How America lost trust in elections – and why that matters

As the United States plunges toward the 2024 presidential vote, it is clear that millions of citizens no longer trust an essential element of American democracy: elections.

Electoral trust has been gradually declining in the U.S. for over two decades, according to polls. The slump’s roots go as far back as Democratic anger over the Supreme Court essentially deciding the 2000 vote for George W. Bush. More recently it has been accelerated by Republican voters’ acceptance of former President Donald Trump’s false narrative that the 2020 election was stolen and parts of the nation’s electoral process are rife with fraud.

Today, sustained attacks by Mr. Trump have helped turn electoral trust into one of the most polarized issues in America’s polarized politics. Only 22% of Republicans have high confidence that votes will be counted accurately in 2024, according to an Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research poll from last year, compared with 71% of Democrats.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onDoubts about election integrity vary by party. But in general, they’ve been growing in recent years, raising concerns about the peaceful transfer of power in U.S. democracy.

Overall, only 44% of Americans have a “great deal” or “quite a bit” of confidence the vote count will be accurate in 2024, according to the AP survey.

Whatever the cause, such low levels of trust threaten to erode the U.S. democratic system, experts say. Citizens who don’t think votes are counted accurately are less likely to vote at all. They have less confidence in their leaders and can be more prone to violence – such as the insurrection at the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

“The danger that I see to American democracy is if one side consistently mistrusts elections. That’ll threaten this concept of loser’s consent, where the side that loses agrees to go along with the outcome and try again next time,” says Thad Kousser, a professor of political science at the University of California, San Diego.

From Boss Tweed to the Voting Rights Act

To some degree, distrust in U.S. election outcomes has been part of the nation’s political culture for centuries. It was fed in the late 1800s by the blatant fraud schemes of Democratic urban machines, which included stuffing vote boxes with reams of ballots pre-printed with approved slates of candidates. “I don’t think there was ever an honest election in the City of New York,” the notorious Tammany Hall leader William “Boss” Tweed once testified before the Board of Aldermen.

Reforms meant to rein in some of these abuses were an important part of the Progressive Era of the early 1900s. They included laws establishing the direct election of U.S. senators, processes for referendums whereby citizens vote on some issues directly, and a movement for women’s voting rights.

Moves to ensure more citizens could vote continued during the rights revolution of the 1960s. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 aimed to end the suppression of Black citizens’ ballots. Later, the enactment of the 26th Amendment to the Constitution in 1971 lowered the voting age for all U.S. elections to 18.

