A union at Amazon? Why workers in Alabama hold the key.

Loading...

| Bessemer, Ala.

The South is known for laws more friendly to management than to organized labor. And in the small city of Bessemer, Alabama, a struggling economy has made many residents eager for just about any kind of job they can get.

Yet now a nondescript intersection along Powder Plant Road here has become the epicenter of a tumultuous contest over the power of workers. If BHM1’s almost 5,800 workers vote to unionize, in balloting that ends March 29, it could reinvigorate a long-declining labor movement in the United States and potentially begin a domino effect across Amazon’s other facilities – redefining what it means to work for the country’s second largest employer.

Why We Wrote This

In the South and in need of jobs, Bessemer, Alabama, may seem an unlikely place for a showdown between Amazon and union advocates. But its past history and present struggles have driven the moment – and attracted national attention.

One reason is that this region near Birmingham has a history at the intersection of civil rights and organized labor.

Bessemer itself was long home to a major steel mill, until 3,500 unionized employees were laid off when it closed in the 1980s. “I was born in ’64, right in the heat of civil rights. Older people would say, ‘We won here in Birmingham,’ and I’d say, ‘Won what?’” says Vincent Davis, a custodian at the Amazon site. “But we are a city of drastic change. We make others change even if we don’t change ourselves.”

This small Alabama city may not seem like the place for a labor revolution.

The South, after all, has traditionally been more anti-union than other parts of the country. And a struggling economy could make residents of Bessemer eager for just about any kind of job they can get.

Recently ranked Alabama’s “worst city to live in” (and the sixth worst nationally), Bessemer is one of the country’s poorest cities. Less than 15 miles south of Birmingham, Bessemer’s downtown is a sea of cracked concrete, with derelict hotels and empty storefronts interspersed with used car and tire stores advertising “No Credit Needed.”

Why We Wrote This

In the South and in need of jobs, Bessemer, Alabama, may seem an unlikely place for a showdown between Amazon and union advocates. But its past history and present struggles have driven the moment – and attracted national attention.

Yet after Amazon opened a warehouse here one year ago, with the promise of almost 6,000 jobs starting at $15.30 an hour, more than double Alabama’s minimum wage, what seemed like an answered prayer also soon became the venue of a nationally watched fight over unionization.

Why here? Amazon has more than 100 other warehouses, most of them larger, both in square footage and employee size, and almost all of them have been in place longer than Bessemer’s BHM1 site.

The answer, say locals, lies in the moment. The struggle to work and live amid the coronavirus pandemic, while Amazon founder Jeff Bezos saw his wealth rise $48 billion, has only fueled inequality frustrations. Workers at BHM1, an estimated 85% of whom are Black, also say the simultaneous focus on the Black Lives Matter movement encouraged them to fight for workplace justice.

But the answer also lies in this area’s history: a history that has already given much to the intersection of labor rights and civil rights.

“Birmingham has always been a city of struggle,” says Vincent Davis, a custodian at BHM1. “We’ve always struggled to make our mark on the world, and this is just another example of that.”

Tech giants – Facebook, Apple, and of course, Amazon – have successfully thwarted union efforts thus far. Amazon in particular has come under criticism for its reportedly harsh working conditions while squashing workers’ unionization efforts at other warehouses.

If BHM1’s almost 5,800 workers vote to unionize, it could reinvigorate a long-declining labor movement in the United States and potentially begin a domino effect across Amazon’s other facilities – redefining what it means to work for the country’s second largest employer.

Which is why a nondescript, tree-lined intersection along Powder Plant Road here has become the epicenter of a tumultuous contest over the power of workers. Leading up to March 29, the final voting day on unionization, several Democratic congressmen and women have made pilgrimages here, along with other celebrities.

President Joe Biden has reiterated his support for unions and workers in Alabama, without mentioning the Bessemer warehouse directly. Amazon has been waging its own all-out effort to persuade workers that unionizing isn’t in their interest.

“The reason that Amazon is putting so much energy to try and defeat you, is they know that if you succeed here, it will spread all over this country,” Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont said during a visit to Bessemer on Friday.

When asked if a union at the Bessemer warehouse would be a windfall for unionization efforts at other Amazon locations, Randy Hadley, a union organizer here, rolls his eyes and makes a faint whistle sound.

“We’re already getting calls from people asking about how they would start something like this at their location,” says Mr. Hadley. “What we’re doing here in Bessemer, Alabama, it’s opening people’s eyes to ‘Hey, we can organize if we do it together.’”

