How FDR put his stamp on 'day of infamy' speech after Pearl Harbor

Loading...

December 7, 1941, was the day of infamy – the date when the Japanese hit Pearl Harbor with a surprise attack. But December 8, 1941, was the day of “infamy” – the date when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in a joint session of Congress spoke the famous line that helped rally the nation and defined the event for generations of Americans to come.

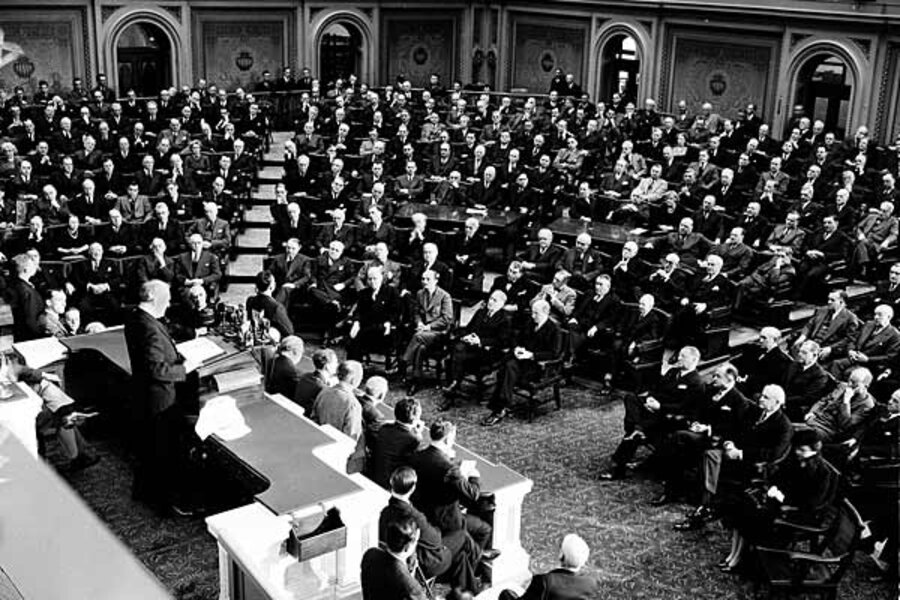

It was the very first line of his speech to the hushed assembled lawmakers. Gripping the podium in front of him, at about 12:30 PM on the day after the attack, FDR said this: “Mr. Vice President, Mr. Speaker, members of the Senate, and of the House of Representatives, yesterday, December 7, 1941, a date which will live in infamy, the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.”

The effect was electrifying. The whole speech was short, only six minutes or so, and intended to convey an emotional jolt to the American people. Secretary of State Cordell Hull had argued for a longer address laying out the recent history of US-Japanese diplomatic negotiations, but the president rejected him. His aim was to unify the country, not explain the US position to the world.

You can see that in FDR’s notations on the first draft of the speech, posted online by the FDR presidential library [PDF]. The draft itself had been dictated to FDR’s secretary Grace Tully at about 5 PM on December 7. It began, “Yesterday, December 7, 1941, a date which will live in world history....“ But FDR scratched “world history” out with his pen, and printed over it in a spidery hand, the single word “infamy.”

Yes, the word which defined the speech itself was a last-minute addition. FDR also added by hand another of the speech’s famous impact lines: “No matter how long it may take us to overcome this premeditated invasion, the American people in their righteous might will win through to absolute victory.”

Thirty-three minutes after Roosevelt finished speaking, Congress voted to declare war on Japan. Only one lawmaker, Rep. Jeannette Rankin (R) of Montana, voted “no.” She was a lifelong pacifist who had also voted against the US entry into World War I.

The speech was broadcast live on radio, and heard in an astounding 81 percent of American households.

One long-standing mystery surrounding the address was the whereabouts of the final draft – the reading copy FDR placed on the podium in front of him. When he returned to the White House, FDR did not give the copy to Grace Tully to file. No one could find it for 43 years.

Then in March 1984, a National Archives employee found the copy in the records of the US Senate, Record Group 46. FDR evidently left it behind in the House chamber, where the address took place. A Senate clerk retrieved it, wrote on it “Dec. 8,1941, Read in joint session”, and filed it away for the ages.