JFK assassination: three feuds in Dallas

Loading...

| Washington

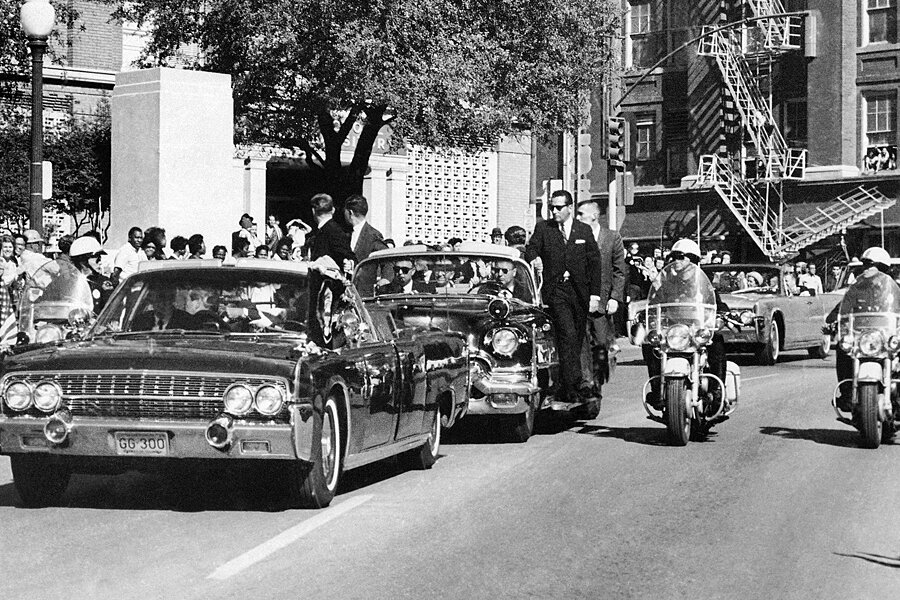

President John F. Kennedy’s trip to Dallas in November 1963 was born in political disharmony. One of his main goals in Texas was to heal a Democratic Party split in the state, which he felt threatened his reelection prospects. He’d won there by an eyelash in 1960, despite the presence of Texan VP Lyndon Johnson on the ticket. If Texas Democrats weren’t all pulling together for 1964, Kennedy might well lose its precious Electoral College votes.

But the party split wasn’t the only political feud present as a subtext in Dallas those fateful days. Here are some of the main crosscurrents, as described by those who lived them in oral histories collected by the Kennedy library and posted online for the 50th anniversary of JFK’s death.

Connally versus Yarborough. This was the main event. Gov. John Connally and Sen. Ralph Yarborough represented two warring factions of Texas Democrats. Kennedy wanted them to make peace. Johnson thought prospects for this were doubtful.

“It was just, perhaps just as simple as the fact that John was a good deal more conservative and Yarborough was a good deal more liberal, and their chemistries just didn’t mix,” said Lady Bird Johnson in 1979.

LBJ had close ties to Connally, who had worked for him, despite the fact that he was philosophically more inclined toward Yarborough’s political positions. Still, Yarborough tried to shun him. He refused to ride in his assigned seat in Johnson’s car in the initial Texas motorcades. Kennedy eventually lost patience and ordered his aides to basically throw Yarborough into the VP’s car if necessary.

That’s pretty much what happened on the morning of Nov. 22. Trusted Kennedy aide Larry O’Brien strong-armed Yarborough into a seat next to LBJ for a motorcade from Fort Worth to the airport, from where the presidential party would fly to Dallas.

“They’re watching us you know,” muttered O’Brien to the senator, indicating the press gathered to see the motorcade assemble. “This is their big story.”

That worked.

Connally, for his part, tried to keep Yarborough as physically distant as possible. When the governor couldn’t shut the senator out of public lunches and breakfasts arranged for the Kennedy visit, he tried to set up two-tier head tables, with Yarborough relegated to the lower level.

Connally was riding in the car with Kennedy in Dallas and was seriously wounded by the first bullet after it passed through JFK’s body.

Appointed secretary of the Treasury by President Nixon in 1971, Connally switched parties in 1973 to become a Republican.

Yarborough was reelected to the Senate in 1964, but defeated in the Democratic primary in 1970 by former congressman Lloyd Bentsen, who ran to his right.