“Granddaddy would say, ‘You need a union’”

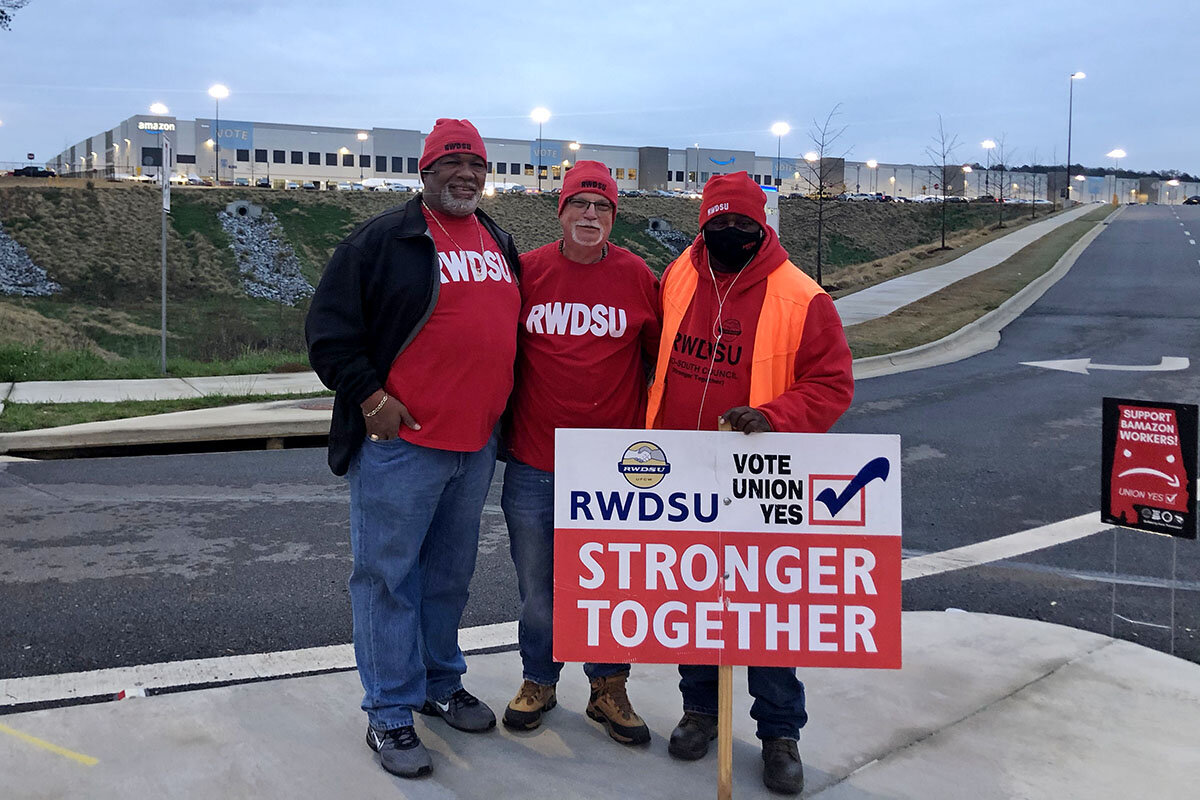

It’s just after 6 a.m., and Mr. Hadley has already been standing on the roughly 12-foot-long median outside the warehouse for hours, trying to catch employees on the shift change. It’s the traffic light seen across the country, where Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union organizers, or RWDSU as it is referred to around town, wave signs and try to hand flyers to workers leaving the facility during the 15-second red light. Mr. Hadley is president of the union’s mid-South council, which will represent BHM1 workers if they unionize.

Some drivers have yellow “Vote NO” signs hanging from their rearview mirror, and they pointedly stare away to avoid conversation.

Many cars and baby blue “Prime” trucks lay on their horns in support as they pass.

“I don’t think Amazon is telling the truth on a lot of things, so I’m for the union,” says one woman, before quickly driving away as the light turns green.

“Bessemer has a long tradition of labor unions,” says Mr. Hadley, who has been organizing on the ground in Bessemer with his colleagues since Amazon employees reached out to them last year.

“They’d go home and they would say, ‘Granddaddy, I’m being mistreated at Amazon,’ and the Granddaddy would say, ‘You need a union,’” says Mr. Hadley. “They just kept talking around the table like that, and at the churches, and I think that’s why they reached out to us.”

Steel boomtown

At the Bessemer Hall of History, a former railroad depot that periodically shakes with the passing of a train, relics of “The Marvel City” are displayed in foggy glass cabinets.

In the late 1800s, the city became a boomtown when the combination of iron ore, limestone, and coal – the three ingredients needed to make steel – were all found beneath Bessemer’s feet. The United States Steel Corp. soon took over operations, a company that notoriously took advantage of Black workers and southern discrimination laws. By the 20th century, many of the local plants had unionized.

