Behind the falling US birthrate: too much student debt to afford kids?

| Los Angeles

Karen Hu of Oakton, Va., is 28, married, graduated from law school – and thinking about babies. But that's as far as she and her husband, a software programmer, have gotten: just thinking. What's holding them back?

For one, Ms. Hu is finding it a challenge to land a good job in the post-recession economy.

For another, her student debt – some $164,000, with a monthly payment of $818 – is forcing the couple to think hard about taking on the additional expenses that come with having a child. "Children just don't fit into that scenario," Hu says.

Multiply that tale by tens of thousands of couples and you get the lowest birthrate in US history. American women of childbearing age are having babies at a rate of 63 per 1,000 women – nearly half the peak rate of the baby boom era of the 1950s, the Pew Research Center reported at the end of 2012.

No surprise, recessions typically coincide with a birthrate dip, as financial uncertainty prompts couples to postpone adding new mouths to feed. But the economy is recovering, and there's no sign yet that the birthrate is rebounding. Some analysts now wonder if the unprecedented scale of early indebtedness stemming from student loans, affecting nearly one-quarter of the overall US populace of childbearing age, has become a permanent deterrent to parenthood.

"This is something that we have not had during earlier recessions," says Chris Christopher, senior economist at IHS Global Insight, an international consulting group. If college costs keep rising and students continue to borrow heavily to pay for their education, the record-low birthrate may become the "new normal," he suggests. "This is a real monkey wrench in the works of our families and economy."

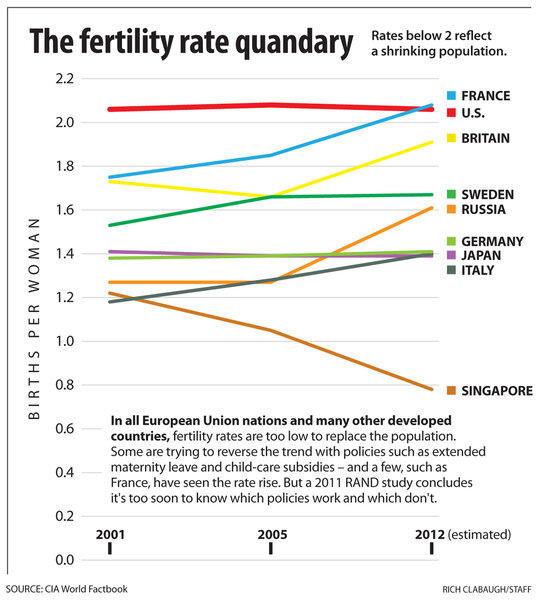

In some respects, the birthrate drop simply follows the century-long demographic glide path to smaller families, measured by fewer children per woman. Many nations in Western Europe, from Spain to Italy to Germany, are further along it, hitting a negative total fertility rate. America might have already hit that point, too, if not for higher immigration and the tendency of immigrant women to have more children than native-born women.

But the economic implications of a shrinking population are worrisome to many economists and political leaders. When the national fertility rate falls below the population replacement rate of 2.1 babies per woman – as it has in developed countries including Japan (1.4), Singapore (0.8), Norway (1.7), and Britain (1.9) – long-term plans for productivity and the social safety net become inviable.

For instance, America's Social Security program depends on having enough younger people in the workforce to cover benefits for retirees; a shortage of working-age people makes the program unsustainable at existing tax rates. Concern about low birthrates has led some nations to give their citizens financial incentives to have more children. Singapore, for one, now has a "Parenthood Package" that includes paternity leave, subsidies for fertility treatments, and special savings accounts for each child.

Of course, many factors are at work when it comes to a lower birthrate: delayed marriage, the advent of contraception, education and career options for women, economic stability, and so forth. It's not yet clear how much of a deterrent exorbitant and widespread student debt poses to family formation, because the phenomenon is relatively new.

"There are not a lot of hard numbers yet," says Tamika Butler, director of the California office of the Young Invincibles, a youth advocacy group that has focused on the student debt issue since 2009, conducting studies and making policy recommendations to Washington. A 2012 Rutgers University study, "Chasing the American Dream: Recent College Graduates and the Great Recession," shows that 4 in 10 graduates from a four-year college program said debt has delayed major decisions such as buying a house or starting a family. And there is plenty of anecdotal evidence that student debt is delaying childbearing.

