GOP squeaks by in another special election – but warning signs abound

Loading...

| WASHINGTON

Winning, of course, is always better than losing. But the narrowness of Republican Troy Balderson’s apparent victory in the special congressional election in Ohio on Tuesday suggests a “blue wave” may be heading for many suburban districts. In 2016, President Trump carried the suburban Columbus district by 11 percentage points, and yet Mr. Balderson is leading by less than 1 percent, with provisional and absentee ballots still being counted. It’s true that the first midterm elections of any presidency almost always produce a partisan backlash. Democrats under President Barack Obama got “shellacked” – his word – in 2010. This year, Republicans are running under a controversial president who’s generating a severe gender gap, with suburban college-educated women increasingly wary. “There’s no question that there’s been shrinkage in the party in urban and suburban areas,” says Doug Preisse, the GOP chair in Ohio’s Franklin County. “I did get lifelong Republicans in the district ... letting me know that the president’s visit caused them to shy away from voting for Troy. But I also witnessed people being reminded of the importance of the race, and deciding to turn out.”

Why We Wrote This

In Ohio’s 12th Congressional District Tuesday, suburban voters, particularly women, moved further away from the GOP. The trend is forcing Republicans to rely more on rural, blue-collar turnout – a narrower path to victory.

Republicans are cheering their likely victory in Tuesday’s special election to fill an open House seat in Ohio. Winning, of course, is always better than losing. But in the Republican corridors of power, both in the Buckeye State and in Washington, the cries of joy are muffled.

The narrowness of state Sen. Troy Balderson’s apparent victory suggests a “blue wave” may be heading right for suburban districts currently held by Republicans – where GOP women, in particular, are increasingly wary of President Trump. And even if Mr. Balderson keeps Ohio’s 12th Congressional District in the Republican column, other districts with less of a GOP tilt could flip.

In 2016, Mr. Trump carried the suburban Columbus district by 11 percentage points, and yet Balderson is leading by less than 1 percent, with provisional and absentee ballots still being counted. This narrow margin continues the trend of Republicans underperforming significantly in special House and Senate elections since Trump took office.

Why We Wrote This

In Ohio’s 12th Congressional District Tuesday, suburban voters, particularly women, moved further away from the GOP. The trend is forcing Republicans to rely more on rural, blue-collar turnout – a narrower path to victory.

“There’s no question that there’s been shrinkage in the party in urban and suburban areas,” says Doug Preisse, chairman of the Republican Party in Ohio’s Franklin County, part of which falls in the 12th district.

Some of the challenge for Republicans lies in running under a controversial president, particularly one facing a severe gender gap – 12 points, according to Gallup nationwide polling. Millennial women are an especially tough sell for Trump; 70 percent now identify as or lean Democrat.

It’s true that the first midterm elections of any presidency almost always produce a partisan backlash. Democrats under President Barack Obama got “shellacked” – his word – in 2010.

Still, Mr. Preisse calls the closeness of the Ohio-12 race a “canary in the coal mine” in the run-up to Nov. 6, when every House seat will be on the ballot as well as a third of the Senate.

“If Balderson had lost, then there would be a turkey-sized canary in the coal mine,” Preisse says. But a close victory signals a regular-sized canary, and “it will keep chirping till November.” This was the last special election before the midterms, and the candidates will go head-to-head again in November.

