Cohen left it to her to decide which subjects to investigate and whom to bring as witnesses to committee hearings. “She was 26 going on 40 in terms of being responsible and on top of her game,” says Bob Tyrer, former chief of staff for Cohen and a longtime friend of Collins who once worked as her campaign manager. She goes “five levels deep” on the details.

***

Caribou is a typical small town in Maine’s struggling and vast rural stretches. Church steeples pierce the sky. A quaint, brick library anchors the main intersection. Tucked into Maine’s northeast corner, the town is surrounded by potato and broccoli fields.

The brick-fronted house where Collins grew up and where the senator’s mother, Pat, still lives sits on a hilltop in a neighborhood of modest homes with clipped lawns. Down below lies Collins Pond, the site of the former family lumber mill. Today, a modern building-supply store, S.W. Collins, has taken its place. The business has been in the family for five generations and is now run by the senator’s brothers Sam and Gregg.

It is her roots here in Caribou, say those who know her best, that have shaped who Collins is today. They trace her work ethic, pragmatism, and sense of civic duty to this close-knit community where schools closed so all the kids could harvest potatoes, Collins among them. (Machines do the work today.) Those who know her call Collins a “classic” Republican from a small town in Maine – modest, with a New England sense of frugality.

Public service is “almost a theological belief” to the senator, says Mr. Tyrer. Her mother and father each served as mayor. Collins’s father, Don, was a state senator, one of four generations of family members to serve in the state Legislature. Her mother ended up president or chair of any entity she served on, Collins says, including the University of Maine Board of Trustees. Juggling six children and a career, she ran a regimented household, with dinner promptly at 6 p.m.

“[Our parents] often said, ‘if you’re going to complain, you’ve got to earn the right to complain,’ ” says Sam Collins, from the building-supply’s corner office overlooking the pond. “I think that had an impact on all of us. If we’re going to complain, well, we’d better be prepared to serve.”

Caribou is a "caring" place, he adds. People come together when somebody is ill or dies. Sam describes his sister as similarly compassionate. She taught him how to read, and how to ride a bike, patiently wheeling him up and down the driveway. The neighborhood children clamored for her as a babysitter because they loved her entertaining stories and plays.

As a student, Collins took her studies seriously. In her senior year, she was one of only two students in Maine to be selected for a youth program in Washington. The trip made a profound impression on her.

The highlight was meeting Maine’s first woman senator, Republican Margaret Chase Smith. Unexpectedly, Senator Smith invited Collins into her private office where they talked for nearly two hours. She left feeling that women could do anything, and with a copy of the senator’s famous floor speech, her unflinching “Declaration of Conscience” decrying McCarthyism.

Collins considers her mother and Smith her female role models, even as she tries to be one to the next generation. It is one reason she frequently meets with schoolchildren, such as those in Winterport. As she likes to remind them, if someone from Caribou can grow up to be a senator, they, too, can aspire to do anything.

Yet, as Collins would find out, the journey isn’t always easy.

***

In 1994, Collins ran for governor of Maine, even though the only offices she had ever held were vice president of her condo board and president of the student council in high school. But since leaving Capitol Hill, she had gained experience on the executive side of government, working for five years in the cabinet of Maine Republican Gov. John “Jock” McKernan, and later for President George H.W. Bush’s Small Business Administration.

She didn’t like retail politics at first. Her campaign manager and current chief of staff, Steve Abbott, had to push her to approach strangers in a diner – to interrupt their meals, introduce herself, and not be put off by the disinterested stares. “Nobody, but nobody, knew who I was,” she said in a pep talk to candidates at the Maine GOP convention in May.

Doggedly, Collins won the eight-way Republican primary. But she came in a distant third in the general election, losing to Angus King, now the junior senator from Maine. The loss devastated her, but she also learned something: A party needs to unify behind its candidate after a contested election. Hers didn’t. “I did not know that I really needed to reach out to each of those candidates the very next day and call them and ask for their help.”

Collins ended her campaign broke and retreated to her rustic, yellow cottage – or “camp,” in Maine vernacular – near Sebago Lake. She took a job as director of the Center for Family Business at Husson University in Bangor.

Two years later, when Cohen announced he was retiring, she sought his seat. Her persistence in the gubernatorial race had raised her profile and generated goodwill. Still, she faced stiff head winds: She ran against two wealthy Republicans in the primary, and in the general election faced the most popular Democrat in the state, a former governor.

