Nuclear threat: ubiquitous in 1960s, absent from 2016 race

One of my earliest childhood memories involves thermonuclear war. That memory is over 53 years old, which helps explain something important about the current presidential campaign.

On October 22, 1962, President Kennedy went on national television with a startling revelation about the Soviet Union’s military buildup in Cuba: “[A] series of offensive missile sites is now in preparation on that imprisoned island. The purpose of these bases can be none other than to provide a nuclear strike capability against the Western Hemisphere.”

Kennedy announced a naval blockade and warned that he would regard any missile launched from Cuba “as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.” It was obvious that “a full retaliatory response” could mean only one thing: World War III.

Even children knew that something was up. I was in the second grade at St. Clement’s Grade School in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. Like schools all over the country, St. Clement’s made students wear name tags and go through air-raid drills. As a seven-year-old science nerd, I already understood that marching into the corridor and hiding under our coats would do us no good in the event of a nuclear attack. I remember how scary it was to hear a test of the local civil-defense siren. The next time the siren blared, I realized, the missiles might be on their way.

Though JFK eventually resolved the crisis, it left an impression on Americans young and old. Several months later, Gallup found that 89 percent thought that their chances of surviving an all-out nuclear war were no better than 50-50. Movies such as Dr. Strangelove and Fail-Safe reflected this widespread apprehension.

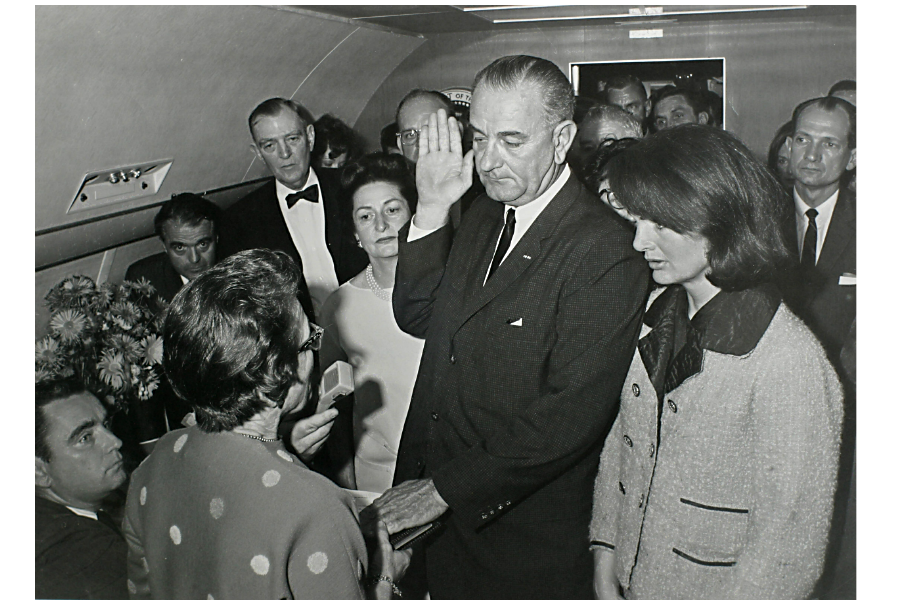

The crisis reminded Americans that their very existence could hinge on the president’s knowledge and judgment. The GOP candidate for president in 1964 was Senator Barry Goldwater. Though Goldwater had expertise in national security, he had made careless statements, such as his joke that he wanted to lob a nuclear bomb “into the men's room of the Kremlin.” Democrats could thus paint him as a dangerous extremist. They aired what would become the most famous campaign ad in political history. “The Daisy Spot” juxtaposed a little girl counting flower petals with the countdown to a nuclear explosion. “Vote for President Johnson on November 3,” said the tag line, ‘The stakes are too high for you to stay home.”

For years to come, presidential campaigns would keep returning to the nuclear trigger. A 1968 Nixon ad asked: “Think about it - when the decisions of one man can affect the future of your family for generations to come, what kind of a man do you want making those decisions?” It ended with the text: “THIS TIME VOTE LIKE YOUR WHOLE WORLD DEPENDED ON IT.” As late as the 1984 Democratic primaries, former vice president Walter Mondale was making the same case with an ad showing a symbolic red phone: “The most awesome, powerful responsibility in the world lies in the hand that picks up this phone. The idea of an unsure, unsteady, untested hand is something to really think about. This is the issue of our times … vote as if the future of the world is at stake.”

That was 32 years ago. Since then, the end of the cold war and the passage of time have shifted the threat of nuclear war to a distant corner of the public mind. This change works to the advantage of Donald Trump. His response to a debate question showed that he did not even understand the term “nuclear triad” (strategic bombers, intercontinental ballistic missiles, and submarine-launched ballistic missiles). More recently, he appeared to advocate nuclear proliferation, which would greatly increase the chances of nuclear war. During the 1960s, voters would have seen such comments as disqualifying. Nowadays, they shrug.

They shouldn’t. The United States and Russia still have thousands of nuclear weapons. General Mark Milley, the Army’s Chief of Staff, said at his confirmation hearing that Russia is “the only country on Earth that retains a nuclear capability to destroy the United States, so it's an existential threat to the United States.” Former Defense Secretary William Perry writes that “the risk of a nuclear catastrophe today is greater than it was during the Cold War.”

The current campaign would be unfolding quite differently if Americans took such comments to heart and voted as if their whole world depended on it.

Jack Pitney writes his "Looking for Trouble" blog exclusively for Politics Voices.