Democrats versus Republicans. Dallas was home to many virulently anti-Kennedy Republicans. On the morning of Nov. 22, The Dallas Morning News ran a full-page ad that purported to welcome Kennedy to the city but then accused him of persecuting anti-communist Cubans, selling food to communist soldiers who were killing Americans in Vietnam, and permitting his brother Robert F. Kennedy, the attorney general, of going soft on “Communists, fellow-travelers, and ultra-leftists in America.”

Appropriately, the ad was bordered in black.

In this context, many loyal Democrats weren’t happy about JFK’s Texas schedule, according to Jeb Byrne, a former reporter who was a General Services Administration appointee serving as an advance man for the trip. They wondered why so much of the president’s time seemed to be dedicated to meeting people who were his political opponents.

They pointed in particular to an event the morning of Nov. 22: a breakfast in Fort Worth hosted by the local chamber of commerce.

“The Democratic Party people were rather put out that the chamber of commerce was going to be the sponsor, which they pointed out was probably Republican-dominated, and that the rank-and-file Democrats were not going to get a chance to see and hear the president. The labor people were vociferous on this point,” said Byrne in a 1969 oral history.

Byrne ended up controlling about 550 out of the 2,200 tickets for the event, and he funneled them to Democratic loyalists as much as he could, including representatives of the local African-American and Hispanic communities.

Partly in response to this Democratic unrest, the administration added an event: an outdoor speech by Kennedy in front of his Fort Worth hotel on the morning of Nov. 22, just before the chamber of commerce breakfast. In a light drizzle, refusing a raincoat, JFK climbed onto the back of a flatbed. The crowd was large and enthusiastic, many union members. They called for Jackie: Kennedy pointed to the window of his room and said, smiling, “Mrs. Kennedy is organizing herself.”

“We are going forward!” Kennedy cried as the union people whistled and stamped. It was his last speech before committed supporters; the chamber of commerce breakfast shortly afterward was the last time JFK spoke in public.

Lyndon Johnson versus Kennedy loyalists. It was no secret that Johnson’s political fortunes were declining prior to Nov. 22. Kennedy himself treated the VP with deference, but there was no missing the fact that LBJ was left out of crucial meetings, including those about the upcoming 1964 campaign.

Some thought that Johnson would be dropped from the ticket. Historian Thurston Clarke writes in “JFK’s Last Hundred Days” that Kennedy told his secretary Evelyn Lincoln that he wanted North Carolina Gov. Terry Sanford as his running mate.

Kennedy aides privately thought LBJ bombastic and unreliable. He thought them dilettantes who did not understand how Congress worked.

“He did feel that there was some dislike, some withdrawal on the part of [Kennedy’s] staff toward him, Lyndon,” Lady Bird Johnson said in 1979. “It was a pebble in a shoe.”

Then Kennedy’s tragic death made Johnson president in a moment. The shoe was on the other foot. As he rose to power in the chaotic afternoon of Nov. 22, Johnson inevitably clashed with distraught Kennedy loyalists.

One of the staunchest of these loyalists was Godfrey McHugh. McHugh was an Air Force general and Kennedy’s Air Force aide from 1961 onward. A debonair figure who spoke French fluently and as a young major dated future first lady Jacqueline Bouvier, McHugh revered JFK.

On the afternoon of Nov. 22, in full uniform, McHugh physically pushed aside Texas authorities at Parkland Hospital who were trying to prevent Kennedy’s body from being flown out of the state and back to Washington. He rode in an ambulance with the first lady and the casket to Air Force One. Once they had arrived, he felt the plane should immediately take off from Dallas’s Love Field. That was protocol. Jackie Kennedy told him she wanted to depart.

“So I got up and went through the airplane to the crew and told them, ‘Let’s leave, now that the president is aboard’ ... and walked back. Nothing happened,” McHugh said in a 1978 oral history.

McHugh became increasingly agitated as the plane remained on the ground. He tried again to order the plane to take off. Pilot Col. James Swindal, McHugh’s nominal subordinate, refused.

“He said, ‘The president wants to remain in this area.’ I said, ‘The president is in the back,’ ” McHugh remembered.

The pilot was referring to Johnson, who unbeknown to McHugh was on board the plane and waiting to be sworn in, though he had acceded to the presidency at the moment of Kennedy’s death.

McHugh was referring to Kennedy’s body. Like many loyalists, JFK remained a vibrant presence in his mind, the true US chief executive. At the widow’s request, he stood guard over the casket until Air Force One arrived at Andrews Air Force Base at 6 p.m., Eastern Standard Time.