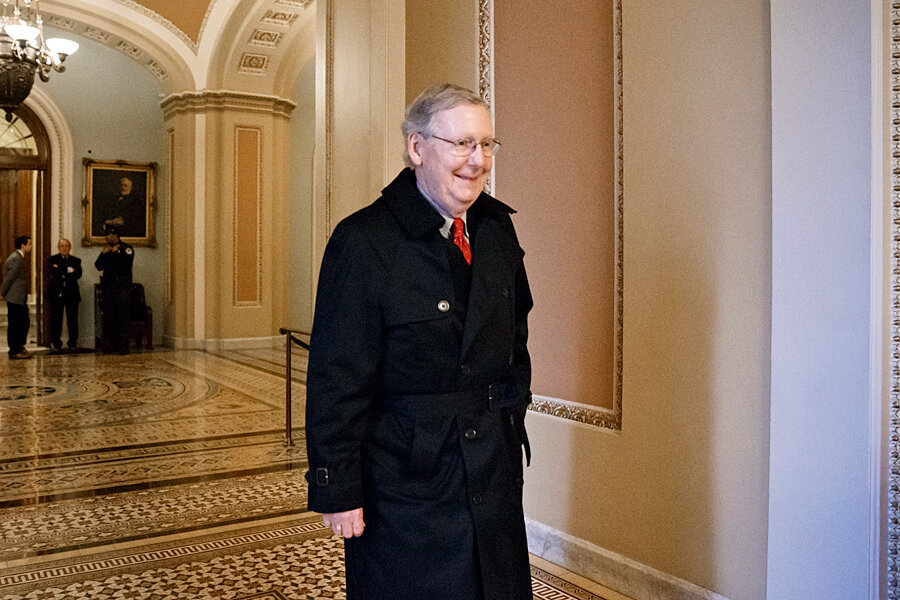

As would-be Senate reformer, Mitch McConnell faces first test with Keystone

| Washington

When Mitch McConnell took over as Senate majority leader, the Republican said that "Step 1” in showing Americans that Washington can work is to get Congress functioning again – and that means “fixing” the Senate. The would-be reformer has his first test in the controversial Keystone XL oil pipeline, which is Topic A in the Senate this week.

The Kentuckian says he wants to use a bipartisan bill that approves the Keystone pipeline to prove that the Senate can return to being a chamber of open debate – one in which both parties have an opportunity to offer amendments; where committees, rather than party leadership, craft legislation; and where priorities are hammered out through the regular budgeting process, all while avoiding a government shutdown.

The ultimate goal is to restore the Senate to its “high purpose,” as Senator McConnell put it, where Republicans and Democrats can work through the big – and more likely, the small – issues of the day.

But Democrats are already pointing to broken promises vis-à-vis procedure on Keystone. They’re alerting media to the infractions and threatening with their own maneuver that could have the Senate taking an important procedural vote around midnight Tuesday. More hurdles lie ahead as Democrats promise to file amendments.

The maneuvering is a sign of how closely McConnell will be watched, and shows how difficult it could be to pull this reform off at such a polarized time in US politics. Still, those who know the leader say that if anyone can follow through on reform, it is the man who has been preparing for this job for most of his adult life. Indeed, he has proved himself as a reformer earlier in his career.

“I doubt if there has ever been a majority leader who has prepared himself better for the post in terms of reading history and learning from the past,” says Keith Runyon, a journalist in Louisville, Ky., who worked for The Courier-Journal for 43 years. “There have been times in his life when he has been a very impressive reformer.”

Mr. Runyon points to McConnell’s first elected position in public office: his 1977 election to the leadership post of judge executive of Jefferson County, which includes Louisville. He unseated incumbent Todd Hollenbach, a Democrat who had “come under fire for running a crony-laden, ethically challenged administration,” according to Alec MacGillis, in his McConnell biography, “The Cynic.”

The young McConnell – a moderate Republican who supported abortion rights and conservation and promised (but didn’t deliver) collective bargaining for public employees – cleaned house. He installed competent public servants who were in it for neither gain nor spoils, according to Runyon. He brought in a bipartisan administration. He worked together with the Democratic mayor of Louisville to merge the city and county governments, an endeavor that didn’t bear fruit until after McConnell became a US senator.

