Trump wants states to overturn results. Michigan was the first test.

Loading...

After largely striking out in its lawsuits alleging election irregularities amid a spike in mail-in voting this year, the Trump campaign is now focusing on trying to delay or block certification of results in key battleground states, beginning with Michigan.

Joe Biden won the state by a margin of 154,188 votes, according to approved tallies in Michigan’s 83 counties, which were certified by the state Board of Canvassers today. President Trump reportedly called Republican election officials last week, and hosted the GOP leaders of Michigan’s state Legislature in Washington in what legal scholars describe as an unprecedented effort by an incumbent president to influence the electoral process.

Why We Wrote This

A once-routine process has taken on heightened significance as the Trump campaign pursues a last-ditch effort to overturn the election by blocking certification of results in key states.

Meanwhile, Pennsylvania Republicans have sued to block certification of election results, which the state’s counties are required to provide today followed by Democratic Secretary of State Kathy Boockvar’s certification.

If Mr. Biden is certified the winner in Michigan and Pennsylvania by Dec. 8, Mr. Trump would not be able to win even if Arizona, Nevada, and Wisconsin, all of which have been called for Mr. Biden, were decided in the president’s favor.

“[Trump and his campaign] are pretty quickly running out of cards to play,” says Keith Whittington, a professor of politics at Princeton University.

The Trump campaign has turned its focus on trying to delay or block certification of results in key battleground states, after largely striking out in its lawsuits alleging election irregularities amid a spike in mail-in voting this year.

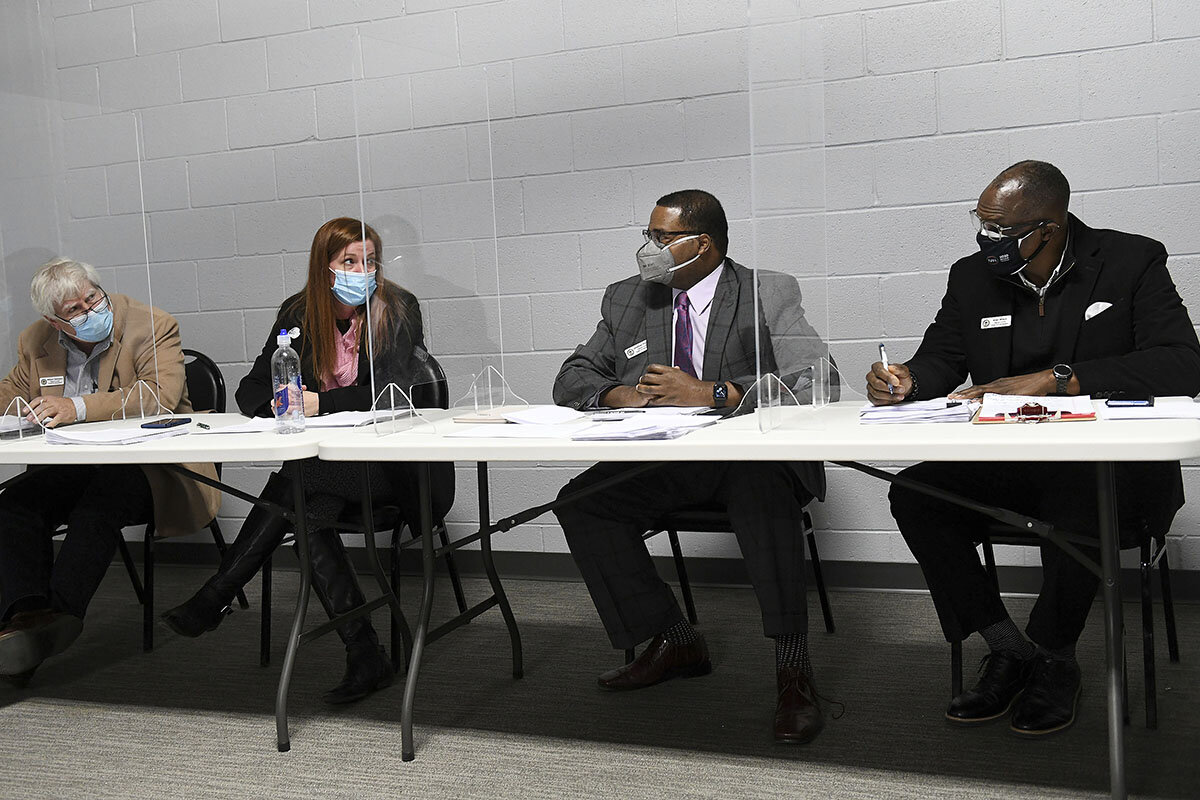

The first deadline came today in Michigan, where the bipartisan State Board of Canvassers certified election results after a week of partisan tension and state lawmakers’ trip to the White House. Joe Biden won the state by a margin of 154,188 votes.

