How a group of California teens won a national science bowl

Loading...

| santa monica, calif.

Ingo Gaida's classroom at Santa Monica High School is striking on two counts: First, for a biology class, it is remarkably devoid of life-forms, with the sole exception of a pint-sized goldfish named "Beast 6." Second, the air is filled with the drone of constant questions – imagine Gregorian monks chanting in a quiz show cadence – and the rapid-fire response by eight students all clutching their pedagogical tool of choice: a buzzer.

And the questions are hard, really hard, although the students respond with fiber-optic quickness, usually well before the query is half uttered.

At this point, a realization is in order: The interrogator and these eight students are the life-form in this room. They comprise a cauldron of intellectual fervor – like one of those superheated sea vents occasionally discovered in the dark reaches of the ocean where creatures grow to unheard of lengths and live on minerals believed too rich to sustain life – the chemistry, biology, and ichthyology which these students could tell you about in considerable detail.

This is "Aca-deca," short for the Academic Decathlon class. Here, 30 of the best and brightest high school students in this California beach community prepare for national quiz competitions. Part crucible and part gauntlet, this is where the student teams are formed, tested, and toughened. It's the equivalent of intellectual "two-a-days."

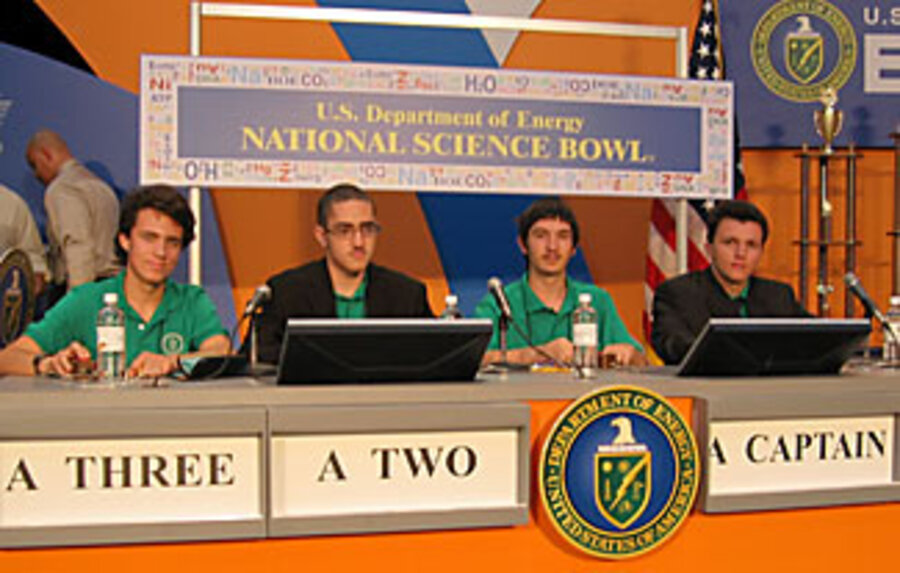

Students prepare all year for three contests – one in general knowledge, one in science, and one on oceans. This year, for the first time since Mr. Gaida launched the class nine years ago, a Santa Monica team won first place in one of the contests – becoming national champions of the US Department of Energy's National Science Bowl. "The last three minutes of the final game were the longest three minutes of my life," says Gaida. "It's so hard to win this competition."

• • •

Gaida is a tall, balding Advanced Placement biology teacher and native Californian who neither looks nor sounds like the legendary football coach Bear Bryant. Nevertheless, there are similarities. He has hand-selected his class based on results from grueling tryouts held each fall. The workouts include an arduous test on a fact-laced article chosen for its sheer monotony.

"It indicates whether a kid is willing to work on tough material," says Gaida, sounding like a didactic drill sergeant.

Comprised of roughly equal numbers of ninth through 12th graders, the quiz class is not for the feint of heart or mind. Students are expected to digest libraries of knowledge every three weeks. Things like the name of the medieval warriors outlawed in the Icelandic legal code known as the Grágás (Beserkers). Or, most often, science facts such as the stoichiometric coefficients for nitrogen, hydrogen, and ammonia in the balanced reaction for the Haber process (1, 3 & 2 respectively, if you must know).