Turnout and the Trump factor

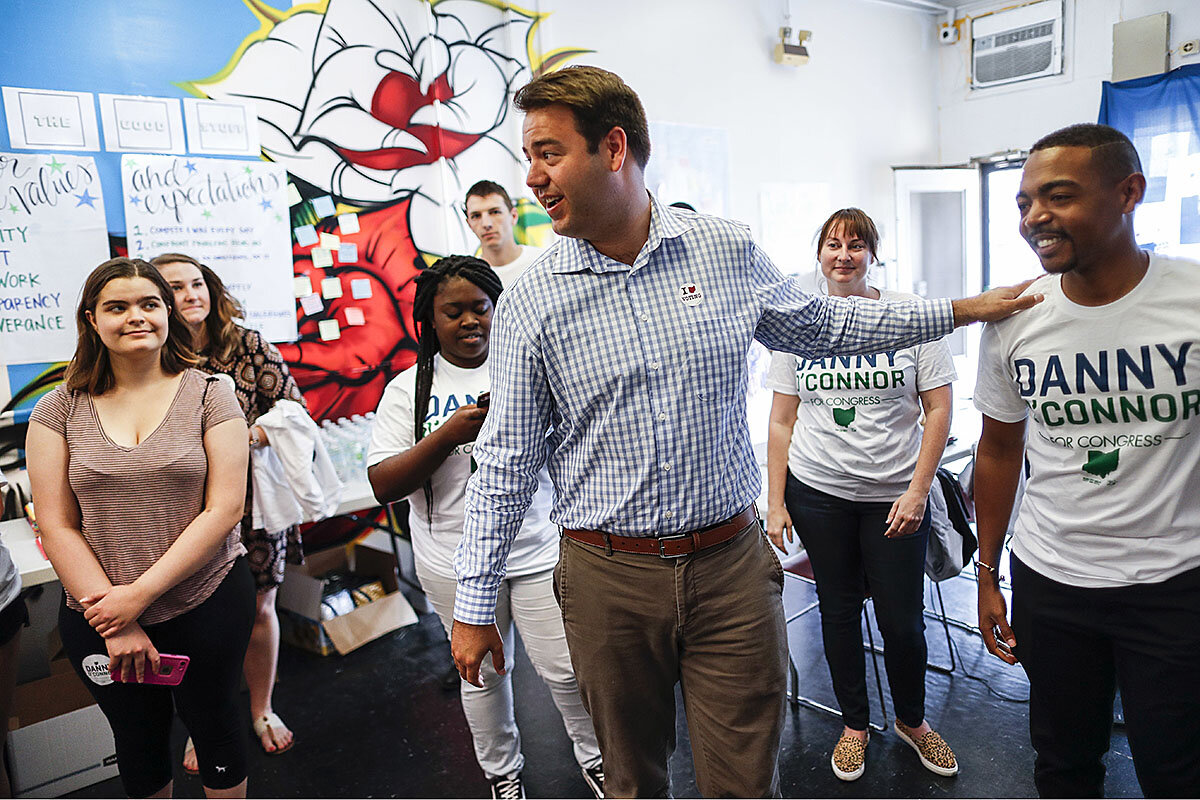

On Tuesday, turnout was the name of the game. In Franklin County, which covers Columbus, turnout was larger than in the district’s other counties – almost handing the election to Democrat Danny O’Connor, a popular local official.

The timing also mattered: It’s August, and a lot of voters are out of town.

“Democrats used early voting to get their vote out over a month, while the Republicans vote on Election Day,” says Jay O’Callaghan, a former US House GOP staffer.

Preisse expects a more traditional turnout in November, with more people voting, and predicts Balderson will probably win again. But there are plenty of other districts available for Democrats to flip. To retake the House, they need a net gain of 23 seats; the GOP is defending 72 districts that have less of a Republican tilt than Ohio-12.

The Trump factor bears watching, but how that nets out is hard to gauge. Did Trump’s last-minute rally in Delaware County spur his supporters to turn out, or did it inspire anti-Trump voters? Preisse says it likely cut both ways.

“I did get lifelong Republicans in the district – not only from Franklin County but also Delaware County – letting me know that the president’s visit caused them to shy away from voting for Troy,” says the Franklin County chairman. “But I also witnessed people being reminded [by Trump] of the importance of the race, and deciding to turn out.”

Another key figure may also have had an impact: Ohio’s Republican governor, John Kasich. He’s a frequent Trump critic, and has hinted at a primary challenge in 2020, but on this issue – the need to keep Governor Kasich’s former House seat in GOP hands – they agreed.

The mild-mannered, mainstream Balderson, in fact, is hardly a Trumpian figure, and getting the stamp of approval from Kasich, also a mainstream Republican, perhaps helped buffer any negative fallout from Trump’s touch.

Big Labor wins big

For Democrats, the best news of Tuesday night came in Missouri, where the labor movement defeated a “right to work” measure that would have dealt a major blow to unions. The referendum asked voters to affirm or reject a new state law barring mandatory payment of union dues by workers. Voters defeated the measure 67 percent to 33 percent, making Missouri the first state to turn back a “right to work” law in decades.

“We thought we might win by 10 or 15 percent,” says Julie Greene, mobilization director at the AFL-CIO, the nation’s largest federation of unions. The big margin “was really just a testament to the [outreach] program.”

National labor forces allied with Missouri’s unions to reach out to workers at their jobs and via phone-banks, door-to-door, mail, and online. The key was to start early, take nothing for granted, and reach far and wide, not just to union members and families, says Ms. Greene.

“Unionization hits at kitchen-table issues, which affects many more than just union members,” she says.

Labor’s political operations are focused, too, on the midterms – and were on the ground in Ohio’s 12th district, as they were last March in a special House election in Pennsylvania, where Democrat Conor Lamb won in an upset. Most, but not all, labor endorsees are Democrats.

At a Monitor Breakfast last Wednesday, AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka spoke of labor’s early start in mobilizing this election cycle. Normally, he said, door-knocking and phone banks start after Labor Day. This year, they started June 1.

“This is going to be the biggest, deepest member-to-member program that we’ve ever had,” Mr. Trumka said.