As Democratic race heats up, candidates turn on each other

Loading...

| Las Vegas

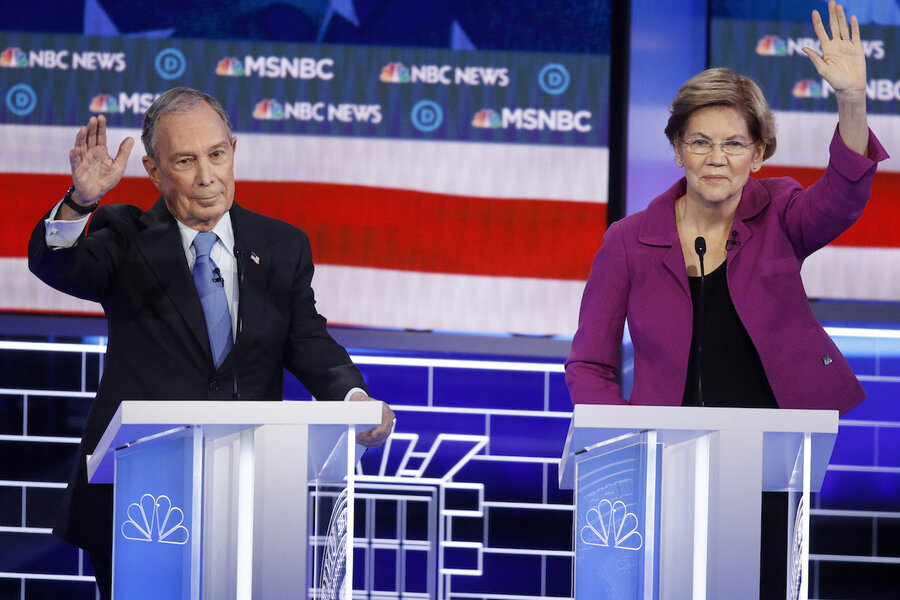

From the opening bell, Democrats savaged New York billionaire Mike Bloomberg and raised pointed questions about Bernie Sanders' take-no-prisoners politics during a contentious debate Wednesday night that threatened to further muddy the party's urgent quest to defeat President Donald Trump.

Mr. Bloomberg, the former New York mayor who was once a Republican, was forced to defend his record and past comments related to race, gender, and his personal wealth in an occasionally rocky debate stage debut. Mr. Sanders, meanwhile, tried to beat back pointed questions about his embrace of democratic socialism and his health following a heart attack last year.

The ninth debate of this cycle featured the most aggressive sustained period of infighting in the Democrats’ yearlong search for a presidential nominee. The tension reflected growing anxiety among candidates and party leaders that the nomination fight could yield a candidate who will struggle to build a winning coalition in November to beat Mr. Trump.

The campaign is about to quickly intensify. Nevada votes on Saturday and South Carolina follows on Feb. 29. More than a dozen states host Super Tuesday contests in less than two weeks with about one-third of the delegates needed to win the nomination at stake.

Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren was in a fight for survival and stood out with repeated attacks on Mr. Bloomberg. She sought to undermine him with core Democratic voters who are uncomfortable with his vast wealth, his offensive remarks about policing of minorities, and demeaning comments about women, including those who worked at his company.

Ms. Warren labeled Mr. Bloomberg "a billionaire who calls people fat broads and horse-faced lesbians."

She wasn’t alone.

Mr. Sanders lashed out at Mr. Bloomberg's policing policies as New York City mayor that Mr. Sanders said targeted "African American and Latinos in an outrageous way."

And former Vice President Joe Biden charged that Mr. Bloomberg’s "stop-and-frisk" policy ended up "throwing 5 million black men up against the wall."

Watching during his Western campaign swing, Mr. Trump joined the Mr. Bloomberg pile on. "Mini Mike Bloomberg’s debate performance tonight was perhaps the worst in the history of debates, and there have been some really bad ones," Mr. Trump tweeted. "He was stumbling, bumbling, and grossly incompetent. If this doesn’t knock him out of the race, nothing will. Not so easy to do what I did!"

