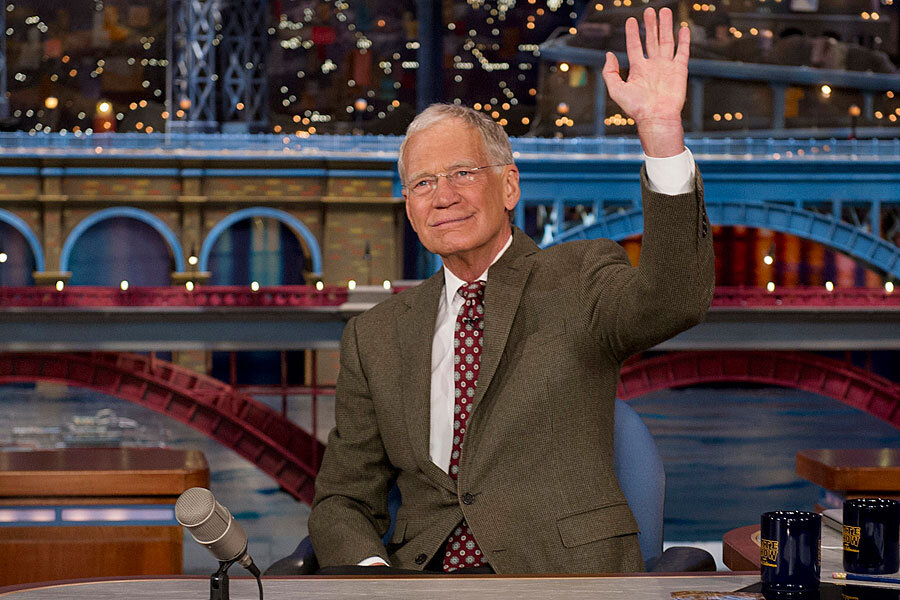

Late night's Letterman to retire: Did Gen X's oracle ever succeed at CBS?

Loading...

| New York

David Letterman may be a baby boomer, but he was an early patron saint for the Generation Xers who came of age in the 1980s, when television became their all-encompassing cultural medium, its commercials and marketing defining their lives.

Letterman, whose 32 years at the helm of a late-night talk show makes him the longest-running host in the history of the genre, announced he will retire from CBS’s “Late Show With David Letterman” in 2015, when his current contract expires.

But it was during his 11-year run on NBC’s “Late Night with David Letterman,” which ended in 1993 after a decade following the iconic “The Tonight Show,” that the grinning, gap-toothed comedian gave an early voice to the age of irony, revolutionizing a genre that had been defined by the bemused wise-cracking of more-staid hosts such as Steve Allen and Johnny Carson.

Indeed, when "Late Night" ended and Letterman moved to CBS to compete with longtime rival Jay Leno – who filled Carson’s chair at "The Tonight Show," a position Letterman craved – his act was never the same. "Late Show" never resonated with this one-hour-earlier audience the way that "Late Night" did with the younger generation who watched him in the '80s, and Leno beat him in the ratings for two decades.

But some 25 years ago at NBC, Letterman changed television, becoming the jokester who made fun of telling jokes, the TV personality who made fun of TV personalities, and the corporate shill who, in effect, made fun of corporate shilling.

He brought on the head of industrial sales for Velcro and, donning a full-body Velcro suit, trampolined onto a fuzzy wall – and stuck. He took the “plop plop fizz fizz” jingle of Alka-Seltzer and again, donning a suit covered with 3,400 of the white antacid tablets, plopped into a large glass aquarium of water and fizzed. And when General Electric took control of NBC in 1986, he tried to bring a congratulatory fruit basket to his new corporate parents.

“It was the early version of being ‘meta,’ " says Richard Laermer, a culture critic and author who heads RLM Public Relations in Manhattan. “It was anti-television on television, which was why people watched it.” (The term “meta” refers to creative works that are slyly self-conscious about the conventions of their genres.)

“He also made the joke about the celebrity for coming on his show, those doing the whole celebrity-movie-plug deal,” Mr. Laermer continues. “But he also gave them the opportunity to do it, and participated in the game. In a sense, it was like, here’s a pie in your face, but I’ll play along with the game anyway. And I think audience members really got into that. What’s he going to do to Farrah Fawcett tonight?”

Letterman created the NBC show in 1981 with his mentor and long-time idol, Johnny Carson, whose Carson Productions teamed with Letterman’s Space Age Meats Productions. Their idea was to target younger men, especially, because back then there wasn't much late-night programming catering to them.

“Letterman was a rare voice of authenticity cutting through the clutter of Reagan-era marketing and propaganda,” e-mails Aram Sinnreich, a media professor at Rutgers University School of Communication and Information in New Brunswick, N.J. “To those of us raised in the late Cold War, his flights of televised absurdity were sweet enough to make us smile, but just sharp enough to puncture the layer of phoniness and hype that blanketed nearly every broadcast on every medium.”

Professor Sinnreich recalls staying up late to watch Letterman in the mid-'80s, and then going to school the next day and acting out some of Dave's bits with his friends. Many others recorded the show on those new things called VCRs and watched it in the morning before heading out to school.

“Watching him felt like being in on an inside joke,” says Sinnreich. “Like he was getting away with something. Deconstructing network BS.”

Compared with those who experienced the earnest cultural revolutions of the 1960s, and even the more bacchanalian aggressiveness of the 1970s, the Gen Xers of the 1980s spent a lot of time talking and laughing about realities mediated through TV – from Saturday morning cartoons to “after school specials” to McDonald’s jingles sung as a hearty chorus in school cafeterias.

Letterman joked about the all-pervasive power of TV among youths in a 1983 sketch “They Took My Show Away” – a parody of the after-school genre. In the sketch, Dave explains to a little boy that his favorite show, “Voyagers,” had been canceled. The boy is inconsolable, and says, “I don’t think I’ll ever watch TV again!” Letterman says, “Jimmy, don't ever say that. Not even as a joke," going on to extol the new fall lineup for NBC.

put video here

The faux end credits read: “‘They Took My Show Away’ was made possible through a generous grant from the President’s Council For Longer Television Hours For Children.”

For many, Letterman’s comedy could both embrace the shared history of a generation reared on television, and at the same time undercut it ironically as being absurd and meaningless. Like most irony, it was a mask for a certain despair.

“Irony has been around for centuries ... but Generation X has commandeered it and speaks it as their native tongue,” wrote media scholar Mark Miller, author of “Boxed In: The Culture of TV,” in a 1997 essay about Letterman. “Why do Xers find David Letterman (a boomer, granted) so funny? Not because he tells great jokes, but because he mocks his own jokes. He stands outside himself and says, in effect, that the whole idea of his show is inane, and his entire twentysomething audience agrees – and laughs.”

While his run at the more conservative "Late Show" had its laughs, it never recaptured the innovating appeal of the earlier show.

“Unfortunately for Letterman, he stayed way past his prime and he'll be remembered for being cranky and perhaps for dissing [Sen. John] McCain more than anything,” says Laermer, the culture critic. “All the joy, ruckus, and fun from the [older] days are way behind him, and his inane jabs at Leno for 20 years have just made people roll their eyes.”