They will be expected to recite the answers, accurately, in an Alex Trebek second. They are expected not to flinch, no matter what the pressure or how many people are watching. And it helps if they find the whole thing enjoyable.

"It's fun to compete," says Dimitry Petrenko, 18, the square-shouldered geology specialist. Then he gets more to the point: "I like to win."

He speaks from experience – he is a member of the championship team. Alexandre "Sasha" Boulgakov, Ian Scheffler, and Marino Di Franco are the other three. Although their days as a team are over – three are seniors and moving on – it is apparent they still function as a unit. In an interview, they tag team on stories, amplifying each others' thoughts and frequently clarifying statements for caliper accuracy.

Each was responsible for one particular field, such as biology or math, but the strategic responsibilities extend beyond mere knowledge. The early rounds of a match have supposedly "easier" questions. These were the bailiwick of Petrenko, who also competes in judo (he likes to win there, too). He brings martial arts reflexes to the buzzer, beating opponents with quickness. "If two players have the same knowledge, Dimitry always wins," says Boulgakov.

Later rounds fell to Boulgakov and Di Franco, two of the best math and chemistry students in the nation. "They're superstars. It's like Kobe Bryant and LeBron James," says Scheffler. He then turns to his fellow teammates and says, "You know who those guys are now because I pointed them out, right?"

Boulgakov and Di Franco pause significantly longer than they need to remember stoichiometric coefficients, before nodding yes.

Scheffler is the only team member who is a native southern Californian (the others are from Russia and Venezuela). He's also the only one who tie-dyed his prom shirt, a process for which he provides the precise chemical explanation.

For all the knowledge these four carry around, no two had the same approach to learning. Boulgakov finds Wikipedia a paradise of limitless links. Scheffler made flashcards from Gaida's infamous packets – concentrated compendiums of names, dates, and concepts. He has more than 11 pounds of them sitting in his closet. Di Franco has taken nearly a dozen college courses, three of them in computers. Petrenko studied the old-fashioned way – with textbooks.

"I think computers are voodoo," he says.

"They're very self-motivated," says Gaida of team members, "and all pretty curious."

Curiosity has occasionally gotten the better of them. One day, Di Franco decided to synthesize thermite, a metallic compound used in welding, which ignited a purple fire and forced the evacuation of the school. He is still able to point out the scorch marks on the ceiling, though nothing in the room actually caught on fire. The compounds necessary for the experiment have since been locked away. "I had heard about its color," he says. "I just wanted to see it for myself."

• • •

Team members look like your typical teenager: cargo pants and T-shirts, shorts and sneakers. No surfers in this crowd but neither are they nerds: Several like heavy metal music. The big difference is that they all spend a little more time with books, and, significantly, seem to retain what they read.

In the National Science Bowl finals, the Santa Monica squad prevailed over 66 other teams, each of which was a victor in regional competitions that involved a total of 12,000 students. The team won a six-foot trophy, $1,000 for the school, and a trip to London. Additional benefits come with being cerebral, too. "Girls like science bowl champions," says Petrenko with a sly smile.

The equation works the other way, too – science bowl champions like girls, as Di Franco notes – but only the smart ones. "There's no denying that it's hard to associate with some girls when you think what's entertaining is a book called 'The Nature of Solids,' " he says.

Di Franco has another year left in high school, but the others are all going on to college – some of the best in the country, not surprisingly. Despite being nearly always precise, when they discuss what the future holds, all four drift to generalities: lab research, computer science, becoming a doctor. "Dimitry has a dream of getting an island," mentions Di Franco.

In talking about them and his other students, Gaida also backs away from specifics and any prediction of Nobel prizes. Using the cautious language of a scientist, he says only that, "They will all be tops in their fields somehow."

With the school year winding down, and the competitions behind them, perhaps all that's necessary for now is to relax. But this may not be in their nature, as Petrenko states with a characteristic restlessness.

"Now that it's over," he says, "I'm bored."