They worked on Watergate. Here’s how they see the Jan. 6 hearings.

Loading...

| Washington

They were practically kids back then – most of them at least – when the Senate Watergate committee was announced, and they wanted in. One, a young Senate elevator operator, closed the door on a senator’s arm and wouldn’t open it until he agreed to pass along her résumé. Another got a job by promising to help a senator clear out a backlog of 10,000 letters. Others landed positions when their former Georgetown law professor Sam Dash was named chief counsel. Few had robust experience.

They photocopied $100,000 worth of bills to trace their serial numbers, interviewed witnesses in a windowless room dubbed the “dungeon,” and encountered countless dead ends, such as calling every Miami locksmith in the Yellow Pages to find the one who had changed the lock on a safe – only to have him say he couldn’t recall whether he’d seen stacks of cash.

From May to November 1973, as many as 80 million Americans tuned in to watch their committee unravel a web of misdeeds that started with a “third-rate burglary” in the Watergate office buildings and led to a broad pattern of corruption within the White House.

Why We Wrote This

Two presidents. Two investigations. Two very different eras. We talked to people involved in the 1973 Watergate hearings about today’s Congress and the pursuit of facts in the Jan. 6 Capitol attack.

Today, the staffers who cut their teeth on Watergate are in the twilight of their careers or retired. Nearly a dozen of them talked with the Monitor about how they see the Jan. 6 hearings. They bring a unique perspective, given their roles on a bipartisan investigation that persuaded a nation that the president who had just been reelected in a landslide was not fit for office.

Some of these former staffers see in the Jan. 6 hearings a group of lawmakers who have carefully studied – and emulated – their own committee’s work, often held up as the gold standard of congressional investigations. They praise the Jan. 6 House select committee for doing an admirable job in a far more divided era. One of Congress’ functions is to inform – and this committee, they say, is informing the public, as well as legislators and other officials, on a matter at least as grave.

“You can always nitpick,” says James Hamilton, an assistant chief counsel on the Watergate committee, acknowledging criticisms that snippets of video are being selectively presented and some of the testimony is hearsay. But he adds, “The overall effect and import of what they’re presenting should not be outweighed by these criticisms.”

Others, however, would have preferred more of the Watergate committee’s impartiality, with more GOP participation and robust questioning. At stake is not only the outcome of this investigation, but also the ability of the legislative branch to serve as a check on the executive branch. When that wanes, it’s not good for either party, says Searle Field, who worked for Sen. Lowell Weicker, one of three Republicans on the Watergate committee. “At the end of the day, Congress loses its credibility.”

Even if the Jan. 6 committee could have done more to project fairness amid the current polarization in media and politics, former House historian Ray Smock says it would be unreasonable to expect it to overcome those forces.

“This committee is not going to solve the deep divisions that have been in our country for many, many years,” says Dr. Smock, co-editor of a two-volume tome on congressional investigations. “And in fact, they may exacerbate those divisions.”

Long-running soap opera vs. Netflix special

For 20 hours a day, former elevator operator Emily Sheketoff buried herself in the Watergate investigation. When the young investigator for the GOP minority wasn’t in Miami calling locksmiths, she was working in a converted Senate auditorium with dozens of other staffers from both parties.

Despite the long hours, and the stream of celebrities like John Lennon and Yoko Ono attending the hearings, she didn’t fully realize the impact the committee’s work was having until the end of the summer when Fred Thompson, the top GOP lawyer on the committee, took a group out for drinks before one staffer headed back to college.

“People started applauding us as we walked in,” she recalls. “That’s how many people were watching this every day. It was like a soap opera.”

The Watergate hearings were broadcast for 237 hours. The Jan. 6 hearings, by contrast, have aired for fewer than 20 hours so far. The June 9 opening night attracted 20 million viewers – a quarter of Watergate’s peak audience.

Part of that is America’s reduced attention span. But in a way, the story of the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol is also an easier story to tell than Watergate, since much of it unfolded in public. The committee has been able to incorporate videos from that day, along with selected clips of depositions, police radio recordings, screen grabs of Twitter and texts, and other multimedia components, all woven together with the help of a former ABC News producer.