On election night, immediately after the polls closed, several media outlets called the race for her opponent as she and Tyrer, her campaign manager, were about to fly from Bangor to her campaign headquarters in Portland.

“We got in our little plane ... and that was a sobering piece of news to fly back to Portland with,” Tyrer says. “I just remember how determined she was. How calm she was. She said, ‘I don’t think that’s a correct conclusion.’ ” As it turned out, the reports were wrong: Collins won by 32,000 votes.

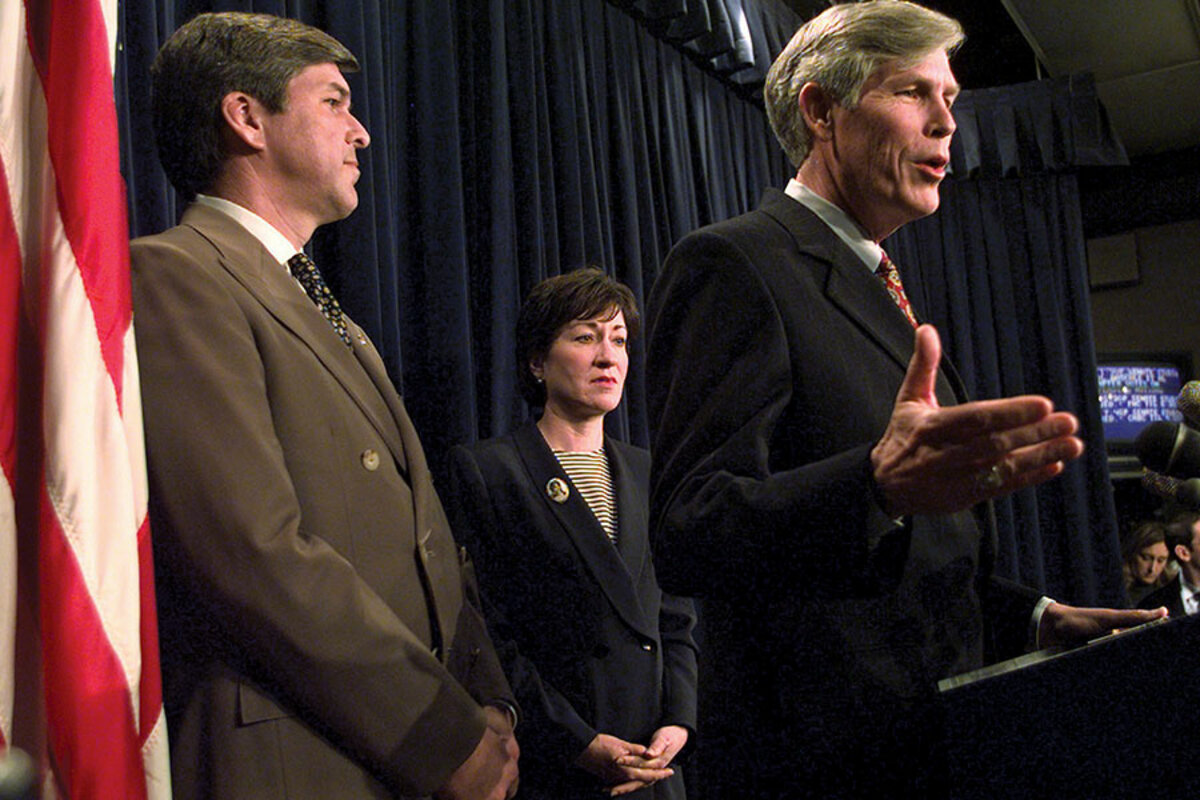

When the newly minted senator arrived in Washington in 1997, one of the first things she did was vote to confirm her former boss, Cohen, as President Clinton’s new secretary of Defense. It fit Cohen’s, and Collins’s, bipartisan approach to governing: a Republican working in a Democratic administration. But as she noticed upon arrival, the Senate had changed in the 10 years since she had worked as a Cohen staffer.

And not for the better.

***

The shift in atmosphere was partly rooted in a period of upheaval that she had gone through earlier on the Hill: Watergate. Simply put, says Mr. Ritchie, the historian, Watergate marks “the very end of the old system that existed since the Civil War” – a system in which each party was irreconcilably divided.

Under the old order, liberal Democrats in the North clashed with conservative Southern Democrats determined to protect segregation. Among Republicans, it was Eastern liberal and moderate internationalists versus those in the Midwest who staunchly opposed the New Deal and American intervention abroad.

