Muhammad Ali: How he became a global icon

He was fast of fist and foot — lip, too — a heavyweight champion who promised to shock the world and did. He floated. He stung. Mostly he thrilled, even after the punches had taken their toll and his voice barely rose above a whisper.

He was The Greatest.

Muhammad Ali died Friday at age 74, according to a statement from the family. He was hospitalized in the Phoenix area with respiratory problems earlier this week, and his children had flown in from around the country.

"Muhammad Ali shook up the world. And the world is better for it. We are all better for it," President Obama said. Obama likened Ali, to other civil rights leaders of his era, and said the boxer stood with Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela in fighting for what was right.

Obama said that after Ali's boxing career ended, he became an even more "powerful force for peace and reconciliation around the world."

"It's a sad day for life, man. I loved Muhammad Ali, he was my friend. Ali will never die," Don King, who promoted some of Ali's biggest fights, told The Associated Press early Saturday. "Like Martin Luther King his spirit will live on, he stood for the world."

A funeral will be held in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky. The city plans a memorial service Saturday.

Louisville Mayor Greg Fischer ordered flags lowered to half-staff to honor Ali.

"The values of hard work, conviction and compassion that Muhammad Ali developed while growing up in Louisville helped him become a global icon," Fischer said. "As a boxer, he became The Greatest, though his most lasting victories happened outside the ring."

With a wit as sharp as the punches he used to "whup" opponents, Ali dominated sports for two decades.

He won and defended the heavyweight championship in epic fights in exotic locations, spoke loudly on behalf of blacks, and famously refused to be drafted into the Army during the Vietnam War because of his Muslim beliefs.

Despite his debilitating illness (he was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease), he traveled the world to rapturous receptions even after his once-bellowing voice was quieted and he was left to communicate with a wink or a weak smile.

"He was the greatest fighter of all time but his boxing career is secondary to his contribution to the world," promoter Bob Arum told the AP early Saturday. "He's the most transforming figure of my time certainly."

Revered by millions worldwide and reviled by millions more, Ali cut quite a figure, 6-foot-3 and 210 pounds in his prime. "Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee," his cornermen exhorted, and he did just that in a way no heavyweight had ever fought before.

He fought in three different decades, finished with a record of 56-5 with 37 knockouts — 26 of those bouts promoted by Arum — and was the first man to win heavyweight titles three times.

He whipped the fearsome Sonny Liston twice, toppled the mighty George Foreman with the rope-a-dope in Zaire, and nearly fought to the death with Joe Frazier in the Philippines. Through it all, he was trailed by a colorful entourage who merely added to his growing legend.

"Rumble, young man, rumble," cornerman Bundini Brown would yell to him.

And rumble Ali did. He fought anyone who meant anything and made millions of dollars with his lightning-quick jab. His fights were so memorable that they had names — "Rumble in the Jungle" and "Thrilla in Manila."

But it was as much his antics — and his mouth — outside the ring that transformed the man born Cassius Clay into a household name as Muhammad Ali.

"I am the greatest," Ali thundered again and again.

Few would disagree.

Ali spurned white America when he joined the Black Muslims and changed his name. He defied the draft at the height of the Vietnam war — "I ain't got no quarrel with them Viet Cong" — and lost 3 1/2 years from the prime of his career. He entertained world leaders, once telling Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos: "I saw your wife. You're not as dumb as you look."

He later embarked on a second career as a missionary for Islam.

"Boxing was my field mission, the first part of my life," he said in 1990, adding with typical braggadocio, "I will be the greatest evangelist ever."

Ali couldn't fulfill that goal because Parkinson's robbed him of his speech. "People naturally are going to be sad to see the effects of his disease," Hana, one of his daughters, said, when he turned 65. "But if they could really see him in the calm of his everyday life, they would not be sorry for him. He's at complete peace, and he's here learning a greater lesson."

The quiet of Ali's later life was in contrast to the roar of a career that had breathtaking highs along with terrible lows. He exploded on the public scene with a series of nationally televised fights that gave the public an exciting new champion, and he entertained millions as he sparred verbally with the likes of bombastic sportscaster Howard Cosell.

