Jimmy Carter and Demetrius Young died the same day. Georgia will miss them both.

Loading...

| Augusta, Ga.

Last week’s passing of former President Jimmy Carter, perhaps America’s most beloved centenarian, led to heartfelt messages from his native Plains, Georgia, and throughout the world. His wasn’t the only stunning loss that Georgia would experience that day. Forty-five minutes from Plains, in the town of Albany, the passing of another public servant with a legacy of helping others also would send shockwaves through the region.

Demetrius Young, a city commissioner and statewide political activist, died Dec. 29. He was a second-generation politician, the son of Mary Young-Cummings, a Georgia state representative and civil rights attorney. He was also the direct descendant of a civil rights campaign – the Albany Movement.

Why We Wrote This

Jimmy Carter and Demetrius Young both died Dec. 29. The two men shared a life of service, a love of Georgia, and a care for the needs of everyday people.

This modest corner of southwest Georgia impacts the world because of its attention toward the needs of everyday people. President Carter’s roots as a peanut farmer from Plains are well-documented, and even the name of his hometown suggests simplicity and commonality.

Both men remind me that a number of great stories start from humble beginnings, but extending that grace throughout one’s life can make you larger than life.

Last week’s passing of former President Jimmy Carter, perhaps America’s most beloved centenarian, led to heartfelt messages from his native Plains, Georgia, and throughout the world. His wasn’t the only stunning loss that Georgia would experience that day. Forty-five minutes from Plains, in the town of Albany, the passing of another public servant with a legacy of helping others also would send shockwaves through the region.

Demetrius Young, a city commissioner in Albany and a statewide political activist, died Sunday evening, Dec. 29, less than two weeks short of his 54th birthday. I met him in a sports group and bickered with him a good bit over his support of the Atlanta Falcons and Florida State’s football team. Then I learned just how much of a gregarious man and giant he was. He was a second-generation politician, the son of Mary Young-Cummings, a Georgia state representative and civil rights attorney. He was also the direct descendant of a civil rights campaign – the Albany Movement.

Calling him a champion of voting rights would be an understatement. Much like his descendants in the struggle, he would push back against draconian laws despite threats of violence. Mr. Young and other volunteers were charged for handing out water and snacks to early voters during the 2020 election, claims that were dismissed over two years later. “You know, the half has not been told on, about what we went through that whole elections period,” he told Georgia Public Broadcasting News in 2023. “We were the ones that were threatened with violence, guns pulled on us, but we were the ones who were threatened with arrest from the local officials there. We were the ones who had to endure charges and things of that nature.”

Why We Wrote This

Jimmy Carter and Demetrius Young both died Dec. 29. The two men shared a life of service, a love of Georgia, and a care for the needs of everyday people.