With the parties so split internally, bipartisanship was the only way to get anything done. But civil rights legislation and Watergate pushed each party to become more ideologically homogeneous, fostering polarization between them. “You see a reshuffling of the political parties after Nixon’s resignation,” says Ritchie. “It’s a gradual evolution” that still allowed senators like Cohen to reach across the aisle.

Two decades later, another event shook Washington: the “Gingrich Revolution” of 1994. In that midterm election, then-House minority whip Newt Gingrich (R) of Georgia led his troops to take control of the House for the first time in 40 years. Republicans captured the Senate, too. Mr. Gingrich was a talented tactician, but he played “this game of politics of personal destruction,” says John Feehery, former spokesman for House Speaker Dennis Hastert (R) of Illinois, who succeeded Gingrich as speaker.

In the campaign, Gingrich united Republicans behind a GOP agenda, outlined in the “Contract with America.” The agenda turned local congressional races into a national rallying cry for control of Congress. That led to today’s “permanent campaign,” in which trying to win a majority of seats in the next election trumps problem-solving on the Hill, write Thomas Mann and Norman Ornstein in their 2012 bestseller, “It’s Even Worse Than It Looks.”

The authors argue that the fundamental cause of dysfunction in Washington is a “mismatch” between the Founding Fathers’ system of checks and balances that thrives on caution and compromise, and parties that have become ideologically uncompromising. As speaker, Gingrich found common ground with Clinton, but that was sandwiched between two government shutdowns and Clinton’s impeachment in the House.

Democrats were hardly innocent, acknowledge Mr. Mann and Mr. Ornstein. They returned tit for tat and set the stage for decades of judicial wars through their “brutal attacks” on Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork in 1987. But the authors consider Gingrich “the singular political figure” responsible for setting a more caustic tone in Congress.

“It’s baloney!” says former Gingrich spokesman Rick Tyler, about the authors’ broad indictment.

“Gingrich believed, as we all did then, that Republicans had real ideas and wanted to be in charge for a while.” Through the Contract, Gingrich did the hard work of moving the country forward by winning the argument, he says.

**

It was two years after the Gingrich Revolution that Collins won her Senate seat. The freshman was struck that first year by two things: It is much easier to advise someone how to vote than to vote yourself, and the Senate had, in fact, changed considerably.

“It wasn’t nearly as partisan as it is today, but it was more partisan than it had been 10 years before, when I left,” says Collins. “And I remember being surprised by that.”

She noticed not only a narrowing of the ideological spread within each party, but more pressure to vote the party line. The number of moderate Republicans who lunched together on Wednesdays had shrunk from about 20 to five, most of them from the Northeast.

“Susan and I got there together that year and we were welcomed, and I would even say celebrated, as moderates,” says former Sen. Mary Landrieu (D) of Louisiana. At that time, compromise was not yet a dirty word, she says.

Collins signaled her willingness early on to go against her own party. In 1999, she voted to acquit Clinton of both impeachment charges, joining only four other Republicans. She puts that as No. 1 among her most “courageous” votes, “just because I was so new, and the consequences were so high.” In 2010, she was the lone vote among her GOP colleagues on the Armed Services Committee to repeal the ban on openly gay people in the military, a change she championed.

She was also carving out a role as a problem-solver. In December 2004, Collins pushed through what she considers her greatest legislative achievement: the biggest overhaul of US intelligence in 50 years, prompted by the 9/11 attacks. Turf battles made this issue a particularly tough one, despite support from the 9/11 families.

“I thought this bill was dead 100 times,” she says, thinking back on her efforts as chair of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. She did it with an “iron fist” and “velvet glove,” says her close friend and the ranking Democrat on the committee at the time, former Sen. Joe Lieberman of Connecticut.

On the Senate floor, Collins battled a senior Republican known for a volcanic temper by reciting, in precise detail, the elements of the bill. She neutralized the staunchly opposed defense secretary by first getting buy-in on compromise language from the White House. And she presented a bipartisan front by linking arms with Senator Lieberman.

In the years since, national security issues and foreign policy have become much more difficult on the Hill. In fact Lieberman, echoing others, believes a 9/11 bill might not even pass today. “Even in this worse time, that kind of assault and attack on America hopefully would break through the partisanship ... but I can’t say with confidence the same would happen again.”

