In key battlegrounds, races for secretary of state take on new weight

| Atlanta, Ga.

Most voters can’t name the secretary of state where they live. Traditionally a low-profile office, it doesn’t often merit much in the way of media coverage or fundraising when on the ballot, as it is in 27 states this fall.

In Georgia, however, GOP Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger has become a household name. His now-famous refusal to “find” 11,780 more votes for former President Donald Trump – and his insistence on the accuracy of the 2020 results in his state – made him both a hero to Democrats and a villain to many Trump supporters.

“There’s nothing wrong with saying, you know, that you’ve recalculated,” President Trump told Mr. Raffensperger in a recorded phone call that was later made public, after he’d recertified Joe Biden’s victory.

Why We Wrote This

A high-profile primary in Georgia is testing the salience of former President Donald Trump’s disproved claims of widespread fraud in 2020. At stake: oversight of the 2024 elections.

Now Mr. Raffensperger is facing a tough four-way GOP primary on May 24, in a contest that will test Republican voters’ concerns about “election integrity” and the salience of Mr. Trump’s disproven claims of widespread fraud. Whoever wins the primary, which polls suggest could go to a runoff, will face a Democratic opponent in November’s midterms.

Candidates hewing to Mr. Trump’s “election fraud” narrative are running for secretary of state in 17 of the 27 states where the office will be on the ballot in the fall, according to a nonpartisan watchdog group, the States United Democracy Center. And Trump-endorsed candidates are running in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Arizona, all states where Mr. Trump contested the 2020 results.

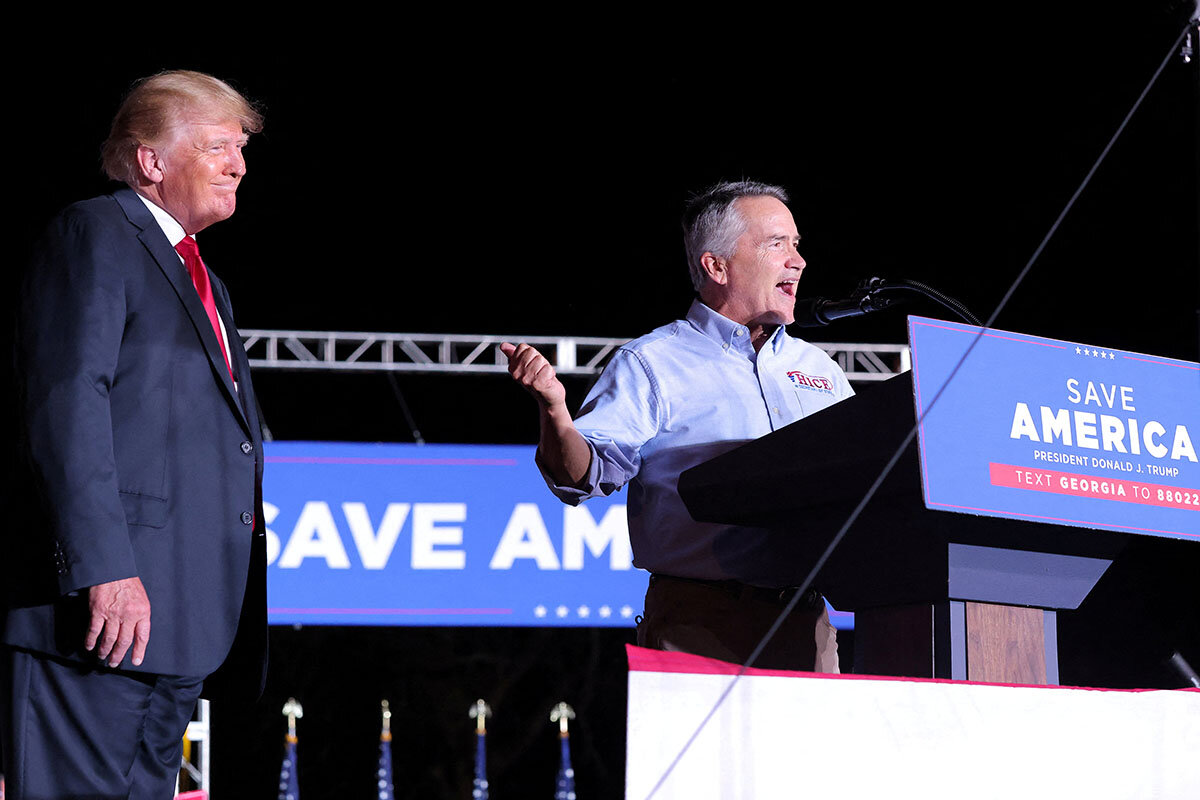

In Georgia, Mr. Raffensperger’s main GOP challenger, Rep. Jody Hice, has the former president’s endorsement. A member of the right-wing Freedom Caucus, he is quitting his House seat to run. In a May 2 debate, he accused Mr. Raffensperger of allowing fraud to taint elections in Georgia, calling it “the most insecure state in the country.” Other candidates said they would have done more to investigate the 2020 election – even after Mr. Raffensperger pointed to multiple recounts and efforts by law enforcement to find proof of machine or human fraud, all of which only served to reaffirm President Biden’s win.

The powers of secretaries of state can vary from place to place, but most are tasked with overseeing how votes are cast, counted, and certified. That can make them a crucial backstop against partisan meddling – or potentially, a thumb on the scale at election time.

Typically, secretaries of state “leave their party hat at the door” and serve all voters, says Tammy Patrick, a former federal elections official in Arizona. That norm may be tested by a slew of candidates who are running specifically on a platform of disproven or unprovable claims about 2020 – and who will be tasked with administering the 2024 election, when Mr. Trump is expected to run again.

