Ohio’s Senate race highlights Republican divide on Ukraine

| Mansfield, Ohio

J.D. Vance – the bestselling author of “Hillbilly Elegy” who is running to fill an open U.S. Senate seat from Ohio – has staked out a largely hands-off position on the Russia-Ukraine conflict. “What should the federal government be doing in Ukraine?” he asks an audience of Mansfield, Ohio, voters in the Republican primary race. “I think the answer is ‘Not a whole lot.’”

The next day, at a campaign event in Canton, rival candidate and businessman Mike Gibbons takes a very different stance, supporting arming Ukrainians “to the teeth.”

Why We Wrote This

Prominent Republican voices have risen in support of Ukraine. But the party’s voters in Ohio reveal an American mindset that far predates Trumpism: a wariness of engaging in foreign conflicts.

The diametrically different views reflect a larger split playing out within the Republican Party over Ukraine – and, more generally, over American leadership abroad. As the world confronts the greatest threat to the global order in decades, the GOP is seeing a sharp resurgence of its traditional hawkish wing, even as its populist base, ascendant during the Trump years, continues a more isolationist emphasis on putting “America first.”

An aversion to boots-on-the-ground conflict is nothing new for Americans, says John Mueller, an expert on public opinion and war at The Ohio State University. Typically, he says, it takes an attack on American soil – think Pearl Harbor or 9/11 – to shift public opinion.

At a campaign event in a dark church basement in Mansfield, Ohio, an older man in a baseball cap leans back and asks Republican Senate candidate J.D. Vance about a controversial remark he made a few weeks back, in which he said he doesn’t “really care what happens to Ukraine.”

Mr. Vance – a former venture capitalist whose bestselling memoir, “Hillbilly Elegy,” detailed his hardscrabble Appalachian upbringing – quickly assures the audience that he has prayed for Ukraine in church the past three Sundays. But he makes clear his position on America’s role in the conflict hasn’t really changed. “What should the federal government be doing in Ukraine?” he asks. “I think the answer is ‘Not a whole lot.’”

The next day, at a campaign event in Canton, rival candidate Mike Gibbons tells the Monitor he is “100% behind the Ukrainians,” adding that he “would crush” Russia with economic sanctions and supports arming Ukrainians “to the teeth.”

Why We Wrote This

Prominent Republican voices have risen in support of Ukraine. But the party’s voters in Ohio reveal an American mindset that far predates Trumpism: a wariness of engaging in foreign conflicts.

The Republican businessman, who narrowly leads the multicandidate primary field in polls, says he told his wife he wished he were in better shape so he could go to Ukraine and fight the Russians himself. “Any help we can give [Ukraine], I would do it,” says Mr. Gibbons.

The diametrically different views on display here in Ohio, in one of the most expensive, most watched primary battles of the 2022 cycle, reflect a larger split playing out within the Republican Party over Ukraine – and, more generally, over American leadership abroad. As the world confronts the greatest threat to the global order in decades, the GOP is seeing a sharp resurgence of its traditional hawkish wing, even as its populist base, which had been ascendant during the Trump years, continues taking a more isolationist stance around putting “America first.”

Although former President Donald Trump recently called Russia’s invasion “appalling,” he has also praised Russian President Vladimir Putin’s moves in Ukraine as “smart” and “savvy.” North Carolina Rep. Madison Cawthorn called Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy “a thug,” while state-controlled Russian media has circulated clips of Fox News host Tucker Carlson questioning why “hating Putin” has become “the central purpose of America’s foreign policy.” Georgia Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene accused both Democratic and Republican leaders of having financial ties to Ukraine, warning in a Facebook Live video that “hard-working Americans living paycheck to paycheck don’t care about foreign wars or foreign borders.”