***

On a cool spring day, Collins is devoting herself to constituents – and cake. In the morning, she toured an opioid treatment center in Portland. In the afternoon she would visit a nonprofit that provides rides for seniors. After that, she would drive two hours north to Bangor, where she lives with her husband and closest adviser, Thomas Daffron. On her agenda there: Whip up a lemon-almond cake to bring to a friend’s house for dinner that night.

“I love lemon. I love almond. So I think it’ll be good,” she says during a lunch at David’s, one of her favorite restaurants in Portland.

Collins is a foodie. She loves to cook, even after a late night at the Senate. It relaxes her. But food is much more than a hobby for the senator – and, more broadly, you could argue food is important to the Senate, too. Dining together acts as a binding agent, helping to build relationships on the Hill where opportunities to socialize across party lines are far fewer than they used to be.

The hyperpartisanship in Washington today is rooted in many different causes: the election of more members from the hard-line wings of the parties, intense pressure from voters and outside groups not to compromise, news consumers drinking from a more partisan and toxic media stream.

Yet one of the most important but least-talked-about factors is the simple decline in personal relationships. Gone are the days when members of Congress lived in the Washington area, bonding over their children’s school events, golf, or at parties. Instead, they usually work an intense three days in D.C. and then travel to their home states. The lack of social interaction has led to an erosion of deep, cross-party friendships, which in turn feeds a deficit of trust – a crucial ingredient for legislating.

On their few workdays in town, senators lunch separately with their party caucuses. It’s one reason Collins and Democrat Dianne Feinstein of California are carrying on the tradition of private, bipartisan dinners for women senators every five or six weeks.

“If you break bread with someone, it’s far harder to demonize them,” says Collins. “It really is.”

The women of the Senate – a record 23 now – consider themselves a force for comity. While their ideologies may differ, they are quick to point out that they tend to work more collaboratively than their male colleagues. That’s backed up by a study from Quorum, an online public affairs platform, which found that the average female senator cosponsored 171 bills with a member from the opposite party. The average male senator cosponsored 130 bills.

“When I think about areas of civility, more often than not there is a good gathering of women that come with it,” says Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R) of Alaska, one of Collins’s closest friends in the Senate sisterhood.

Take the 16-day government shutdown of October 2013. A fight over Obama’s healthcare plan and spending had ground most of the government to a halt. Collins was in her office on a Saturday, watching floor speeches on C-SPAN. She saw a Democrat blame the other side. She saw a Republican do the same. She flipped on her computer, tapped out some points, and headed to the Senate chamber. There, she put forward a simple plan that helped end the shutdown.

The moment she got off the Senate floor, her phone started ringing. Collins considers it “significant” that the first people to call were all women. Along the way, several male senators joined in, and the bipartisan group formed the “Common Sense Coalition,” led by Collins and Sen. Joe Manchin (D) of West Virginia.

“If there’s any hope for bipartisanship for the Senate going forward, it’s going to be led by the women, because the women still talk to each other,” says Thomas Bright, a former press secretary for Cohen.

A few outlets for cross-party social interaction still exist on the Hill. When Cohen was first elected to Congress in 1972, he was advised to frequent the House gym, not for shooting hoops – he was a top basketball player in high school and college – but to make friends.

About a quarter of the Senate also attends a bipartisan prayer breakfast on Wednesday mornings. Collins frequents a more intimate, bicameral women’s prayer group. As the only senator, she relishes this time with her House friends, commenting that members of the two chambers don’t know each other well.

One year the group studied the Psalms. Being Roman Catholic she had never read much of the Bible, she says with a little laugh. Now, “I love the Psalms.” When her father died in the spring, it hit her hard. She needed a comforting reading for the funeral. “I knew to go right to Psalm 121: ‘I looked up my eyes to the hills, from whence cometh my help.’ ”

***

When Collins went against her party and voted not to repeal the ACA last year, something unusual happened. As she was going home for the weekend, entering the terminal in Bangor, people in the crowd of outgoing passengers recognized her and a few began to applaud. Soon, virtually everyone joined in. It was something she hadn’t experienced before as a senator.

Yet the reception she received from members of her own caucus was different. At the first GOP policy meeting after the vote, according to someone familiar with the session, one first-term senator suggested that all three Republicans who voted against repeal – Collins, Murkowski, and John McCain of Arizona – lose their committee chairmanships. The three were not team players. Collins explained to one of her critics that the Senate is not a football team.

The highs and lows she experienced with the health-care vote show the complexity of lawmaking in a hyperpartisan age and raise a question for Collins going forward: Is there room for a compromise-seeking senator like her in the Washington of today? Many contend that a revitalization of the “sensible center” is the key to fixing a “broken” political system.