'We would like to think about children, but ...'

Cassandra Coey graduated from The Ohio State University in 2010 with a degree in sociology. Between private and government loans, she owes at least $85,000. Her field is political consulting, but the lingering effects of the Great Recession have complicated her search for the ideal job. With student loan payments to make, she has taken whatever work is available, from fundraising for an environmental campaign to, more recently, a return to her college job in the food service industry. "I'm not even making $10 an hour," says Ms. Coey from her cellphone, coming off a shift at 10 p.m.

She and her boyfriend of three years have talked about marriage, "but he's really worried about what my debt would do to us," Coey says. "We would like to think about children, but how do children fit into that when you have to pay almost a thousand dollars a month just for the student loans?"

Hu, a recent graduate of Georgetown Law, treasures the idea of having a family, but she and her husband of five years opted to wait until she was out of school.

"Times were not bad back in 2007, but we thought it would not be a good idea for me to be pregnant during law school," she says. "Now, I look back at that decision and think maybe it would have been a better idea because at least when you are in school you don't have loan payments to worry about.... We ought to have two or three kids by now."

Buying a home and settling down, Hu says, are part of an "illusory" dream from the previous generation. How the couple would even begin to pay for their own children's college education is something she can't even think about.

Her situation, Hu adds, is "not unique at all. I am only one of many."

Indeed, during the recession, many freshly minted college graduates, unable to find jobs, instead enrolled in graduate school, acquiring even more student debt. Some individuals owe as much as $250,000.

"This is new," says Carl Van Horn, coauthor of the Rutgers study and director of the university's Heldrich Center for Workforce Development. "This is a very serious level of obligation, and it is affecting all the choices these graduates make."

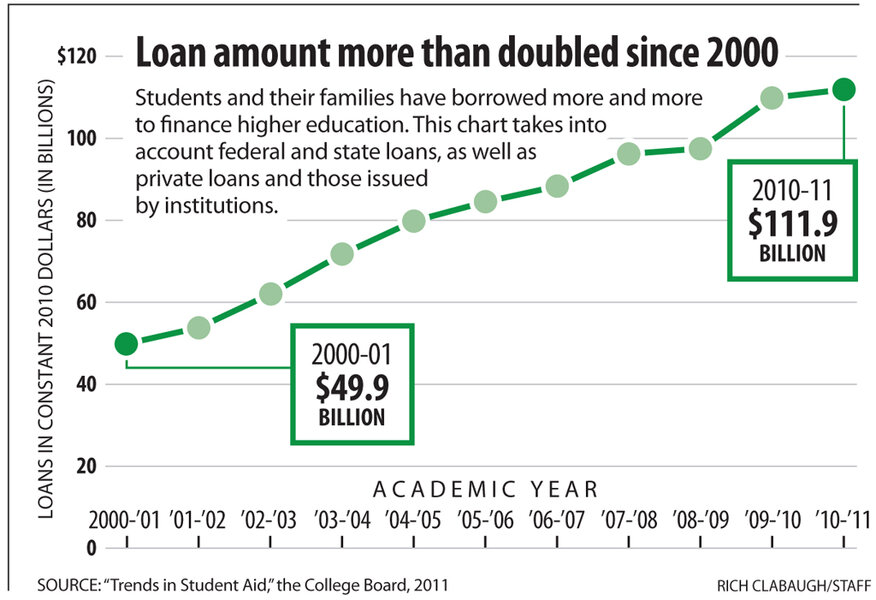

Collectively, the college loan bill in America comes to at least $1 trillion, the largest consumer debt sector outside of home mortgages, reports the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. This indebtedness, moreover, is concentrated among people younger than 40 – and it is accelerating much faster than the rate of inflation. The average college loan debt per student is nearing $27,000 – triple the average in 1992 – as a result of the soaring cost of college.

Hu and Coey both acknowledge that they were not very savvy about finances when they took out student loans. Inexperience and naiveté about financial products are nearly a universal problem among college students, many of whom have never even had a credit card, says Ms. Butler of the Young Invincibles. Moreover, student loans are the only form of consumer debt that cannot be discharged in bankruptcy.