At the same time, Republicans favoring action are increasingly vocal. Mr. Trump’s former vice president, Mike Pence, recently said there was no room in the GOP for “apologists for Putin.” And top Republicans in Congress, from Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell to House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, have been pressuring the administration to increase sanctions on Russia and provide Ukraine with more support. South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham has publicly called for Mr. Putin’s assassination, while retiring Ohio Sen. Rob Portman – whose seat Mr. Vance, Mr. Gibbons, and others are competing to fill – recently traveled to Poland as co-chair of the Senate Ukraine Caucus, and has been urging the administration to send air assistance to Ukraine.

While most hot-button issues typically divide along party lines, the Ukraine-Russia conflict has jumbled alliances, says Ohio Republican strategist Mark Weaver. Far-right Republicans criticizing “the military-industrial complex” these days sound not unlike far-left Democrats of old. Meanwhile, more hawkish members of both parties have been urging President Joe Biden to take stronger action, with some all but accusing him of appeasement.

“Some people want us to do almost nothing, and some want us to send a lot of arms and have a no-fly zone,” says Mr. Weaver. “You are seeing that spectrum in this Ohio primary.”

“There are other issues here at home”

Ohio’s Senate race has generated an outsize amount of attention this year in part because it’s a rare open-seat contest. The fact that Mr. Trump has withheld an endorsement – a rarity that has garnered its own attention – has made the Republican primary even more competitive.

According to OpenSecrets, Ohio had the highest fundraising hauls in 2021 of any Senate race, with two of the Republican candidates, Mr. Gibbons and Matt Dolan, putting more than $10 million of their own funds into their campaigns. Voters here can describe in detail the campaign ads that have been blanketing their TVs and radios for weeks.

Still, a recent Fox News poll had “Don’t Know” leading the race with almost one-quarter of likely GOP voters. And more than 60% of voters said they may still change their mind. Even the date of the primary itself, currently slated for May 3, is up in the air. There’s a chance it will be postponed due to redistricting delays.

But when it comes to the Russian invasion, Ohio’s Republican voters display more consensus than their politicians. When asked to list their top priorities, more than two dozen people at GOP campaign events across the state cite the economy, election integrity, crime, abortion, the Second Amendment, and fortifying America’s southern border.

No one brings up Ukraine.

“A big one for me is feeling that our votes are going to count. After 2020 I feel hesitant to even cast a vote,” says Mike Barrett, a high school coach, at Mr. Vance’s event in Mansfield.

“For sure the economy,” chimes in his wife, Susan, a retired nurse. “I just got half a tank of gas and it cost me $47.”

When asked specifically about Ukraine, voters here don’t echo praise for Mr. Putin or criticism of Mr. Zelenskyy. Many say they pray for the Ukrainian people and are on board with the Biden administration’s economic sanctions against Russia.

The limits to their support, however, are clear.

“In the news we watch – Fox – it’s nonstop about Ukraine. And I understand why. We’re one step away from it coming here,” says Mr. Barrett. His wife interrupts: “But there are other issues here at home.”

Many audience members nod in agreement when Mr. Vance calls it a “disaster” that congressional Republicans more than doubled Mr. Biden’s request for $6 billion in Ukrainian aid, authorizing $14 billion “to protect the border of a country 6,000 miles away,” while failing to give $4 billion to Mr. Trump for his U.S.-Mexico border wall.

After Mr. Vance is asked about his past Ukraine comments, Matt Metcalf, a Richland county prosecutor, poses a follow-up: “I’m an America first person like yourself, but I don’t want to see Russia grow and spread communism,” he says. “When does that become a problem?” Mr. Vance replies that it’s a “different conversation” if Russia were to invade NATO allies, like Poland.

“It’s not that you have to be heartless, it’s ‘What is in our national interest?’” Mr. Vance says later in an interview, after another event in a fluorescent-lit community center in Canton. “I think most voters actually agree with me on that – and not just Republican voters. I think a lot of Democratic voters agree with that too.”