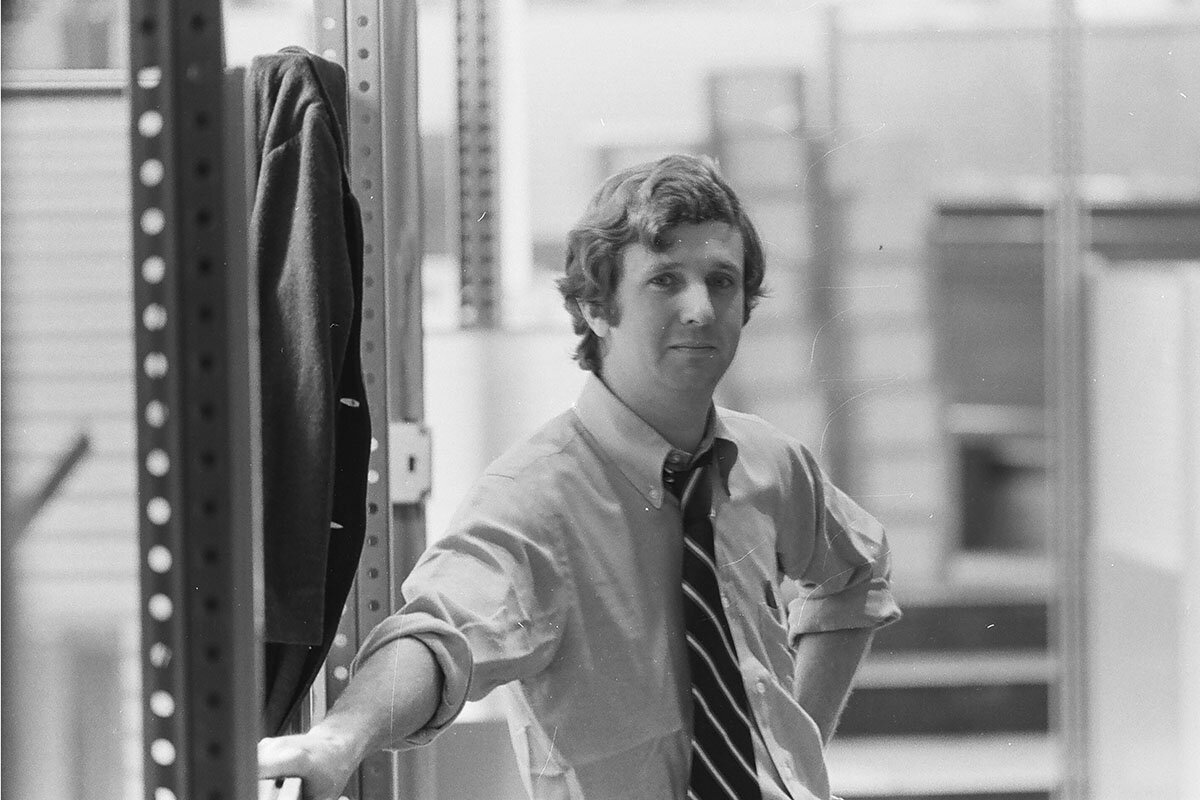

“To me, this is choreographed almost like Netflix. Ours were much messier. ... We were discovering things as we went,” says Gordon Freedman, a college student from rural Michigan who left before final exams to stand in line for the hearings each day and later got himself a job on the committee.

One Saturday night, Mr. Freedman was heading to a party when he heard on his car radio that President Richard Nixon had just shaken up the Justice Department, and the young staffer had to make a detour to grab his files in case the FBI raided the committee’s office.

But while the Jan. 6 committee has more technology at its disposal, these former staffers say its job is harder in other ways.

“We weren’t fighting the head winds of Trumpism,” says Ms. Sheketoff.