Republicans in the state, including Republican National Committee chairwoman Ronna McDaniel, had urged a 14-day delay, citing irregularities based in substantial part on an affidavit that a judge had determined was not credible.

Why We Wrote This

A once-routine process has taken on heightened significance as the Trump campaign pursues a last-ditch effort to overturn the election by blocking certification of results in key states.

Norman Shinkle, one of two Republicans on the four-member Board of Canvassers and a Trump supporter who sang the national anthem at one of the president’s rallies last month, had indicated in advance he might vote to delay certification.

President Donald Trump’s outreach to Michigan election officials and lawmakers raised concerns of improper pressure and put a spotlight on what would normally be an obscure, routine meeting. This weekend he tweeted, "Hopefully the Courts and/or Legislatures will have ... the COURAGE to do what has to be done to maintain the integrity of our Elections,” a reference to the role state legislatures could theoretically play in overturning their state’s results.

Legal scholars describe Mr. Trump’s actions as an unprecedented effort by an incumbent president to influence the electoral process. In two other disputed elections – the election of 1800, when Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr tied, and 1876, when Samuel Tilden won the popular vote but Congress intervened and declared Rutherford B. Hayes the winner amid widespread intimidation of African American voters in the South – the incumbent at the time (John Adams and Ulysses S. Grant, respectively) did not intervene on behalf of one side.

“To my knowledge, there is no historical precedent for the current moment,” says Edward Foley, a constitutional law professor at Ohio State University, who laid out a 2020 disputed election scenario in a Loyola University Chicago Law Journal article last winter, in which he envisioned President Trump attempting to press a Republican-controlled Congress to decide the election in his favor, similar to the Hayes-Tilden election.

The margins of Mr. Biden’s victory are so significant that Professor Foley now thinks it’s highly unlikely such a scenario will take place, but he admits Mr. Trump has gotten more “running room” than he thought would be possible with such numbers. “I’m still surprised at how semi-successful, if you will, he is in making this sort of seem like Hayes-Tilden when it’s not as close,” he says.

More than 32,000 people logged into Monday’s livestream of the Michigan state canvassing board, and hundreds of people submitted a request ahead of time to speak. Among them were numerous election clerks imploring the board to certify the results. They said they and their staffs had worked long hours for months to hold a successful election amid a pandemic.

“To be in this position is definitely putting our democracy to the test,” says Tammy Patrick, who worked for 11 years in the elections department of Arizona’s Maricopa County and now serves as senior adviser to the elections team at the Democracy Fund in Washington, D.C. “We knew that it would be tested in a global pandemic, but most people expected the test would be in voter turnout and participation – not whether their validly cast votes would be considered legitimate.”

After several hours of discussion, the four-member Michigan State Board of Canvassers voted 3-0 to certify the election, with Mr. Shinkle abstaining. Meanwhile, Pennsylvania Republicans have sued to block certification of their election results, which the state’s counties were required to provide today, followed by Democratic Secretary of State Kathy Boockvar’s certification in the coming days.

The plaintiffs argued that the state legislature’s move to dramatically expand absentee voting contravened the state constitution and resulted in illegal votes. If such votes could not be tossed out prior to certification, they recommended that the GOP-run state legislature should select Pennsylvania’s electors – a scenario Mr. Trump has been talking about since September, which could potentially circumvent the popular will.

With a more than 80,000-vote margin of victory for Mr. Biden in Pennsylvania, such a scenario is seen as unlikely to succeed.

If Mr. Biden is certified the winner in Michigan and Pennsylvania by Dec. 8 and the Electoral College electors reflect the popular vote in their respective states, Mr. Trump would not be able to win even if Arizona, Nevada, and Wisconsin, all of which have been called for Mr. Biden, were decided in the president’s favor.

“[Trump and his campaign] are pretty quickly running out of cards to play,” says Keith Whittington, a professor of politics at Princeton University. Their litigation “has been so fruitless, and thrown out of court so easily, it really tears away any fig leaf for further delaying the process.”