A recent ABC News/Ipsos poll found that almost 80% of respondents supported banning Russian oil imports, even if it meant higher gas prices, while less than one-third supported imposing a no-fly zone over Ukraine if it meant drawing the U.S. and its allies into “direct military conflict” with Russia.

This aversion to boots-on-the-ground conflict is nothing new for Americans, says John Mueller, an expert on public opinion and war at The Ohio State University. Typically, he says, it takes an attack on American soil to shift public opinion. It wasn’t until the bombing of Pearl Harbor that the U.S. became directly involved in World War II, and “almost everyone agrees that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan would not have been fought if it were not for 9/11.”

Even when America does become involved in conflicts overseas, domestic concerns often still dominate in politics. Professor Mueller points to former President George H.W. Bush, who saw his approval ratings soar at the end of the first Gulf War but then lost his reelection bid, in large part because of a poor economy.

“They thought he would win by a landslide because of his [Gulf War] victory,” says Mr. Mueller. “Foreign policy has hardly ever played that much of a role during elections, even during the Cold War. ... Voters worry about domestic stuff much more.”

Voters see energy as a national security issue

The war in Ukraine is amplifying certain domestic issues, however. Many voters here say it’s underscored for them that America needs to become more energy independent.

“I want that pipeline opened,” says Fran Leitenberger at Mr. Vance’s rally in Mansfield, referring to the Keystone XL pipeline that would have transported Canadian tar sands crude oil to U.S. refineries. Construction of the controversial pipeline, which had begun under Mr. Trump, ended when Mr. Biden canceled its permit upon taking office.

“It’s like we’re sitting on a gold mine, and we’re buying gold from everywhere else,” says her friend Brenda.

“Not even buying,” adds their friend Cindy. “We’re begging.”

In an interview ahead of a campaign event at the Sar Shalom Center in Mansfield, Republican candidate Josh Mandel goes so far as to blame the Russian invasion on Mr. Biden’s energy policy. If Mr. Biden had focused on ramping up domestic production, says Mr. Mandel, then the U.S. could have been exporting oil to Europe, undercutting Mr. Putin’s market and denying him the capital to invade Ukraine.

During his hourlong stump speech, Mr. Mandel praises “the Judeo-Christian bedrock of America” and the brave soldiers who fought in World War II, but never mentions the conflict in Ukraine. Afterward, a dozen pastors encircle the former Ohio state treasurer and pray – separately and out loud – for Mr. Mandel’s candidacy, as the hundred or so audience members stand, arms outstretched.

Other candidates echo Mr. Mandel’s Biden-energy argument.

“If we were energy independent, this attack would never have occurred,” says Mr. Gibbons to a nodding crowd of about 30 voters munching on chicken wings at an Irish pub in a Canton strip mall. “Putin has all the leverage on the world right now.”

