Is our political divide, at heart, really all about abortion?

| Washington

When Kristen Day joined the nonprofit Democrats for Life of America in 2002, she wanted only to be put out of business.

A new mom at the time, she had dreamed of a day when abortion would become a nonpartisan issue; when people who called themselves “pro-life” could support the cause regardless of whether they identified as Democrat or Republican; when a lawmaker’s career would no longer hinge on how he or she voted on an abortion bill. She says she believed that moment was near.

“I was so naive,” Ms. Day says in a phone interview.

In the years since, as the two political parties have doubled down on ideological purity, liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats have essentially become oxymorons. The partisan divide has grown into a chasm.

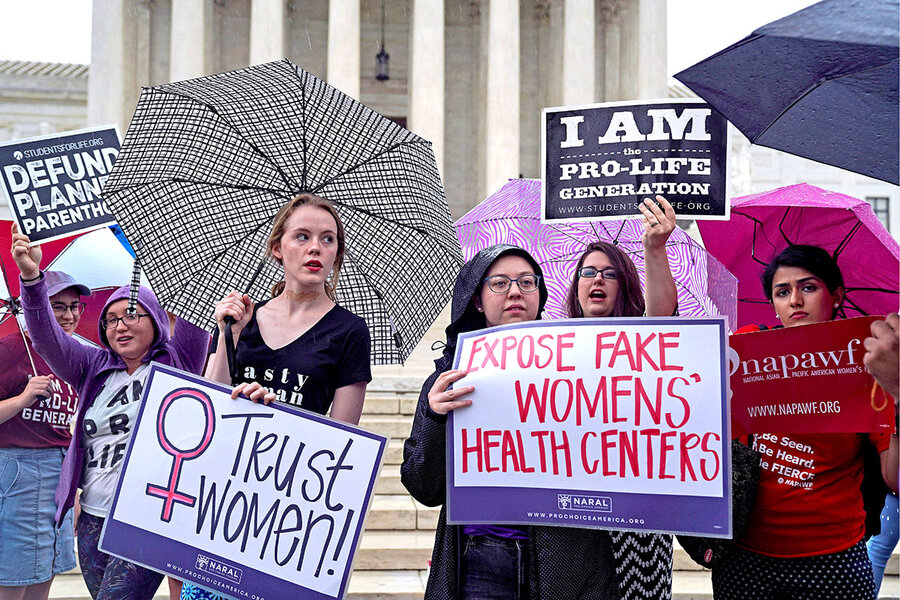

And abortion is often the issue that most sharply cuts in between. Each party has used abortion – with its intensely personal, life-and-death stakes – to motivate voters. If you believe that abortion is murder, how could you ever vote for a Democrat? If you believe it’s not, and think that banning it would deny women control over their own bodies, how could you cast a ballot for a Republican?

Folks like Ms. Day now find themselves shunned by activists on both sides. Attitudes toward abortion, perhaps more than ever, are directly and indirectly shaping the highest reaches of United States politics.

The 2016 election, for instance, turned on factors such as public frustration with politics as usual, the investigation into Hillary Clinton’s emails, and the maturing of social media as a tool for political messaging.

But exit polls also showed that among voters who said that the Supreme Court was the most important basis for their decision, nearly two-thirds voted for Donald Trump. That included evangelical Christians, many of whom were willing to put aside concerns about the president’s personal life in pursuit of the repeal of Roe v. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court ruling that legalized abortion.

“You can make the argument that a nontrivial reason that Donald Trump is president is because of abortion,” says Mary Ziegler, a law professor at Florida State University who specializes in family, sexuality, and the legal history of reproduction. “Some voters saw a Supreme Court vacancy, and they held their noses and voted for Trump.”

That’s a direct example of abortion’s political impact. But a more intriguing question may be this: If abortion had never become the wedge issue it is today, would our political landscape look anything like it currently does?

A medical – not political – issue

Abortion wasn’t always viewed through a political lens. When it first surfaced as a subject of public debate in the mid-19th century, it was against the backdrop of the medical industry’s effort to professionalize itself – and chip away at midwives’ authority in the process, says Karissa Haugeberg, an assistant professor of history at Tulane University in New Orleans. Then, as the century turned and new immigrants began streaming into the country, concerns over abortion began to center around the declining birthrate among white Americans.

But the issue, while polarizing, was not partisan.

“Even in the 1940s and ’50s, it would have seemed strange to ask someone running for president what their view on abortion was,” says Professor Haugeberg, who traces the history of abortion opponents in her 2017 book, “Women against Abortion: Inside the Largest Moral Reform Movement of the Twentieth Century.”

Some of the earliest supporters of modern abortion rights were Republican women like Constance Cook, the state assemblywoman who co-wrote the bill that legalized abortion in New York three years before the Roe ruling. Catholic Democrats, meanwhile, were early opponents of abortion; among the holdouts against pre-Roe legalization were heavily Catholic states like Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that the parties began to realign according to abortion. The GOP, in an effort to win new voters, backed abortion opponents like televangelist Jerry Falwell and his Moral Majority in their bid to pass a constitutional amendment banning abortion. When the proposal failed in 1983, the two groups, instead of ending their partnership, settled on a new one: the quest for a reconfigured Supreme Court that could undo Roe.

By 1987, abortion had become the kind of issue that could make or break a Supreme Court nomination, as in the case of failed nominee Robert Bork. By 1992, Democrats were barring abortion-rights opponents like Pennsylvania Gov. Bob Casey Sr. from speaking at the national convention. By 2010, opposition to abortion was driving the tea party revolution, as conservative Republicans picked off congressional Democrats who opposed abortion rights but had voted in support of the Affordable Care Act.

