Police and blacks: old tensions slow to heal

Loading...

| Atlanta

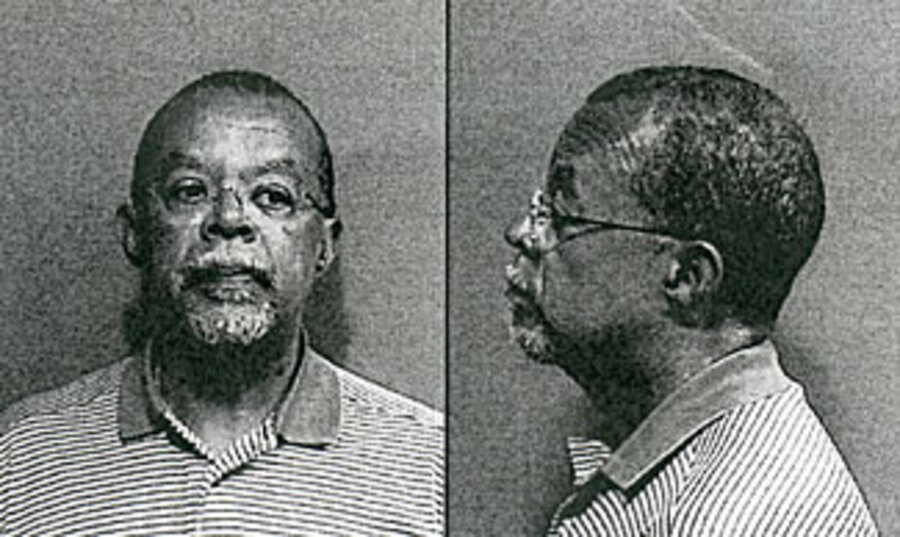

President Obama sent a stern message to America's 800,000 police officers Wednesday when he said that police in Cambridge, Mass., acted "stupidly" for arresting his friend, black Harvard scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr.

The remark is likely to anger many men and women in blue, especially since the arresting officer, Sgt. James Crowley, has refused to apologize and told The Boston Globe, "I am not a racist."

But the remark also hits on what John McWhorter, a scholar at the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, calls the last true barrier to a "post-racial" America: poor relations between blacks and police.

Last Thursday, Crowley arrested Professor Gates, who was returning from a trip, after the author of "Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Man" became "tumultuous," according to the police report, and accused Crowley of racial profiling for demanding to see identification. Gates, the police report says, confronted the officer's request by saying, "Why, because I'm a black man in America?"

A neighbor had called police to report an attempted burglary by two black men. It turned out to be Gates and his driver trying to open a jammed door to Gates's house. Police said that cooler heads on both sides did not prevail, and the charges were dropped on Tuesday. Gates demanded an apology from Crowley. Crowley said Thursday he'll "never apologize."

Cambridge's Police Review and Advisory Board, an independent body, has a meeting set for July 29 to review the case.

On Wednesday, Obama waded in at the end of a long presentation on healthcare reform. He drew praise from many who thought he called the situation as he saw it, but he also risked criticism not only from police officers, but from the Secret Service, who might take umbrage at his joke that if he were trying to jimmy his way into the White House, "I'd get shot."

Speaking on Boston's WEEI radio station Thursday, Crowley refused to criticize Obama directly for his statement. But he added, "It's regrettable that anybody on either side of this issue would make comments ... without talking to those who were there ... and who saw themselves the way in which Professor Gates acted and what led to his arrest."

Because of black experiences going back to slavery and through the Jim Crow days and beyond the busing protests of the 1970s, many blacks – both rich and poor – feel like a persecuted class, especially when it comes to relations with the police.

"For black men, these things happen frequently. And this moment [involving Gates] – which is so charged and extreme and shows what can happen even to a top intellectual in this country – can be a way toward bridging some of these divisions [between blacks and law enforcement] and increasing awareness," says Prof. Patricia Sullivan, a former colleague of Gates's and author of "Lift Every Voice," a recently released history of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). "Yes, we've had tremendous gains, but there are so many areas where race remains a factor and part of our reality."

Still, police are in a difficult position: Crime rates tend to be higher in minority communities.

Yet the vast majority of police departments today are representative of the communities they serve in terms of race and ethnicity, says Jim Pasco, executive director of the legislative division for the Fraternal Order of Police, a national union. US policing, he says, "is ahead of the general population in terms of awareness to sensitivities within the community, and we're painfully aware of that because of our own experience and our mistakes of the past."

Mr. Pasco says that "Sharptonesque" statements from Gates and the off-the-cuff remark by Obama will not help street relations, but will drive a deeper wedge between law enforcement and minorities.

-----

Follow us on Twitter.