After the debate, Ms. Warren told reporters: "I have no doubt that Michael Bloomberg is reaching in his pocket right now, and spending another hundred million dollars to try to erase every American's memory about what happened on the debate stage."

On a night that threatened to tarnish the shine of his carefully constructed TV-ad image, Mr. Bloomberg faltered when attacked on issues related to race and gender. But he was firm and unapologetic about his wealth and how he has used it to affect change important to Democrats. He took particular aim at Mr. Sanders and his self-description as a democratic socialist.

"I don’t think there's any chance of the senator beating Donald Trump," Mr. Bloomberg declared before noting Mr. Sanders' rising wealth. "The best known socialist in the country happens to be a millionaire with three houses!"

Mr. Sanders defended owning multiple houses, noting he has one in Washington, where he works, and two in Vermont, the state he represents in the Senate.

While Mr. Bloomberg was the shiny new object Wednesday, the debate also marked a major test for Mr. Sanders, who is emerging as the front-runner in the Democrats’ nomination fight, whether his party’s establishment likes it or not. A growing group of donors, elected officials, and political operatives fear that Mr. Sanders’ uncompromising progressive politics could be a disaster in the general election against Mr. Trump, yet they’ve struggled to coalesce behind a single moderate alternative.

Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend, Indiana, went after both Mr. Bloomberg and Mr. Sanders, warning that one threatened to "burn down" the Democratic Party and the other was trying to buy it.

He called them "the two most polarizing figures on this stage," with little chance of defeating Mr. Trump or helping congressional Democrats in contests with Republicans.

Mr. Bloomberg and Mr. Sanders were prime targets, but the stakes were no less dire for the other four candidates on stage.

Longtime establishment favorite Mr. Biden, a two-term vice president, desperately needed to breathe new life into his flailing campaign, which entered the night at the bottom of a moderate muddle behind Mr. Buttigieg and Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar. And after a bad finish last week in New Hampshire, Ms. Warren was fighting to resurrect her stalled White House bid.

A Warren campaign aide said on Twitter that her fiery first hour of debate was her best hour of fundraising "to date."

The other leading progressive in the race, Mr. Sanders came under attack from Mr. Biden and Mr. Bloomberg for his embrace of democratic socialism.

Mr. Sanders, as he has repeatedly over the last year, defended the cost of his signature "Medicare for All" healthcare plan, which would eliminate the private insurance industry in favor of a government-backed healthcare system that would cover all Americans.

"When you asked Bernie how much it cost last time he said ...'We'll find out,'" Mr. Biden quipped. "It costs over $35 trillion, let's get real."

And ongoing animosity flared between Mr. Buttigieg and Ms. Klobuchar when the former Indiana mayor slammed the three-term Minnesota senator for failing to answer questions in a recent interview about Mexican policy and forgetting the name of the Mexican president.

Mr. Buttigieg noted that she's on a committee that oversees trade issues in Mexico and she "was not able to speak to literally the first thing about the politics of the country."

She shot back: "Are you trying to say I'm dumb? Are you mocking me here?"

Later in the night she lashed out at Mr. Buttigieg again: "I wish everyone else was as perfect as you, Pete."

The debate closed with a question about the possibility that Democrats remain divided deep into the primary season with a final resolution coming during a contested national convention in July.

Asked if the candidate with the most delegates should be the nominee – even if he or she is short of a delegate majority, almost every candidate suggested that the convention process should "work its way out," as Mr. Biden put it.

Mr. Sanders, who helped force changes to the nomination process this year and hopes to take a significant delegate lead in the coming weeks, was the only exception.

"The person who has the most votes should become the nominee," he said.

This story was reported by The Associated Press. Steve Peoples and Alexandra Jaffe reported from Washington. AP writer Kathleen Ronayne in Sacramento, California, contributed to this report.