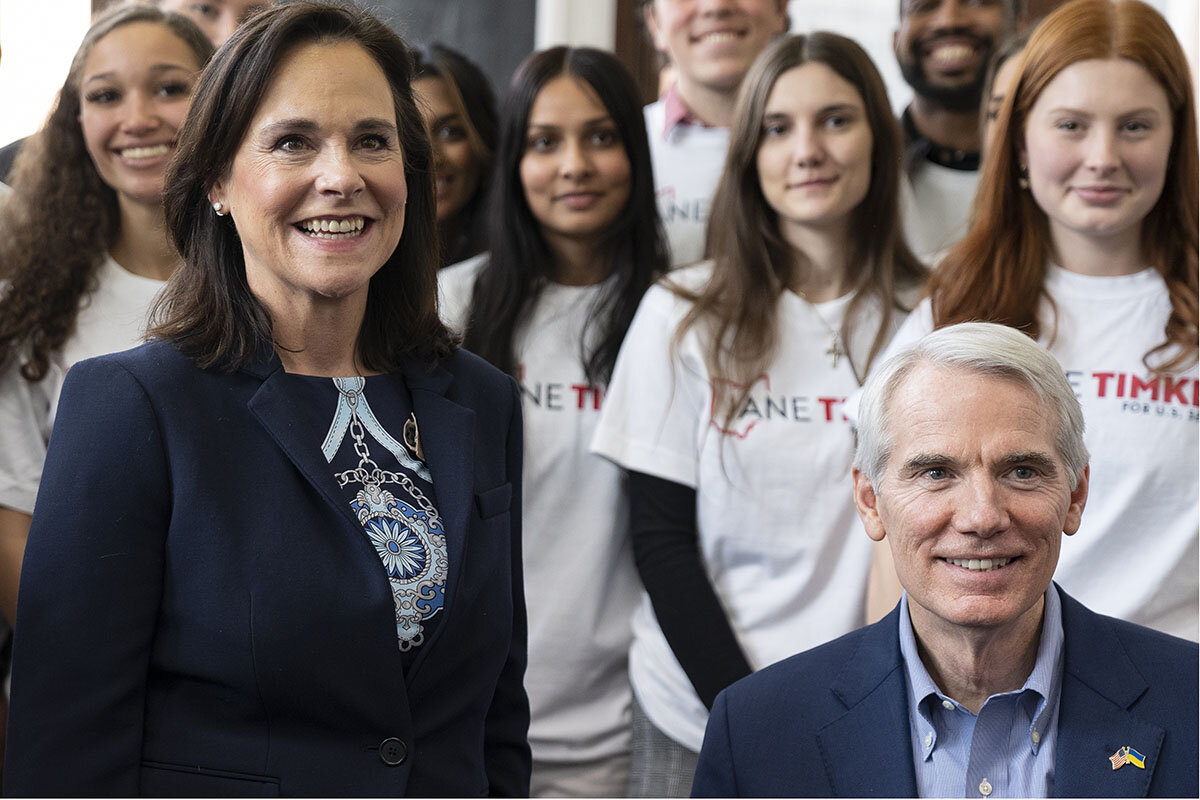

Fellow GOP candidate Jane Timken, a former chair of the Ohio Republican Party who has been endorsed by Senator Portman, says the Biden administration should have issued sanctions before the invasion, and that the White House could be doing more now to “squeeze Putin to the maximum capacity.”

In a phone interview with the Monitor, Ms. Timken notes that Ohio has one of the nation’s largest Ukrainian populations and says Ohioans of Ukrainian descent “are very concerned about what’s happening.”

According to the most recent U.S. census ancestry survey, roughly 40,000 people in Ohio report Ukrainian ancestry. Many of them live in Parma, a suburb of Cleveland dotted with Ukrainian Catholic churches and pierogi shops.

Mr. Trump won Parma by a few thousand votes in 2020. But people here aren’t focused on domestic politics right now – in part because they’re too busy worrying about their homeland and their families.

“Here I am safe, but I can’t be calm for one minute,” says Olena Boichuk, who moved from Ukraine to Parma with her husband five years ago, and whose parents are still in Ukraine. “I lived in some of these cities and now I see the pictures – they are gone.”

Ms. Boichuk is aware that the question of American involvement in the crisis is politically divisive. “There are two sides, and I see that. Any American can say, ‘Ukraine is far away. Why should we care?’”

Still, she says Parma’s Ukrainian population has been overwhelmed with support, with people coming into the Ukrainian Village Food and Deli where she works, saying, “I have never been here before, but I want to buy some things.” On a recent day when she arrived to open the shop, a bouquet of yellow and blue flowers – the colors of the Ukrainian flag – had been left on the doorstep.

“What makes me the most surprised is when Americans talk about Ukraine with tears. It’s very touching. That people are so not indifferent makes me cry,” says Ms. Boichuk. “I am always answering the phone at the store and people say, ‘Do you have any Ukrainian flags?’ And I say, ‘We are all sold out.’”