Ali once calculated he had taken 29,000 punches to the head and made $57 million in his pro career. That didn't stop him from traveling tirelessly to promote Islam, meet with world leaders and champion legislation dubbed the Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act. While slowed in recent years, he still managed to make numerous appearances, including a trip to the 2012 London Olympics.

Despised by some for his outspoken beliefs and refusal to serve in the U.S. Army in the 1960s, an aging Ali became a poignant figure whose mere presence at a sporting event would draw long standing ovations.

With his hands trembling, he lit the Olympic torch for the 1996 Atlanta Games in a performance as riveting as some of his fights.

A few years after that, he sat mute in a committee room in Washington, his mere presence enough to convince lawmakers to pass the boxing reform bill that bore his name.

Members of his inner circle weren't surprised. They had long known Ali as a humanitarian who once wouldn't think twice about getting in his car and driving hours to visit a terminally ill child. They saw him as a man who seemed to like everyone he met — even his archrival Frazier.

"I consider myself one of the luckiest guys in the world just to call him my friend," former business manager Gene Kilroy said. "If I was to die today and go to heaven it would be a step down. My heaven was being with Ali."

One of his biggest opponents would later become a big fan, too. On the eve of the 35th anniversary of their "Rumble in the Jungle," Foreman paid tribute to the man who so famously stopped him in the eighth round of their 1974 heavyweight title fight, the first ever held in Africa.

"I don't call him the best boxer of all time, but he's the greatest human being I ever met," Foreman said. "To this day he's the most exciting person I ever met in my life."

Born Cassius Marcellus Clay on Jan. 17, 1942, in Louisville, Kentucky, Ali began boxing at age 12 after his new bicycle was stolen and he vowed to policeman Joe Martin that he would "whup" the person who took it.

He was only 89 pounds at the time, but Martin began training him at his boxing gym, the beginning of a six-year amateur career that ended with the light heavyweight Olympic gold medal in 1960.

Ali had already encountered racism. On boxing trips, he and his amateur teammates would have to stay in the car while Martin bought them hamburgers. When he returned to Louisville with his gold medal, the Chamber of Commerce presented him a citation but said it didn't have time to co-sponsor a dinner.

In his autobiography, "The Greatest," Ali wrote that he tossed the medal into the Ohio River after a fight with a white motorcycle gang, which started when he and a friend were refused service at a Louisville restaurant.

The story may be apocryphal, and Ali later told friends he simply misplaced the medal. Regardless, he had made his point.

After he beat Liston to win the heavyweight title in 1964, Ali shocked the boxing world by announcing he was a member of the Black Muslims — the Nation of Islam — and was rejecting his "slave name."

As a Baptist youth he spent much of his time outside the ring reading the Bible. From now on, he would be known as Muhammad Ali and his book of choice would be the Koran.

Ali's affiliation with the Nation of Islam outraged and disturbed many white Americans, but it was his refusal to be inducted into the Army that angered them most.

That happened on April 28, 1967, a month after he knocked out Zora Folley in the seventh round at Madison Square Garden in New York for his eighth title defense.

He was convicted of draft evasion, stripped of his title and banned from boxing.

Ali appealed the conviction on grounds he was a Muslim minister. He married 17-year-old Belinda Boyd, the second of his four wives, a month after his conviction, and had four children with her. He had two more with his third wife, Veronica Porsche, and he and his fourth wife, Lonnie Williams, adopted a son.

During his banishment, Ali spoke at colleges and briefly appeared in a Broadway musical called "Big Time Buck White." Still facing a prison term, he was allowed to resume boxing three years later, and he came back to stop Jerry Quarry in three rounds on Oct. 26, 1970, in Atlanta despite efforts by Georgia Gov. Lester Maddox to block the bout.

He was still facing a possible prison sentence when he fought Frazier for the first time on March 8, 1971, in what was labeled "The Fight of the Century."

A few months later the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the conviction on an 8-0 vote.

"I've done my celebrating already," Ali said after being informed of the decision. "I said a prayer to Allah."

