Mosque debate: Behind America's anxiety over Islam

| New York

As the maelstrom over the proposed Islamic center near ground zero rages a short distance away, Shahid Farooqi, a devout Pakistani immigrant, is handing out book bags and school supplies to hundreds of needy children and their parents for the start of the school year. It's Ramadan, the most holy month on the Islamic calendar, and Mr. Farooqi is volunteering his time with the Islamic Circle of North America, a grass-roots organization devoted to establishing a place for Muslims in America.

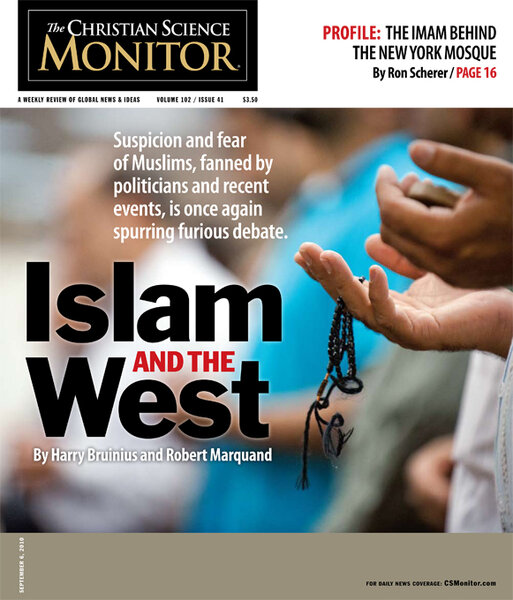

The charitable giveaway is the religious group's first event here at an undeveloped lot in Midwood, a neighborhood in Brooklyn often referred to as "Little Pakistan," where it plans to build a youth center. Farooqi and others are dressed in classic American volunteer attire – yellow T-shirts emblazoned with a logo – but the men also wear topi skullcaps and the women observe hijab, covering their hair and necks with scarves. The volunteers are well aware that a 15-minute subway ride away, hundreds of protesters, many carrying US flags, are marching through the streets of Manhattan near the site of a much larger proposed community center, chanting, "No mosque here! No mosque here!"

"When you have certain beliefs, of course not everyone is going to be happy with you," says Farooqi, a history teacher who lives in Queens with his wife and four children. "But regardless of people finding and putting labels on us, still, we have to do good work, and we have to face those challenges ... and we believe that once we continue doing this, we're going to make our home here, in this society...."

In many ways, Farooqi's experience of making a home in New York represents a profound trajectory in American religious history: New groups have immigrated to the US over the centuries, bringing unfamiliar religious practices, and a host of new religious ideas has sprung up from within the fertile soil that freedom brings. And these have always sparked unease and even public resistance from those who hold more established ways of understanding God.

Today, however, the vortex of discord sweeping over the country has exposed a deep-seated mistrust, if not outright phobia, of Muslims trying to establish a place in America. While this may be a predictable historical pattern as Islam becomes more visible in American communities, it has also laid bare a country struggling to balance its deeply held values of religious freedom and tolerance with its fears, real and imagined, in an era of terrorism.

Trauma and anger still linger over the World Trade Center's unprecedented destruction.

Families still publicly grieve the loss of their loved ones. Incidents like the Fort Hood, Texas, shooting and the thwarted Times Square bombing in New York City reinforce fears of home-grown terrorism. "The symbolism is so fraught with meaning," says Douglas Hicks, a religious scholar at the University of Richmond's Jepson School of Leadership Studies in Virginia. "There is no more symbolically loaded space in America today than ground zero. Then you mix in religion, and the 'T' word – terrorism – and you get this explosive, unholy mix."

From the start of the controversy this May, the symbolism of a "mosque" invading a "sacred" American space has dominated the visceral reactions of many opponents. Critics call the proposed center a "slap in the face" and a "monument to terrorism" and an act of "arrogance and insensitivity." Indeed, the debate has centered on what President Obama called the "wisdom" of building such a center so close to what people feel is sacred ground. Build it, but not here, has been a common refrain.

As Charles Smith, a drywall hanger and painter from Queens who attended the recent protests against the Muslim center, puts it: "I keep hearing, yes, they have a constitutional right, they have a right to build it there. But they don't have to be offensive. If it's offending 70 percent of people in the United States, say, 'No, it's offensive to them, so we'll go somewhere else.' "

Still, the controversy has kicked up sentiment that runs much deeper than the appropriate location of a mosque. Rightly or wrongly, more and more people have been willing to equate Islam itself with an oppressive, terrorist ideology, incompatible with American norms and laws. While the visible presence of Islam so close to ground zero has fomented the most anger, ricocheting from Manhattan to the megaphone of the Internet to the midterm elections, other proposed mosques – near far less hallowed ground – have also encountered sometimes violent opposition in townships from Tennessee to Wisconsin to California.