The Jefferson County “legislature” – a Democrat-controlled commission – posed a particular challenge for the young executive, according to David Huber, who was a student at the University of Louisville with McConnell and later joined him in county government. Even getting the commission’s approval for certain high-level county hires became a slog for McConnell.

So the Republican went to one of the Democratic commissioners, Sylvia Watson, to see if he could build a working relationship and find an ally, according to Mr. Huber. She represented much of the eastern part of the county, which was more conservative and was where McConnell had gotten much of his support in the election. Also, Ms. Watson wasn’t a strongly partisan Democrat.

“I know they had some kind of mutual admiration. She would come to his office a lot. I would sit in on the meetings. They talked candidly about what they wanted to get done and what he wanted to do. She was an invaluable ally,” Huber said. “We couldn’t [get things done] without her.”

That dynamic is sort of like the GOP’s outreach to Democrats on Keystone. On Monday, 10 moderate Senate Democrats plus an independent helped clear a 60-vote procedural threshold on the bipartisan Keystone bill. McConnell will need even more such collaborators if he wants to reach the magic number of 67 – enough to overcome a promised presidential veto. The prospect of a veto is one reason for McConnell considering Democratic amendments now, to help build veto-proof support for the bill – although it’s highly unlikely he can find 67 votes.

As judge executive, “Mitch promoted honest and good government. Quaint sounding terms today, but they were vibrant in 1977, and with some of us, still ring true. That is why I have great confidence that Mitch can rise above the malaise in Washington,” writes Runyon in a follow-up email.

Few people question McConnell’s desire to reform the Senate. As he started his sixth term as senator last week, he spoke of the body with affection, calling it the “the Senate we love.”

No one questions his perseverance, a quality that McConnell says he learned from his mother, who spent two years giving him daily physical therapy and keeping him off his feet as a small boy struggling with polio.

“He’s absolutely committed” to restoring the Senate to a more open, collaborative body, says Sen. Bob Corker (R) of Tennessee, now chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Neither does anyone doubt his knowledge of the institution, or his parliamentary skill. He often invokes his legislative hero – the 19th-century Kentucky statesman and senator, Henry Clay, who was known as the “great compromiser” for the difficult deals he negotiated to stave off civil war. Clay’s portrait hangs in the leader’s Senate office. A more contemporary favorite is the longest-serving majority leader, Democrat Mike Mansfield of Montana, who treated every senator “as an equal,” as McConnell put it in a speech a year ago.

But Sarah Binder, a congressional expert at the Brookings Institution in Washington, brings that happy talk down to earth. “The Mansfield Senate of the 1970s doesn’t look anything like the partisan Senate” of today, she says. “It’s going to be very tough for McConnell to tone down the procedural arms race ... that’s been going on for 10, 20 years,” she says.

Democrats well remember McConnell’s obstructionist tactics, his stated priority to deny President Obama a second term, and his conservative ideology. Pointedly, he talks about a “right of center” mandate – not a center-right one. Expect the majority leader to always pursue the most conservative position possible, even if not the most conservative one imaginable.

While McConnell spoke about the need to “work together” in his opening speech last week, he also lashed out at the president. Washington Post columnist Dana Milbank described it as a “bitter” speech and mocked the Senate leader for giving credit to the Republican takeover of Congress for an improved economy. The press secretary for Senate minority leader Harry Reid (D) of Nevada repeated those criticisms, as did other Democrats.

Let’s say, though, that in the coming months the famed McConnell fortitude carries the day and that the Senate turns back the pages of history to a more respectful, workmanlike time. Even so, he’s not the only factor in the equation of Washington government.

There’s also the House – yes, controlled by Speaker John Boehner (R) of Ohio, but challenged by a hornet’s nest of hard-liners. In a historic rejection, 25 of them turned against Representative Boehner in his bid for the speakership last week, though that wasn’t enough to deny him the job. Still, they will make his life very difficult, and that will make it hard to harmonize with the Senate, where Democrats can filibuster what the House sends over.

There’s also the president, who last week issued two veto threats on bills working their way through the new GOP majority on the Hill, including Keystone.

“There’s going to have to be a three-way partnership if this Congress is successful. That’s going to have to be McConnell, Boehner, and President Obama,” says Ray Smock, a former House historian now at Shepherd University in Shepherdstown, W.Va.

McConnell has his work cut out for him in “fixing” the Senate. Fixing Washington is another thing entirely.

• Ryan Alessi in Murray, Ky., contributed to this report.