Many in boxing believe Ali was never the same fighter after his lengthy layoff, even though he won the heavyweight championship two more times and fought for another decade.

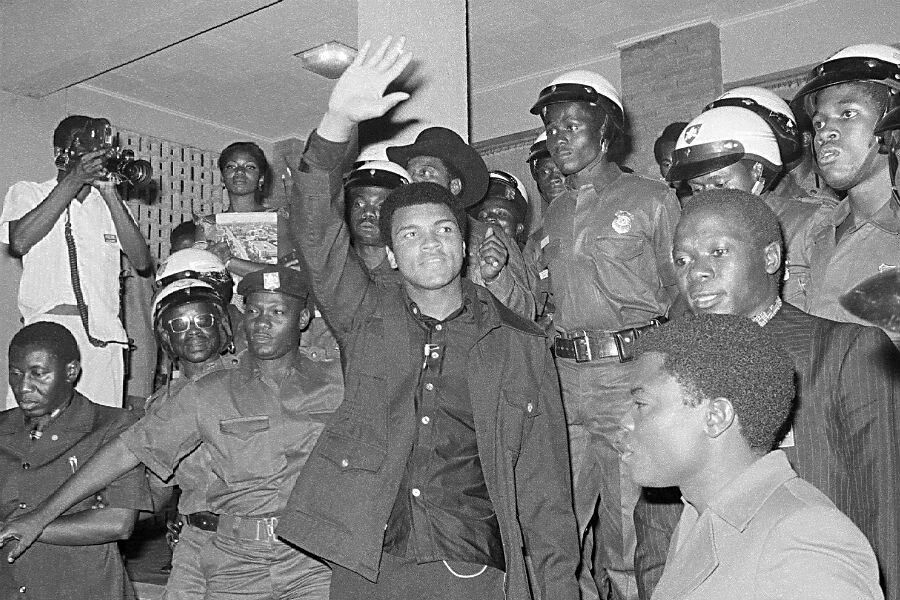

Perhaps his most memorable fight was the "Rumble in the Jungle," when he upset a brooding Foreman to become heavyweight champion once again at age 32.

Many worried that Ali could be seriously hurt by the powerful Foreman, who had knocked Frazier down six times in a second round TKO.

But while his peak fighting days may have been over, he was still in fine form verbally. He promoted the fight relentlessly, as only he could.

"You think the world was shocked when Nixon resigned," he said. "Wait till I whup George Foreman's behind."

Ali won over a country before he won the fight, mingling with people as he trained and displaying the kind of playful charm the rest of the world had already seen. On the plane into the former Congo he asked what the citizens of Zaire disliked most. He was told it was Belgians because they had once colonized the country.

"George Foreman is a Belgian," Ali cried out to the huge crowd that greeted him at the airport. By the time the fight finally went off in the early morning hours of Oct. 30, 1974, Zaire was his.

"Ali booma-ya (Ali kill him)," many of the 60,000 fans screamed as the fight began in Kinshasa.

Ali pulled out a huge upset to win the heavyweight title for a second time, allowing Foreman to punch himself out. He used what he would later call the "rope-a-dope" strategy — something even trainer Angelo Dundee knew nothing about.

Finally, he knocked out an exhausted Foreman in the eighth round, touching off wild celebrations among his African fans.

"I told you I was the greatest," Ali said.

That might have been argued by followers of Joe Louis or Rocky Marciano or Sugar Ray Robinson, but there was no doubt that Ali was just what boxing needed in the early 1960s.

He spouted poetry and brash predictions. After the sullen and frightening Liston, he was a fresh and entertaining face in a sport that struggled for respectability.

At the weigh-in before his Feb. 25, 1964, fight with Liston, Ali carried on so much that some observers thought he was scared stiff and suggested the fight in Miami Beach be called off.

"The crowd did not dream when they lay down their money that they would see a total eclipse of the Sonny," Ali said.

Ali went on to punch Liston's face lumpy and became champion for the first time when Liston quit on his stool after the sixth round.

"Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee," became Ali's rallying cry.

His talent for talking earned him the nickname "The Louisville Lip," but he had a new name of his own in mind: Muhammad Ali.