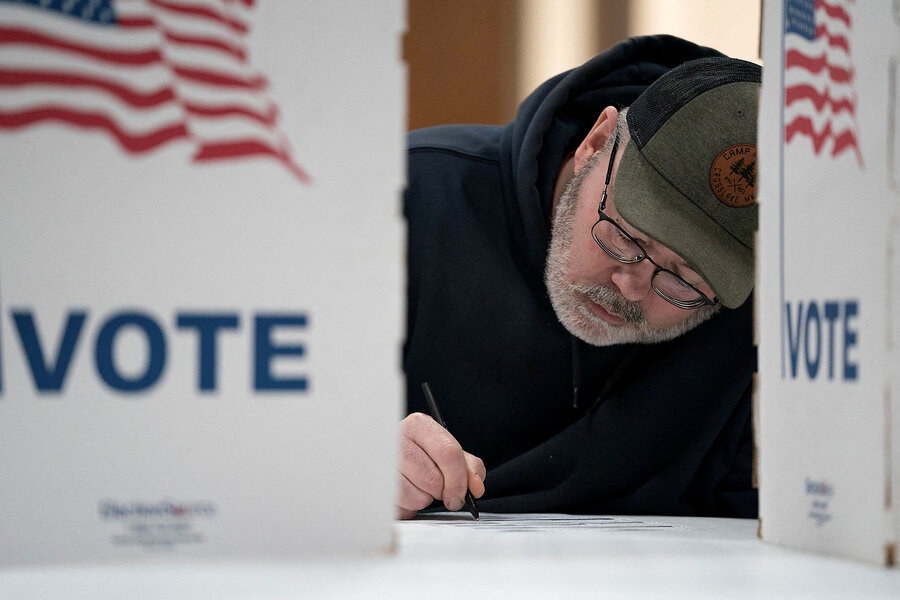

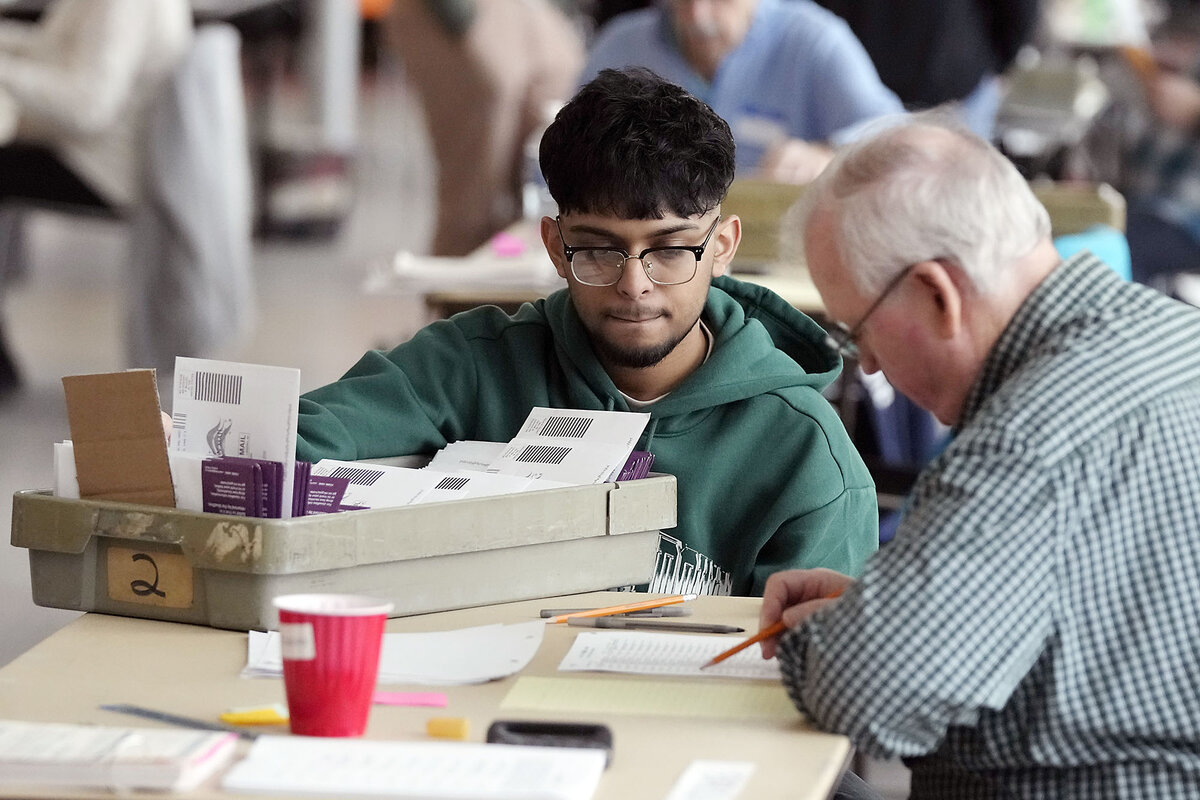

The 1980s saw states begin to ease rules on absentee ballots, allowing citizens to cast votes in person prior to Election Day, or for ballots to be mailed to all eligible voters. This trend peaked in the 2020 election with a raft of accommodations designed to ensure people could vote during the COVID-19 pandemic.

By measures of access, U.S. elections in the 21st century have become more open than ever. That is an important component of trust for Democratic-leaning citizens, polls show. But at the same time, in recent decades, a number of factors began pushing public opinion, on both the left and right, in the other direction, toward a crisis of confidence in elections.

Though that crisis is currently more widespread on the right side of the political spectrum, it is not hard to see how events in the 2024 election cycle could engender similar feelings on the left, according to a report by two dozen experts on law, elections, and information security.

“No longer can we take for granted that people will accept election results as legitimate,” stated the report, titled “24 for ’24: Urgent Recommendations in Law, Media, Politics, and Tech for Fair and Legitimate 2024 U.S. Elections” and produced under the auspices of the Safeguarding Democracy Project at UCLA’s School of Law.

“Did your team win?”

It’s difficult to measure the loss of trust in elections accurately with traditional public opinion methods, experts say. “Trust” is a broad concept that covers many different emotions.

But one major reason is the winner-loser effect: the well-documented phenomenon whereby a party or person’s trust in an election tends to rise if their candidate wins, and fall if they lose.