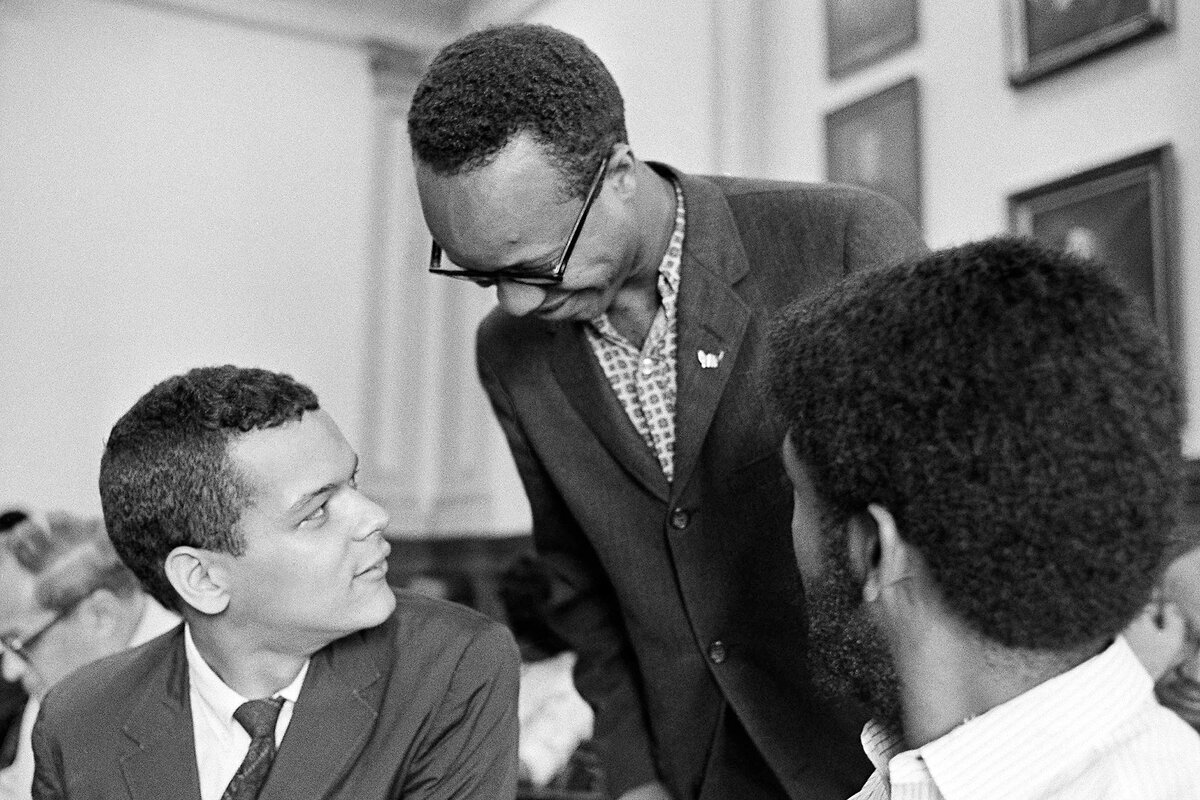

I spoke with Mr. Young professionally on two occasions – the last time in October 2022, when I had him on my podcast to discuss the life of Charles Sherrod, an organizer of the Albany Movement and one of the founding fathers of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The first time was in response to an article in The New York Times about the effect of the coronavirus in Albany, with a headline that read that the pandemic “hit like a bomb.”

The news of Mr. Young’s passing left a hole in my heart. It was only a year or so ago that he spoke honorably of Mr. Sherrod as one of the ancestors. I never thought he would be joining them so soon.

“Reverend Sherrod was like an uncle to me,” Mr. Young said then. “He really didn’t take to the ‘Reverend’ title, so we would just call him ‘Sherrod.’ He was funny and always had a big, bright smile.

“That’s how he was able to pull young people [into the movement], despite some of the parents … and more conservative Black folks who didn’t want this stirring up of trouble,” he added.

The Albany Movement lasted from 1961 to 1962, and was considered a failure by some because Martin Luther King Jr. and others were not able to secure profound gains in desegregation policy. However, not only did the movement sharpen Dr. King’s resolve for future campaigns, it also inspired the locals to push forward. Among those was another unsung civil rights icon, singer Bernice Johnson Reagon, who died in July.

“They kept that movement going and [turned] it into political power,” Mr. Young said. “Long before a lot of places got Black representation in politics, Albany had that in the early ’70s on the heels of the Civil Rights movement.”

In later years, it warmed my heart to see Mr. Young associated with modern-day, Georgia-based movements such as Fair Fight and Black Voters Matter. Such initiatives, in many ways, had evolved from the founders of the Albany Movement.

“Reverend Sherrod’s legacy is integral because he was a chief organizer, and if you’re in these spaces now, you know community organizing is a career now,” Mr. Young told me in 2022. “Even the groups that Stacey Abrams started with Fair Fight and New Georgia Project … those basically stemmed from the work that Charles Sherrod and others like him did.”

Turning the rhetoric of failure into generations of success is modeled by both Mr. Carter and the Albany Movement. When Mr. Carter lost out on his reelection bid to Ronald Reagan, it was seen as an indictment of his ability to lead. In actuality, it allowed Mr. Carter to bloom beyond the walls of the White House and into a decadeslong career of what it means to be a humanitarian. In turn, Mr. Carter was beloved by Black Georgians even before his presidential career for gestures such as selecting African American educator Lucy Lainey’s portrait to be displayed in the Georgia state capitol. President Carter also appointed 40 Black women judges during his tenure – a record that lasted for decades.

And yet, this modest corner of southwest Georgia doesn’t reverberate time and time again because of optics or mere notions of representation. It impacts the world because of its attention toward the needs of everyday people. President Carter’s roots as a peanut farmer from Plains are well-documented, and even the name of his hometown suggests simplicity and commonality. I playfully called Demetrius Young “The Prince of Albany,” and from birth to his matriculation at historically Black institution Albany State University, he was fully entrenched in his community.

Both men remind me that a number of great stories start from humble beginnings, but extending that grace throughout one’s life can make you larger than life.