A recent Gallup poll found that 43 percent of Americans admitted to feeling at least "a little" prejudice against Muslims, and the Pew Research Center has reported that 35 percent feel Islam is more likely to encourage violence than other faiths. Even so, Pew also found the estimated 2.4 million Muslims living in America to be solidly middle class and mainstream, with incomes and education levels mirroring the general public – unlike their more prevalent working-class counterparts in Western Europe. This is one reason, observers say, there are very few radical mosques in the US.

As the controversy over the proposed Islamic center rages on, however, some Muslim groups worry about increased discrimination and violence. "The fear is that Muslims cannot take their place in American life without harassment or subjugation or being seen as being involved with some conspiracy theory," says Ahmed Rehab of the Council on American-Islamic Relations. Though the council does not have exact figures yet, Mr. Rehab says, anecdotally the number of civil rights complaints filed through the council has risen since the "ground zero mosque" began making headlines.

Already, the number of Muslim workplace discrimination complaints filed with the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has been going up – 53 percent in the past three years. In New York, meanwhile, authorities recently charged Michael Enright with attempted second-degree murder and hate crimes for stabbing a Bangladeshi cabdriver after he learned he was Muslim.

Behind the explosive, unholy mix of religion, politics, and tolerance run deep crosscurrents of American social history. Controversy over religious differences sprung up almost immediately with the first settlers, and the American experience with such conflict has helped shape the deep values of religious freedom and tolerance in this country today.

Even in Colonial times, Rhode Island sprang up as an early "baptist" community after Puritan leaders in Massachusetts banished Roger Williams for his version of the Christian faith. Mormons fled to the West and built a thriving community in Utah after an angry mob in Illinois murdered their leader Joseph Smith. Sporadic acts of vandalism plague synagogues to this day.

"Throughout our American history there's been a series of moments when the sense of some kind of established status quo felt [it was] being invaded," says William Lawrence, dean of the Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. "It was true in the late 19th century when the perceived Protestant status quo saw immigrants coming from Roman Catholic countries and upsetting the balance of the culture. The Catholic invasion from Ireland, Italy, and other central European countries was somehow going to alter the Protestant identity of the nation. That was the fear."

The US today again stands on the verge of profound demographic changes. Protestants now make up barely 51 percent of Americans, according to Pew, and the internal diversity and fragmentation of this group almost makes the term meaningless. At the same time, as Latin and Asian populations expand their presence, making non-Protestant and non-Western religious practices even more visible, cultural unease, too, is only expected to increase.

"We've all seen an increase in anxiety in general – with the economic downturn as well as the terrorism threat," says Professor Hicks, who studies the intersection of religion and economics. "So you see people who are more stressed out because of their financial situation, more people with family stresses and cultural anxieties towards anyone who looks different or who appears to be threatening."

Politically, a new rallying cry against sharia, or Islamic law, has begun to galvanize opposition to the presence of any new mosque around the country, if not Muslims themselves.

Former US House Speaker Newt Gingrich, who last month compared the effort to build the Islamic center to Nazis posting signs next to the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., has been outspoken in denouncing "creeping sharia" in the US. He has argued that "radical Islamists" are attempting to use American values of tolerance and freedom of religion to implement sharia law by stealth, which for him includes the practices of honor killings, physical mutilations, and spousal rape.

And though sharia law has a multitude of interpretations within a wide spectrum of Muslim traditions – like any other widespread global faith – a growing number of Americans are identifying the word with the chilling practices of the Taliban, and as representative of all of Islam. One of the most common signs held up by protesters at ground zero has been a one-word sharia in bloodlike letters.

The lack of an informed distinction between the sharia law of radical groups like the Taliban and the religious practices of the vast majority of the world's 1.57 billion Muslims, say observers, only leads to further unease in today's volatile times. "We see a public that is still ignorant of the tenets of the Islamic faith, as practiced by the majority of Muslims," says Robin Lauermann, professor of politics at Messiah College in Grantham, Pa. "It is reinforced by sound bites and stereotypes rather than meaningful education about the faith."

For Farooqi, whose faith does not permit him to shake hands with an unmarried woman, sharia law is more about the five pillars of Islam, which includes almsgiving and helping the poor. "I am a follower of Muhammad, the messenger, peace be upon him. So for me, I want to follow his footsteps, I want to help the poor, because he helped," he says. "This is the basic duty of any human...."