"I don't have to be what you want me to be," he told reporters the morning after beating Liston. "I'm free to be who I want."

Frazier refused to call Ali by his new name, insisting he was still Cassius Clay. So did Ernie Terrell in their Feb. 6, 1967, fight, a mistake he would come to regret through 15 long rounds.

"What's my name?" Ali demanded as he repeatedly punched Terrell in the face. "What's my name?"

By the time Ali was able to return to the ring following his forced layoff, he was bigger than ever. Soon he was in the ring for his first of three epic fights against Frazier, with each fighter guaranteed $2.5 million.

Before the fight, Ali called Frazier an "Uncle Tom" and said he was "too ugly to be the champ." His gamesmanship could have a cruel edge, especially when it was directed toward Frazier.

In the first fight, though, Frazier had the upper hand. He relentlessly wore Ali down, flooring him with a crushing left hook in the 15th round and winning a decision.

It was the first defeat for Ali, but the boxing world had not seen the last of him and Frazier in the ring. Ali won a second fight, and then came the "Thrilla in Manila" on Oct. 1, 1975, in the Philippines, a brutal bout that Ali said afterward was "the closest thing to dying" he had experienced.

Ali won that third fight but took a terrific beating from the relentless Frazier before trainer Eddie Futch kept Frazier from answering the bell for the 15th round.

"They told me Joe Frazier was through," Ali told Frazier at one point during the fight.

"They lied," Frazier said, before hitting Ali with a left hook.

The fight — which most in boxing agree was Ali's last great performance — was part of a 16-month period on the mid-1970s when Ali took his show on the road, fighting Foreman in Zaire, Frazier in the Philippines, Joe Bugner in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, and Jean Pierre Coopman in Puerto Rico.

The world got a taste of Ali in splendid form with both his fists and his mouth.

In Malaysia, a member of the commission in charge of the gloves the fighters would wear told Ali they would be held in a prison for safekeeping before the fight.

"My gloves are going to jail," shouted a wide-eyed Ali. "They ain't done nothing — yet!"

Ali would go on to lose the title to Leon Spinks, then come back to win it a third time on Sept. 15, 1978, when he scored a decision over Spinks in a rematch before 70,000 people at the Superdome in New Orleans.

Ali retired, only to come back and try to win the title for a fourth time against Larry Holmes on Oct. 2, 1980, at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. Ali grew a mustache, pronounced himself "Dark Gable" and got down to a svelte 217 1/2 pounds to beat Father Time. But Holmes, his former sparring partner, mercifully toyed with him until Dundee refused to let Ali answer the bell for the 11th round.

"He was like a little baby after the first round," Holmes said. "I was throwing punches and missing just for the hell of it. I kept saying, 'Ali, why are you taking this?'

"He said, 'Shut up and fight, I'm going to knock you out.'"

When the fight was over, Holmes and his wife went upstairs to pay their respects to Ali. In a darkened room, Holmes told Ali that he loved him.

"Then why did you whip my ass like that?" Ali replied.

A few years later, Ali said he would not have fought Holmes if he didn't think he could have won.

"If I had known Holmes was going to whip me and damage my brain, I would not have fought him," Ali said. "But losing to Holmes and being sick are not important in God's world."

It was that world that Ali retreated to, fighting just once more, losing a 10-round decision to Trevor Berbick in the Bahamas.

With his fourth wife, Lonnie, at his side, Ali traveled the world for Islam and other causes. In 1990, he went to Iraq on his own initiative to meet with Saddam Hussein and returned to the United States with 15 Americans who had been held hostage.

One of the hostages recounted meeting Ali in Thomas Hauser's 1990 biography "Muhammad Ali — His Life and Times."

"I've always known that Muhammad Ali was a super sportsman; but during those hours that we were together, inside that enormous body I saw an angel," hostage Harry Brill-Edwards said.

For his part, Ali didn't complain about the price he had paid in the ring.

"What I suffered physically was worth what I've accomplished in life," he said in 1984. "A man who is not courageous enough to take risks will never accomplish anything in life."