In a democracy that relies on respect for the lawful transfer of power, that should concern everyone, says Ms. Patrick, who is a senior adviser to the Democracy Fund, another nonprofit. “You can vote for a candidate who stands for the rule of law, or a candidate who’s running on conspiracy and conjecture – because that’s all it is,” she says. “Elections have consequences.”

Discretionary powers

Republicans in Michigan have already chosen Kristina Karamo as their nominee. A community college instructor, Ms. Karamo rose to prominence in conservative circles after she claimed she witnessed fraud at Detroit’s absentee counting board, and later received Mr. Trump’s endorsement. In Wisconsin, where state elections are run by a bipartisan board, Republicans running for governor have said they would dissolve the board and put the secretary of state – or the legislature – in charge.

In 12 states, the secretary of state is appointed directly by the legislature or the governor. The latter is true in Pennsylvania, where Republicans on Tuesday chose Doug Mastriano as their gubernatorial nominee. Mr. Mastriano, a state senator, was an early supporter of Mr. Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 results, going to the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, and pushing to send an alternate slate of electors to Congress.

In a decentralized system, it often falls to local election officials to interpret complex rules determining which ballots are valid or not. Still, in close races, the discretionary power of secretaries of state can be critical.

Georgia is a case in point: In 2018 Stacey Abrams, the Democratic nominee for governor, lost by 55,000 votes to then-Secretary of State Brian Kemp. She refused to concede, accusing him of purging eligible voters from the rolls ahead of the election, a charge he denied. A federal lawsuit over her claims is ongoing. Ms. Abrams is making another run for governor this year.

And secretaries of state have been accused of tipping the scales in presidential elections. In 2004, Ohio Secretary of State Ken Blackwell, who was simultaneously serving as honorary co-chair of President George W. Bush’s campaign in his state, was accused of voter suppression for ordering poll workers to deny provisional ballots to voters who couldn’t confirm their address. After a recount, Mr. Bush was determined to have won Ohio by about 118,000 votes out of 5.5 million cast.

In 2000, a far smaller margin separated Mr. Bush from Vice President Al Gore in Florida. Secretary of State Katherine Harris, who had been appointed by Gov. Jeb Bush, the candidate’s brother, resisted demands for recounts in three counties. A lawsuit over her decision went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled it wasn’t possible to hold a timely recount, handing the presidency to Mr. Bush.

“2,000 Mules”

In Georgia, Mr. Raffensperger’s opponents have seized on a documentary by conservative filmmaker Dinesh D’Souza called “2000 Mules” alleging widespread ballot collection by third parties, which is only allowed in Georgia among family members. Its claims rely on supposedly suspicious patterns of movement in cellphone tracking data, which critics counter could easily be attributable to other things. On Tuesday, Georgia’s elections board – consisting of three Republicans and one Democrat – voted unanimously to dismiss three cases of alleged “ballot harvesting” after investigators determined the ballots in question were from family members living in the same households. One of the cases had relied on footage shown in the film.

Indeed, for all the election-related accusations traded in Georgia, the most prominent criminal investigation to date involves the pressure former President Trump put on Mr. Raffensperger. Earlier this month, a special grand jury was selected in Fulton County to look into whether Mr. Trump and his allies violated Georgia’s laws against election interference. The jury will sit for up to one year.

For his part, Mr. Raffensperger is doggedly defending his oversight of the 2020 election, while proclaiming his support for Georgia’s 2021 election law that tightened the rules around casting ballots by mail. Democrats have assailed the law, which will also allow state legislators to replace county election boards in some circumstances. Mr. Raffensperger has also begun calling for a constitutional amendment against non-citizens voting in Georgia, which is already a criminal offense.

His primary opponents enjoyed a head start because Mr. Raffensperger, as a state officeholder, couldn’t campaign until Georgia’s legislative session ended in April, notes Amy Steigerwalt, a politics professor at Georgia State University. This made it harder to refute what his GOP rivals were saying about his record. “You had unanswered claims across the airwaves,” she says.

And while Mr. Raffensperger won the respect of Democrats and independent voters for standing up to President Trump, which could help him in a general election, many in the GOP base hold a dim view of his actions.

“Raffensperger is in a lot of trouble. He could very well lose,” says Alan Abramowitz, a professor of political science at Emory University who studies elections.

Finishing up his breakfast at a diner in Ludowici, a rural county seat in southern Georgia, Henry Korrecta shakes out a fistful of pills on a napkin. A retired Army veteran, he says he cast an early primary ballot for Representative Hice as secretary of state. “We need a true conservative. [Mr. Raffensperger’s] not a true conservative,” he says. “He’s got to go.”

Likewise, Lynn Savage, an artist and Republican voter in Jackson County, wants Mr. Raffensperger gone. “We saw fraud [in 2020] and nothing was done about it,” says Ms. Savage. She believes something nefarious happened with the voting machines, despite the fact that the state had replaced its paperless voting machines prior to the 2020 election. “You can manipulate a computer. There were lots of [bad] things going on,” she says. Georgia conducted a hand recount of every vote cast, which reaffirmed Mr. Biden’s win.

At a civic meet-and-greet in Macon, state Rep. Robert Dickey agrees that Mr. Raffensperger is facing a serious challenge. But the Republican legislator, who represents a central Georgia district, also believes the grassroots anger over the 2020 election is beginning to subside, despite Mr. Trump’s efforts.

“I think people are ready to move on,” he says.