It’s human nature. A fan watching a baseball game is less likely to trust a close call that goes against their team. A close call against the opposing team, however, seems fair. When it comes to elections, trust and mistrust often come and go, rising and falling for one party or the other over the years.

“These ebbs and flows are usually determined by, ‘Hey, did your team win or lose?’” says Professor Kousser.

Nor is electoral trust a long-studied subject. It was only after the Bush-Gore election of 2000 that political scientists began to look at it in a systematic way.

As an election, the razor-close contest between Republican Texas Governor Bush and Democratic Vice President Al Gore was a mess.

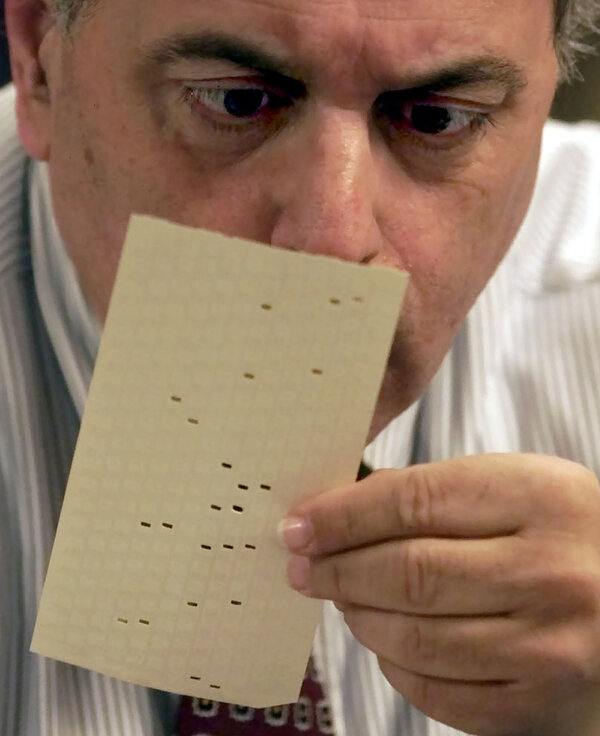

It all came down to Florida. Palm Beach’s “butterfly” ballot, in which the name of the candidate was misaligned with the space voters pressed to mark their choices, confused many people. Other locales used punch-out ballots, which were difficult for some voters to punch out cleanly, leading to the “hanging chads” of paper that weary election officials were tasked with evaluating.

A five-week legal battle followed. Democratic lawyers pushed for recounts, while Republicans sued to block them. Finally, after legal twists and turns in the state courts, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 5-4 to stop the process. The ruling effectively delivered the state, and the presidency, to Governor Bush by a margin of some 500 votes.

Bush v. Gore remains one of the most politically consequential Supreme Court decisions in American history.

“Bush v. Gore was a turning point, not only in marking elections as something to be trustful or mistrustful about, but also in marking the Supreme Court as something to be trustful or mistrustful about,” says Charles Stewart III, professor of political science and director of the Election Data and Science Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

On Jan. 6, 2001, then-Vice President Gore had the painful duty of presiding over his own loss in his role as president of the Senate.

As Congress voted state by state to certify the election, 20 members of the House, most of them members of the Congressional Black Caucus, rose one by one to file objections to Florida’s electoral votes.

No senators joined them – a requirement under federal law for their challenge to be considered. So Mr. Gore, as presiding officer, slammed down his gavel to rule them out of order.

“We did all we could,” Florida Democratic Rep. Alcee Hastings said to Mr. Gore as the protest fizzled.

“The chair thanks the gentlemen,” Mr. Gore replied with a smile.

Rising distrust on the right

By 2004, Democrats were watching closely for any signs that election integrity might be compromised and affecting outcomes. Two congressional Democrats filed an objection to certifying Ohio’s Electoral College votes, citing alleged irregularities in both vote counting and public access to voting stations.

After President Bush’s reelection that year, Republicans had considerably more trust in the election system than Democrats did. Eighty-seven percent of self-described Republicans were very or somewhat confident that votes were counted accurately in the election, according to Gallup polling. Fifty-nine percent of Democrats felt the same way, as well as 69% of independents.

But by the eve of the midterm elections in 2022, GOP electoral trust had fallen to 40%, according to Gallup. Democratic trust had risen to 85%.

What happened?

