Plastic guns bill: Is Congress overlooking a fatal flaw?

Loading...

| Washington

Among the issues that trigger temblors in America’s gun debate, a federal law that bans undetectable plastic firearms has not been considered an earth-shaker.

But that was before the invention of 3-D printing technology that allows an individual to make a gun at home. That technological advance is now causing a noticeable tremor in Congress.

On Tuesday, the House reauthorized the Undetectable Firearms Act, which regulates plastic guns, in a voice vote. The Senate is expected to take up the issue when it returns from its Thanksgiving recess on Dec. 9. Yet some in Congress are already saying that the rise of 3-D technology means the law is outdated and will have to be amended soon.

Extending the law “doesn’t mean you can’t come back and say, ‘Given the advances of technology, it’s time to update this law,’ ” says Brian Malte of the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence.

He suggests a thorough review of the law is needed, noting that the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) is “deeply concerned. I think that tells you a lot.”

Some House Democrats agree. But on Wednesday, they joined Republicans in a simple 10-year extension of the law, preferring to extend the law as-is than risk expiration because of a potentially divisive 3-D debate.

Three-dimensional printing wasn’t around in 1988, when Congress passed the law, which makes it illegal to “manufacture, import, sell, shop, deliver, transfer or receive” any gun that can’t be spotted by metal detectors and X-ray machines. But today’s printing technology makes it possible to produce plastic guns that won’t be noticed by a metal detector, and this has the ATF worried.

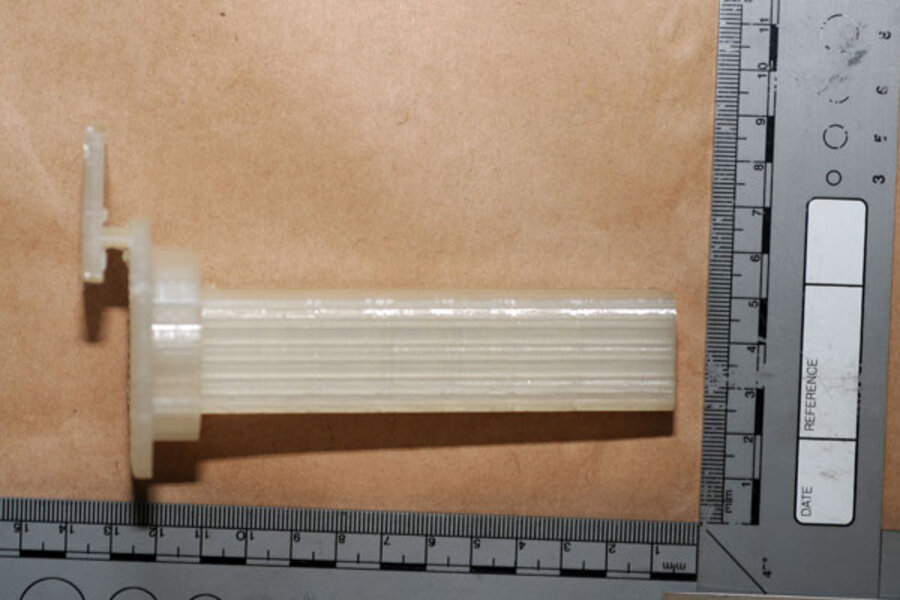

Last month, the ATF made public the tests of some plastic firearms that it produced based on instructions available on the Internet. The results were mixed. One gun exploded when it was tested. But another gun that was made from plastic found in toys and luggage was able to fire all eight times that it was tested, and was described as “lethal” by the ATF.

The ATF guns were made from blueprints uploaded to the web by a group called Defense Distributed. The State Department has told the group to stop uploading its blueprints, but last May, more than 100,000 copies of the plans for the gun, known as The Liberator, were downloaded.

It’s not illegal to make such a gun for personal use (selling or manufacturing would require a federal license). But gun-safety advocates and Democratic lawmakers are particularly worried about the potential misuse of such guns, which is why Democrats have been pushing to “modernize” the Undetectable Firearms Act before it expires on Dec. 9.

These lawmakers want the act to take into account the new 3-D printing process. While the law does require guns to have a certain amount of metal in them, those pieces can be easily removed. An updated version of the act by Rep. Steve Israel (D) of New York requires that plastic guns have metal pieces that are not removable. Some Senate Democrats, such as Charles Schumer of New York, support the idea.

But Republicans and gun manufacturers oppose the update for several reasons:

- Three-dimensional printing of firearms has not posed a danger so far.

- It’s a fairly expensive process that discourages widespread at-home use.

- Airport scanners that require you to put your hands above your head can detect plastic objects even with no metal in them.

- The manufacturing process of plastic guns can’t be stopped and restarted to insert permanent metal pieces, explains Lawrence Keane, senior vice president and general counsel for the National Shooting Sports Foundation Inc., which is the trade association for the ammunition and firearms industry.

“There has never been a single crime committed with one of these objects,” says Mr. Keane. “You don’t see homemade guns recovered at crime scenes today.”

Perhaps not today, but what about tomorrow? Technology moves very quickly, argue advocates of updating the law. What is difficult and costly to produce now, will soon be easy to make – and more lethal, they say.

This issue is unlikely to be resolved in the near future. Neither is it likely to go away.