Whereas the Watergate committee was established with a 77-0 vote in the Senate, only two Republicans supported the formation of the House select committee on Jan. 6: Rep. Liz Cheney and Rep. Adam Kinzinger, both outspoken critics of former President Donald Trump.

Ms. Cheney and Mr. Kinzinger, the only two Republicans serving on the committee, have become virtual pariahs within the GOP. Neither had the support of Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, who boycotted the committee after Speaker Nancy Pelosi vetoed two of his five nominees.

In contrast, Ms. Sheketoff and others who worked for Republican senators on the Watergate committee say their bosses faced no partisan pressure from GOP colleagues.

Mr. Field recalls joining Senator Weicker for nighttime conversations in the street with the senator’s neighbor, John Dean, who had served as White House counsel until that spring and would prove to be one of Watergate’s most pivotal witnesses. Barry Goldwater Jr. also lived nearby, and his father, the Arizona senator, would sometimes join them. During one such meeting, Mr. Dean said he was going to have to refute the president, and Senator Goldwater encouraged him to go ahead, putting the truth ahead of partisan interests.

“You can’t imagine a senior Republican today saying to go after Trump,” says Mr. Field.

“Right back in another Watergate era” – but with a weakened Congress

As much as the revelations of President Nixon’s behavior shocked the nation, many of the Watergate staffers – though not all – see an equal if not greater threat in the Jan. 6 attack.

“I think this committee is doing a superb job of bringing to the attention of the American people the lengths to which the administration has violated laws and morals,” says Bill Shure, who served as an assistant counsel for the GOP minority. “I think what they’re doing is absolutely essential to alert the American people to how much danger democracy is in.”

On the eve of a staff reunion last month, held on the 50th anniversary of the Watergate break-in, some of the surviving staffers organized and signed a letter highlighting the threats to democracy today. They urged the nation to reflect on Watergate and consider what further reforms are needed. They see themselves as guardians of a special chapter in American history – one with renewed relevance today.

“We’re right back in another Watergate era; we didn’t learn the lesson long,” says Rufus Edmisten, the committee’s deputy chief counsel and the most senior staffer living today.

For almost 10 years before Sam Ervin was appointed chairman of the Watergate committee, Mr. Edmisten had worked for the jovial North Carolina senator, driving him around in a rickety Chrysler and serving as his chief counsel on a congressional subcommittee on the separation of powers. Senator Ervin, who was tapped by Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield as a respected constitutionalist with no presidential ambitions, viewed Congress’ investigative role as central to holding other branches of government accountable.

Today, many Watergate staffers see a Congress that has been internally weakened by partisan polarization, significantly hindering its ability to act as a check on the executive branch. In recent years, it has avoided thorough investigations of controversial issues, from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan to systemic problems in the economy.

“How are they going to be a powerful part of the separation of powers when they can’t even get their own house together?” asks Mr. Edmisten.

The Jan. 6 committee’s credibility challenge

The divide in Congress in many ways reflects growing polarization in the country, including in media. While MSNBC and CNN have provided hours of blow-by-blow commentary and analysis of the Jan. 6 hearings, Fox News opted not to even air the first hearing, held in prime time. And while Fox aired the subsequent daytime hearings, many of its viewers have responded by changing the channel.

Polls show that Mr. Trump’s popularity has barely been dented since the hearings began on June 9, despite extensive testimony from former Trump administration officials that he was told there was no evidence of widespread fraud in the 2020 election, and that blocking the counting of electoral votes would be unconstitutional.

Since the first hearing, the former president’s average favorability rating has dropped by fewer than 2 points, to around 40%. A poll conducted within two weeks found that a similar proportion, 38%, did not consider the hearings to be fair and impartial while 60% did.

Nevertheless, some Watergate committee staffers believe a more open-ended investigation with more GOP members, a wider scope, and more robust questioning could have increased the committee’s credibility in the eyes of the American public.