Former President Barack Obama, for one thing. Mr. Obama’s 2008 victory and 2012 reelection led to a sharp slump in the Republican trust figure, and a gradual rise for the Democratic one. The factors at work, many analysts say, included latent racism surrounding the nation’s first Black president, intertwined with a “birther” movement falsely questioning his citizenship.

Then Donald Trump came onto the scene. Mr. Trump’s 2016 election did cause Republican trust in voting to increase. But then came his defeat in 2020 – and his dogged insistence that the vote had been rigged, despite a lack of evidence and repudiations by the courts – as well as a less-than-impressive showing for the party in the 2022 midterms. It all drove GOP approval of the U.S. election system to historic lows in Gallup’s polling series.

Generally, individuals will say they approve of their own voting experience, and think their ballot was accurately tallied, unless they deal with unexpectedly long lines or face some sort of equipment malfunction. Far more common is suspicion about what happens in other precincts or states.

In that context, what party leaders and authority figures say matters. Mr. Trump spoke darkly of fraud and cheating in elections even prior to his 2016 win. In 2020, he claimed on Election Day that he had actually won. His followers stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, seeking to stop the Electoral College counting. Since then, his false insistence that the election was rigged has become an article of faith among not just his most ardent supporters but Republicans in general – and something that other GOP leaders question at their peril.

Trust in elections has long been an elastic issue – one that U.S. political parties change their minds about, and flip positions on. But it is now possible that it has been polarized, like abortion or immigration, with fixed views on the GOP side, at least.

“I think there is going to be this persistent, organized distrust of a lot of elements of the election system among Republicans,” says Professor Stewart. “It could [also] be among Democrats under the right circumstances, but right now it is among Republicans.”

This dynamic has driven calls for hand-counting of ballots, withdrawals from a multistate partnership that checks registrations to clean up voter rolls, and anger toward local election officials, says Professor Stewart.

“It could also potentially lead to violence,” he says.

As the 2024 campaign gears up, Mr. Trump has only intensified his dark rhetoric about the American electoral system. He routinely promises to pardon those convicted of crimes on Jan. 6, though hundreds were charged with assaulting police. These “hostages” are “unbelievable patriots,” he often says.

He continues to demean mail-in voting despite lack of evidence, telling Laura Ingraham earlier this year that “you’re going to automatically have fraud” if it is allowed.

Job applicants at the Republican National Committee are now reportedly asked whether they agree the last presidential election was stolen. At rallies, Mr. Trump continues to insist he was robbed, though he wasn’t.

“Radical left Democrats rigged the presidential election of 2020, and we’re not going to allow them to rig the presidential election of 2024!” Mr. Trump said in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, earlier this year.

He portrays the coming election not as a civic choice that is part of a centurieslong tradition of parties losing and winning but as an apocalyptic event.

President Biden’s administration seeks “to collapse the American system, nullify the will of the actual American voters, and establish a new base of power that gives them control for generations,” Mr. Trump told a North Carolina audience in March.

The task of rebuilding trust

GOP election denialism is not all-encompassing. Republican officials such as Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger were key defenders of the system’s integrity in 2020, after all.

In the aftermath of the 2022 midterm elections, there were not widespread complaints about alleged fraud, despite the fact that an anticipated “red wave” of GOP gains didn’t happen. Defeated Arizona GOP gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake did pursue fraud charges in court, without success, but she may have been the exception that proved the rule. Like Mr. Trump, she had made warnings of a possibly stolen result a core part of her political identity prior to the election.

Recent polls have also shown some bounce-back from the lows of GOP electoral trust following 2020, even in many hotly contested swing states.

About one-quarter of Republicans say they believe President Biden fairly won election in 2020, according to a survey taken late last year by the Johns Hopkins SNF Agora Institute and Gallup. Another 12% say they are unsure about the outcome.

This group is a moveable section of the GOP electorate that is open to messages that U.S. elections are secure and the system is not rife with fraud, says Scott Warren, a fellow at the Agora Institute, via email.

Still, rebuilding trust in U.S. elections will require a bipartisan effort, according to Mr. Warren. Too many democracy reform initiatives don’t involve conservatives in any substantive way.

Increased public outreach and more transparency on the part of election officials about how the system works are important first steps, according to a set of conservative principles for building electoral trust produced by the Agora and the R Street institutes last year.

“It definitely won’t solve everything, but is a needed step,” says Mr. Warren via email. “The more work that can be done in this sector, the better.”