Members of the group traveled the country during the past year to gather information about the student loan burden.

"What we found anecdotally," Butler says, "was one boyfriend or girlfriend after another saying they wanted to buy a house or start families, but they really wanted to pay off their student debt first."

Factors driving birthrate down

This new burden on decisionmaking stemming from student loan debt comes on top of other trends – some long-term, some short-term – that also work against childbearing. For one, more than 1 in 5 young adults ages 18 to 34 have delayed having a child because of the economic slowdown, approximately the same proportion that postponed marriage, a 2012 Pew survey found.

For another, the share of young adults ages 18 to 29 who are married fell from 59 percent in 1960 to 20 percent by 2010. The age at which men and women marry has also been creeping up, reaching an all-time high of 26.5 for women and 28.7 for men, according to Pew Research.

Big changes in the dynamics between men and women are also affecting marriage and childbearing, says psychologist and marriage counselor Wendy Walsh, author of the forthcoming book "The 30-Day Love Detox." For the first time in America's history, women outnumber men in higher education. As women gain more education and financial independence, they tend to marry less and later – and have fewer children, she notes.

Shifting sexual mores and the increased prevalence of cohabitation have only accelerated this trend, she adds. "More and more couples are [having children] without marrying at all," says Ms. Walsh, noting the attention lavished on celebrities who do likewise.

And the notion that immigration will stave off negative population growth in the United States is not as surefire as it used to be. The recent Pew study on the US birthrate noted that the drop was "led by a plunge in births to immigrant women." While the birthrate for US-born women fell 6 percent from 2007 to 2010, the rate for foreign-born women dropped by 14 percent during that time. These reductions may not turn around soon, as economies south of the border strengthen and fewer women there come to the US, says Mr. Christopher of IHS Global Insight.

Then there are the hard financial lessons of the recent recession, which baby-boomer parents are intent on driving home to their 20- and 30-something offspring.

"You have a Millennial generation [born after 1980] whose parents have just lived through the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression, and now we're telling them there are consequences to every financial decision, so be careful who you marry, why you marry, and when you have children," says Jim McGinnis, a divorce attorney and partner at Warner, Bates, McGough & McGinnis in Atlanta.

His own sons, ages 22 and 24, for example, couldn't be further from thoughts of marrying, buying a home, or having children, Mr. McGinnis says. The 24-year-old was just laid off from an internship. "They all went off to college thinking there would be plenty of people waiting to hire them when they got out," McGinnis says. "The big shock is that it just isn't so."

If the US birthrate does not pick up as the economy improves, the consequences could eventually be severe and far-reaching, warns Cheryl Carleton, a demographics expert and an assistant economics professor at Villanova University School of Business in Philadelphia.

For an economy to grow, it needs workers – and young workers are generally the most flexible and adaptable, she says.

Moreover, fewer children now means fewer children in the future, Dr. Carleton adds, noting the peril of a downward spiral toward negative population growth.

"Fewer younger people to care for an aging population puts more pressure on government to fund the care," she adds via e-mail. And, perhaps most important, a larger younger population provides more funding, through payroll taxes, to pay for Social Security for the older population.

First steps to lighten the load

Government efforts to ease the debt squeeze for young people have already begun. Congress voted over the summer to prevent the interest rate from doubling on some new federal student loans. And Washington has changed the repayment terms on certain loans, allowing forgiveness of a loan balance after 20 years of payments (if all terms are met) rather than after 25 years. Some loan repayments can also now be indexed to no more than 10 percent of the borrower's annual income.

Such changes, though, do not do much to help millions like Coey and Hu, who either have private lender loans that do not qualify for such breaks or don't have jobs that qualify them for a shortened time of loan repayment.

The long-term picture points to an irreversible trend in fertility rates across the globe, says Mark Rank, a social work professor at Washington University in St. Louis. "Back in 1800 it was around eight or nine [births] per woman, and now it's not even two," he says.

"But now it's time to invest in our people," relieving young people of outsized debts before they have even begun their working lives, he says. There's a precedent for such a step: the GI Bill after World War II that "helped with housing and education, and it made an enormous difference," Dr. Rank says.

In the past, he adds, noting the postwar spike in the US birthrate, "it paid off many times in terms of productivity."