There’s a reason that Democrats for Life endorses only three U.S. senators today, down from about 40 in the late 1990s. It’s the same reason that only two Republicans in the chamber still publicly support abortion rights.

The confirmation of conservative Justice Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court last fall only raised the stakes.

Anticipating that Roe may soon be overturned, abortion-rights activists have doubled down on their support for choice. At their urging, Democratic-controlled states like Virginia and New York have passed some of the country’s most expansive abortion-rights laws to date.

Opponents of abortion, who have been at the forefront of state-level restrictions for years, have pressed for the opposite from GOP state lawmakers. Republicans now are not only working to send a case to the high court that could lead to Roe’s repeal, but also preparing to make abortion illegal in certain jurisdictions as soon as the ruling is overturned. On Tuesday, the Senate Judiciary Committee held a hearing on the “Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act,” which would place a federal ban on abortion at 20 weeks, with some exceptions.

It’s a situation ripe for even more ugliness and division – just in time for the 2020 presidential campaign.

“The abortion issue has been an indicator of a larger symptom of our politics of the last 40 years,” says Daniel Williams, a history professor at the University of West Georgia and author of “Defenders of the Unborn: The Pro-Life Movement before Roe v. Wade.” “As long as both sides see it as an inalienable human right, it’s going to be very difficult to find middle ground.”

Nuanced views

The irony is that for decades, polling has found that most Americans don’t see themselves as strictly on one side or the other of the abortion debate. Gallup’s survey data going back to 1975 shows that, on average, about half of Americans think abortion should be legal under some circumstances. Only a quarter say the procedure should be legal under all circumstances, and just under 18 percent say it should be illegal without exception.

Tucked within those figures is even more nuance. Most people are willing to consider factors like whether or not the mother’s life is at risk, how long she’s been pregnant, or if sexual violence was involved.

“There’s this whole range of positions one can have, to the point where the life/choice binary just makes no sense,” says Charles Camosy, an associate professor of ethics at Fordham University and author of “Beyond the Abortion Wars: A Way Forward for a New Generation.”

But when asked to identify as either “pro-choice” or “pro-life” – the most common terms used to frame the debate – Americans split down the middle, at 48 percent each, according to Gallup. The divide is even more stark when political parties are taken into account. Of those who identify as or lean Republican, 69 percent say they are “pro-life” and 29 percent say they are “pro-choice.” The numbers flip among Democrats and those who lean Democratic.

One reason is that binaries – choice versus life, liberal versus conservative, us versus them – work well in both media and politics. A group that can quickly identify its enemy is much easier to mobilize come Election Day. Political candidates love voters who can be convinced on the basis of a single issue, just as the media loves covering conflict – especially if it makes a good headline.

Take the Roe decision, says Professor Ziegler at Florida State. “The pro-life goal is to get rid of Roe, and the choice goal is to save it. It’s easy to understand. It’s easier to generate soundbites and ads. It’s easier to explain to voters who don’t want to think about politics all the time.”

Still, abortion wouldn’t be so politically expedient if a small but vocal group of people didn’t actually feel so strongly about it. To the most ardent supporters of abortion rights, what’s at stake is women’s autonomy and freedom and power over their own bodies.

It’s hard to imagine a more important value than that, Professor Camosy says, “except maybe the very right to life of the most vulnerable.”

“So you have these two wildly important values, at least seemingly in conflict: the well-being of women and the well-being of babies,” he says. “Who wouldn’t be motivated by that?”

The link to partisanship

As the parties have diverged, political scientists have found that party affiliation – and the social identity associated with it – is increasingly the top indicator of how a person will vote in any election. That is, voters will often take their party’s position on an issue as opposed to looking substantively at an issue to decide which party suits them best. Very few things have the force to push a voter from one party to another.

But abortion might be one of them. A 2008 study in the journal Political Research Quarterly found that while defections were uncommon, when all else was equal, a “pro-life” Democrat was more than twice as likely to switch parties than the average. A “pro-choice” Republican, over time, was three times as likely to re-identify as a Democrat, the researchers found. “[I]t is difficult to think of many other issues that would rival [abortion] in the capacity to influence partisanship,” they wrote.

Another study, done in 2015 by a pair of scholars for the Centre for Economic Research in London, reported similar findings – and added that once a person had switched parties, his or her other political views often followed suit.

Studies like these raise provocative questions about the extent to which partisanship, and voters’ subsequent political views on a range of issues, might be grounded in beliefs about abortion. Which leads some to ask: Were that not the case, would we be as sharply divided as we are today?

“If it weren’t the deciding issue, people might be freer to think about a variety of issues,” Professor Ziegler says. “It wouldn’t be so coherently about the feminist vote or the religious right, because those people would be breaking down in a much finer-grained way.”

The idea – among some political scientists, anyway – is that if we are to move past the gridlock of partisan polarization, this is the culture war issue we most need to get beyond. It’s the narratives surrounding abortion that are driven by the most extreme elements on each side and where the political discourse is most out of sync with broad public opinion. Tellingly, we don’t even have a shared language or set of facts with which to talk about the experience.

“What happens in pregnancy is so different than anything else that happens in human existence,” says Rebecca Todd Peters, a religious studies professor at Elon University in North Carolina. “If we want to address the public health issues around unplanned pregnancies, we have to diagnose the problem differently.”

One word that frequently comes up in discussions about how to move forward is empathy – for the activists on both sides who are fighting for values they feel are fundamental to humanity, but even more for the women: those who gave up their babies for adoption, those who are raising children they can’t properly care for, and those who chose to end their pregnancies.

Ms. Day at Democrats for Life, who’s spent 17 years trying to end abortion in the U.S., says there’s no reason to shame women who’ve had abortions or punish them for something they can’t change.

“It’s scary when you get pregnant. A lot of times they need healing,” she says. “We need to support women, whatever decision they choose.”