All eyes on Wayne County

The push to delay certification in Michigan revolved largely around Wayne County, which includes the predominantly Black city of Detroit.

Republican Senate candidate John James, an African American combat veteran who lost to Democratic Sen. Gary Peters by some 93,000 votes, alleged that about 70% of Detroit’s absentee counting boards were out of balance – meaning the number of votes counted didn’t match the number of ballots cast. The filing says this affected “roughly 400 votes out of nearly 250,000 cast” and cited an affidavit from an IT contractor that a judge determined was “not credible.”

The Voter Protection Program said only 28% of Detroit’s total precincts were unbalanced – about half the rate seen in 2016 – and said the total number of votes affected was about 450 out of 872,469 – or about .05 percent of Wayne County’s total vote.

In a marathon meeting last week, the Republicans on Wayne County’s board of canvassers first voted not to certify the results, but then relented when, after being berated during a public comment session as racist, a Democratic member of the board offered support for an audit in exchange for them voting to certify. They agreed, but the following day signed affidavits seeking to restore their “no” votes, saying their trust had been breached. (This is not possible under Michigan state law.)

President Trump reportedly called at least one of the Republican members of the Wayne County board of canvassers after last week’s meeting – Monica Palmer, who said she and her family had received threats and described the president’s call as expressing concern for her security. On Friday, Mr. Trump hosted the GOP leaders of Michigan’s state legislature in Washington.

In a Nov. 21 letter, Ms. McDaniel, the RNC chairwoman, and Michigan state GOP chairwoman Laura Cox had requested a 14-day delay for an audit, arguing that step would allow "all Michiganders to have confidence in the results."

Michigan state officials and legal experts say state law requires the Board of Canvassers to certify before an audit can take place. They note that the board serves in a “ministerial” capacity, meaning it is required by law to certify the election according to the votes certified by counties, and has no investigative powers. An 1887 Michigan court ruling held that the board was not a judicial or quasi judicial body and did not have any means or right to “inquire beyond the returns of the local election boards.”

The wild card in Michigan’s state Board of Canvassers meeting today was Republican member Aaron Van Langevelde, an attorney who works for the GOP caucus in the statehouse. House Speaker Lee Chatfield rattled many Democrats when he told Fox News after coming back from the White House this weekend that if the board delayed certification, it could set off a series of events that could end with GOP legislators appointing a rival slate of electors instead of those who would honor the vote. With Mr. Shinkle having weighed in against certification, all eyes were on Mr. Van Langevelde.

Early in the meeting, he asked Christopher Thomas, a senior adviser to the Detroit elections staff who is widely respected, to confirm that the board is not a court and does not wield judicial power. Mr. Thomas confirmed that characterization, stating unequivocally that the board had no standing to decide legal or constitutional questions. Some speculated that the young GOP member was seeking cover for certifying the result amid the unusual political pressure.

“I cannot remember another example of any election where there was ... partisan strong-arming of officials in the certification process,” says Ms. Patrick, who worked as a federal compliance officer for Arizona’s Maricopa County Elections Department.

Between now and Dec. 1, three additional battleground states must certify their results: Arizona, Nevada, and Wisconsin. If any state misses the Dec. 8 “safe harbor” deadline for certifying their results, that could potentially jeopardize their slate of electors.

Election officials take oath seriously

But Ms. Patrick says she doesn’t think Mr. Trump’s pressure campaign will work, in part because every election official has taken an oath to uphold the Constitution of the United States.

“It’s important for readers to know that the vast majority of individuals who swear that oath believe in it and will strongly defend it,” she says. “Anybody that puts party or personality before country or that oath is a real problem. I think that is at the heart of what will be an issue for our country moving forward.”

On Jan. 6, Vice President Mike Pence, in his capacity as president of the Senate, will receive each elector’s vote for president. If GOP-run state legislatures were to submit a rival slate, it would fall to Congress to determine which one to accept.

Rick Esenberg, a constitutional law scholar and founder of the The Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty, a conservative public interest law firm, says he doesn’t see any basis for Republican legislators to make such a move. Speaking of Wisconsin legislators, he says, “They’re not going to vote to disenfranchise the entire state. And even if they did vote to do that, the [Democratic] governor isn’t going to go along with that.”

He says the current legal challenges and political maneuvers are “a side show” and will be over soon, brushing off concerns that this could inflict long-lasting damage to the country.

“The American republic is made of sterner stuff,” he says.