“If that were done, you would get a broader understanding and acceptance of what is going on with these hearings,” says Barry Schochet, an assistant majority counsel whose ’70s handlebar mustache became a fixture behind Democratic Sen. Herman Talmadge of Georgia during the hearings. He would have liked to see the investigation examine not only Mr. Trump’s culpability but also whether his administration sought additional protection for the Capitol ahead of Jan. 6 and whether there are civil liberties issues involving a number of people arrested in connection with Jan. 6 who remain in jail a year and a half later.

To some, it seems as though the Jan. 6 committee knew where it was heading from the outset and pursued a single-minded line of inquiry to get there.

“They were working toward a conclusion that they already anticipated and expected and hoped would be the conclusion, instead of proceeding with ‘What is the truth?’ and doing examination and cross-examination,” says Gene Boyce, who was brought on for his trial experience in the courtroom and was part of the interviewing team that got White House scheduler Alexander Butterfield to reveal that President Nixon had a secret taping system.

But at least one witness brought before the Watergate committee doesn’t feel that those hearings were an impartial search for truth, either.

“Watergate was really aimed in a political sense against Nixon,” says Donald Segretti, who was recruited by White House aides to execute political “dirty tricks” against the Democrats. It was “more of a political show than the Jan. 6 hearings, which are much more of a factual presentation.”

Is real bipartisanship still possible?

The Watergate committee has often been held up as a paragon of bipartisan comity. In reality, however, partisan divisions and suspicions caused significant turmoil, particularly in the early days. GOP Sen. Howard Baker was seen as too cozy with the White House, and GOP Sen. Edward Gurney was accused of being a Nixon apologist. But Chairman Ervin and Vice Chairman Baker made a pact that in public, they would present a united front. In one instance, Senator Baker reamed out chief counsel Dash behind closed doors for leaking information, then walked out and told reporters he had full confidence in Mr. Dash. Many of the committee’s decisions, including to subpoena the Nixon tapes, were unanimous.

Mr. Edmisten says Senator Ervin would be disappointed by the animosity between the two sides today. “It is impossible to set up a Watergate-type committee,” he says.

“I would wonder whether Senator Ervin would have ever put on the hearings were cross-examination not allowed,” says Mr. Schochet.

One of the GOP picks whom Speaker Pelosi vetoed was Rep. Jim Jordan, a Trump ally who was in touch with the president and senior White House officials on Jan. 6, and could be seen as having a conflict of interest. Some on the right see his tough questioning style as just what is missing from these proceedings, while critics say it would have derailed them.

“I understand why Pelosi vetoed Jordan,” says Mr. Hamilton, author of the forthcoming book Advocate on his 50 years in law and politics, which included representing retired Adm. Mike Mullen during one of the 2013 Benghazi hearings. “Jordan was disrespectful to Mullen and interrupted most of his answers.”

“The good part is that we don’t have what I’ll call flamethrowers on either side [who are] just grandstanding,” says Mark Biros, an assistant majority counsel and Dash student who went on to teach at Georgetown Law School for decades. “You’ve got what appear to be very serious people, thoughtful people, attempting to get at the facts as best they can.”

It is highly unusual, if not unprecedented, for the majority to reject the minority’s choice of committee members, especially in such a public way, says Mr. Smock, the former House historian who now serves as interim director of the Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education at Shepherd University. And two of Speaker Pelosi’s own picks are seen by many on the right as highly partisan: Reps. Adam Schiff and Jamie Raskin, who oversaw the first and second Trump impeachment proceedings, respectively.

Still, many disagree with Mr. McCarthy’s decision not to participate, with some calling it a deliberate ploy to undermine the committee.

“You can’t take your marbles and go home and then complain that you weren’t allowed to play,” says Ms. Sheketoff.

As much as these Watergate staffers would like their committee to be held up as a standard for congressional investigations, there is a resigned sense that, for now, its bipartisanship would simply be impossible to replicate in today’s environment.

“It brought independent views, without any sort of animosity,” says Donald Burris, an assistant counsel for the Democratic majority, who recalls shooting hoops with Mr. Thompson, the minority counsel. “It’s like nothing else I’ve done in my life. It seemed like a kind of civic service.”