But then in the early 1980s, U.S. Steel closed its nearby plant, the South’s largest integrated steel mill, because the company couldn’t come to an agreement with the United Steelworkers union. More than 3,500 employees were laid off.

“Do you know how easy it would be for Amazon to pick up and get out of here?” says Martha, a receptionist at a hotel chain not one mile from the plant, echoing a fear of many anti-union locals. Her father worked at U.S. Steel and was laid off due to the union disagreement. He eventually got a new job but it paid $400 less each month, says Martha, who declined to give her last name because she was on the job.

Alabama, like all other states in the Deep South, is a right-to-work state. This means that workers can’t be compelled to join a union or to pay dues for union representation – legislation that weakens the bargaining power of unions and is largely favored by corporations.

Carvana and Dollar General recently opened up distribution centers in Bessemer, although they only brought roughly 1,000 jobs, combined.

“Without all of this new industry, we would have turned out like Detroit or Allentown. Cities never come back from the dead, but Bessemer did,” says Martha. “Don’t kill the goose that laid the golden egg.”

If Bessemer’s Amazon employees unionize, it could have a ripple effect throughout the community. Mr. Davis, for example, the custodian at BHM1, is a contracted employee so he doesn’t have a union vote. But if the warehouse unionizes, Mr. Davis says he will be fired or have to be hired directly by Amazon.

What Amazon provides

A lot has been left out of the media coverage surrounding unionization at BHM1, says Heather Knox, director of communications for Amazon operations. Along with a starting salary that’s double the federal minimum wage, employees receive full benefits (“It’s the same health care benefits that I get,” she says), along with a 50% 401(k) match.

“I don’t know what the union is promising people,” says Ms. Knox.

Union organizers don’t say much about what direct benefits BHM1 employees will get with them. “Oh there is a specific demand on the table: respect,” says Mr. Hadley, when I asked him. “The rest will come later.”

Ms. Knox points out other Amazon programs, such as a 95% tuition reimbursement for continuing education after one year of employment. That is a benefit that many Bessemer employees will be eligible for on March 29.

“We’re really creating an opportunity that has a ripple effect in the community that didn’t exist before,” says Ms. Knox, on a phone call from the West Coast. “The truth is that the majority of people who come to work there every day love their job.”

Workers who have partnered with RWDSU say that’s not true. They describe work inside the warehouse as inhumane, fearing to take bathroom breaks for fear of missing seemingly impossible per hour quotas. And while an hourly wage of almost $16 is impressive in contrast to the local and federal minimum wages, they say it’s not enough to live on.

Pro-union employees and organizers say Amazon came to Bessemer for a reason: Amazon thought it would find poor, minority workers willing to take these jobs and not speak up. That view is shared by others who are standing in solidarity with them – including local representatives of the nationwide Black Lives Matter movement.

“BLM is involved [in the unionization effort] because the killing of Black people can happen on so many levels. If you can’t put food on your table, you can’t survive,” says Eric Hall, co-founder of the BLM Birmingham chapter, which has organized rallies in support of the union.

“In order for this labor movement to win, we have to marry these movements together,” says Mr. Hall. “It’s a fusion movement.”

“We are a city of drastic change”

Roughly 200 yards from the traffic light on Powder Plant Road, Eric Jones waits at the bus stop to take him home to Birmingham after his shift. The trip takes an hour and a half on the bus, but if Mr. Jones had a car, it would be less than 30 minutes.

Still, he likes his job. He works as a “picker,” which means he finds and picks certain items to be shipped, and he says he’s gotten really good at it. At first Mr. Jones could only pick 700 items an hour. Now, he’s gotten up to 1,000 an hour, and managers ask him to move to their floor if their quota is running behind. Also, the pay is $3 more an hour than what he was making before as a cook, and he doesn’t have to work on the weekends.

“Amazon gave me all the info about why not a union, but the union hasn’t told me what I’d get from them,” says Mr. Jones, who voted no. “Also, the union don’t tell me what I’d be getting but they still is aggressive. ... It’s like, I can speak for myself.”

Mr. Jones says he was recently interviewed by another reporter, and that reporter published the anecdote about his 90-minute commute. The next day, his Amazon manager came up to him and said she’d help him look into a program that would get him a car.

After 30 minutes of waiting, the bus finally arrives and Mr. Jones heads home to get some rest before doing it all again tomorrow. Mr. Davis, the custodian, stays on the bench, waiting for another bus. He’s quiet for a beat, and then sighs.

“I was born in ’64, right in the heat of civil rights. Older people would say, ‘We won here in Birmingham,’ and I’d say, ‘Won what?’” says Mr. Davis. “But we are a city of drastic change. We make others change even if we don’t change ourselves.”