Collins herself is optimistic that the “pendulum” will swing back toward the middle. The US has recovered from divisive periods in the past, she says. “Eventually, I think the center is going to rise up, and either we will see the parties become more inclusive again ... or we’re going to see the rise of a new party” of moderates.

But Tyrer, her longtime friend, is skeptical. The trend in both parties is for candidates to have a “sharper ideological edge,” or be self-funded, or both. He doesn’t think average voters have gotten more extreme, but activists have, and President Trump provides fuel for both sides. Indeed, the animus on both sides runs deeper than ever. Last October, a Pew Research Center study of polarization found that the shares of Republicans and Democrats who have “very unfavorable opinions” of the other party have more than doubled since 1994.

The public may cry for centrism, moderation, and bipartisanship, but it’s rarely rewarded by the voters, writes Nathan Gonzales, editor and publisher of the nonpartisan Inside Elections, in an email. At the same time, he’s skeptical that most people want compromise. “They want the other side to agree with their point of view and then call it bipartisanship.”

Collins says she’s never seen a more divisive period in American politics, including in her own home state. Red Maine is getting redder, blue Maine bluer. The senator found it “appalling” that protesters demonstrated against the tax cut outside her house for three weeks last year. They left behind trash and disrupted neighbors, she says.

But many Mainers genuinely fear for their future under Mr. Trump, and activists feel they need to take extraordinary measures. For instance, they worry they will have to pay for the $1.5 trillion tax cut – that Collins supported – with cuts to Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security. “People feel a real sense of betrayal,” says Mike Tipping, of Maine People’s Alliance, a grass-roots organizing group. “They saw her as a moderate, but that legislation was anything but.”

If Collins votes to confirm Judge Kavanaugh, it will further damage her centrist reputation, which she carefully tends and which the media lap up, says Mr. Tipping. The senator may not have voted for Trump in 2016, but she has since voted with the president nearly 80 percent of the time, according to the analytical data website FiveThirtyEight.

And yet, that is not enough to satisfy certain Republicans in Maine, including its GOP governor, Paul LePage. Often described as Maine’s Trump, he has at times sharply criticized Collins. At the state GOP convention in May, a few delegates complained privately that she is not really a conservative and too often speaks against the president. Several political observers expect her to face a primary challenge if she decides to run in 2020 – though she remains popular in the state, with a 56 percent approval rating.

“The problem is that the Republican Party has changed so dramatically around her,” says her fellow Maine senator, Mr. King, an independent with whom she is in touch almost daily. The decline of the middle, he adds, has “isolated her more and more.” Some wonder whether polarization will have to get worse before it gets better. On the Democratic side, 10 senators are up for reelection in states that Trump won – five of them in states he won by significant margins. The midterm elections will tell whether Americans want to keep these more moderate Democrats or not.

On the other hand, Democrats hope to retake the House through suburban swing and rural districts. Perhaps the opportunity for moderates is with Democrats rather than Republicans right now?

“The operative term is ‘right now,’ ” answers King. “The question is whether Democrats [first] will go through a kind of purge.”

Jennifer Duffy, of the independent Cook Political Report, shares Collins’s view that the pendulum will eventually swing back toward the center, because “what we have now is not sustainable.”

Collins believes most Americans stand in the middle politically, which is one reason she remains buoyant about the future. Indeed, last year’s Pew survey found that most Americans want political leaders to compromise. If people in the middle want to change America’s political culture, the senator argues, they need to become as “fanatical” as people on the extremes.

That fanaticism might apply to Joel Searby, a strategist with Unite America, a group promoting independent candidates. He has proposed to a few key senators that after the election a bipartisan bloc of centrists take advantage of their clout in what is sure to be a narrowly divided chamber and support a pragmatic new majority leader – say, Susan Collins if it’s a Republican majority or Michael Bennet of Colorado if Democrats win their long-shot bid.

That sounds good in theory, but it’s totally unrealistic, says Senator Manchin, as he’s driving home to West Virginia in a heavy rain. The base would turn against the leader, who would be like “a person without a country.”

In any case, Collins has no interest in a leadership position. It would mean sacrificing her freedom to vote as she sees fit. Still, asked to engage in a little blue-sky thinking, Manchin describes the Senate under a majority leader Collins: She would be very fair and guarantee civility. In short, says the senator, “It would be a gift from heaven.”