Muhammad Ali, the showman

The image of heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali always liked best was the one that appeared regularly in his bedroom mirror.

Sportscaster Howard Cosell always claimed that Ali was the greatest heavyweight champion of all time. But that’s not just Cosell’s opinion; it was also Ali’s, who was filled with pomp, whatever the circumstance.

When Ali died Friday in Phoenix, the news of his passing was as big in Saudi Arabia as it was in New York City.

He was so skilled at protecting his face and body that most of his opponent’s punches didn’t have enough steam in them to press a pair of pants. The fight crowd loved it.

Ali, who began his career as Cassius Clay, often traveled with an entourage of hangers-on who constantly fed him compliments while milking him for huge amounts of money.

His biggest challenges in the ring came against skilled veterans like Joe Frazier, Ken Norton, Larry Holmes, and George Foreman.

Ali won most of the time, but somebody should have started to count the repeated blows to the head that would eventually slur his speech, affect his coordination, and turn what was once perfect balance in the ring into physical trauma.

As boxing’s Mouth That Roared, he was the sport’s ultimate showman.

When Ali was asked to speak at Harvard University’s Faculty Club in 1975, he charmed a jammed press conference with oratory skills not unlike those of veteran politician Tip O’Neill.

Asked why he had pursued a boxing career, Ali explained: “It’s not the action that makes a thing right or wrong, but the purpose. My purpose is to help people and I can do it through boxing.”

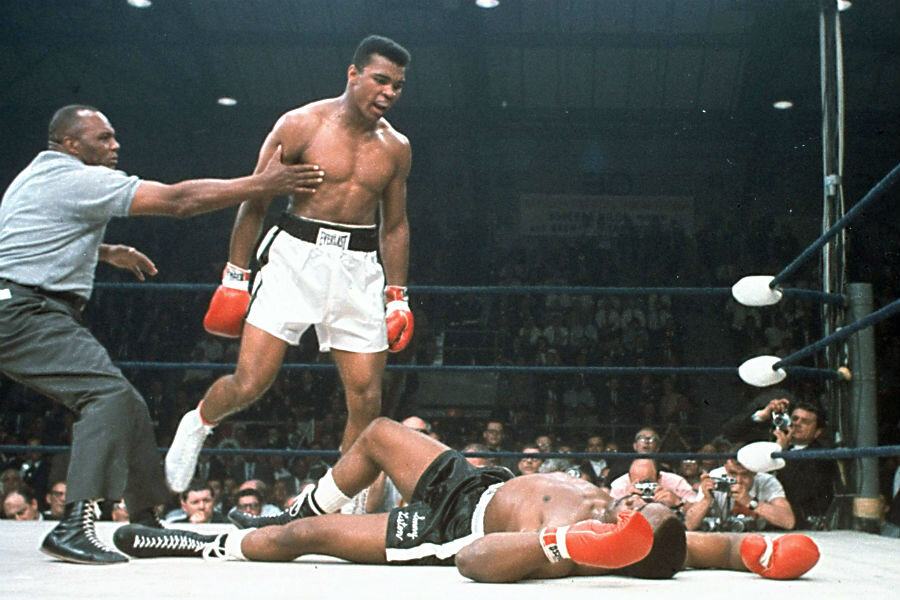

A couple of times I bought a theater ticket to watch Ali fight on the big screen, including his first encounter with Sonny Liston.

Once, after I had returned from covering a Boston Celtics road game against the Cincinnati Royals, he entered my hotel with his usual followers and turned the lobby into a circus.

The only time I really got close to Ali was after he headlined a press conference in 1979 at the Fabulous Forum in Los Angeles and he talked about how glad he was that he had finally put his boxing gloves in mothballs. It might have been one of the few serious moments in his life and he was willing to share it with the public.

“I’m happy to be getting out of boxing because the temptations, the fights, the pressure from the press have been too much,” he explained. “It isn’t easy to go out a winner. I’ve had so many close calls, taken so many gambles.

“In looking back, I don’t know how I got away with some of the things I did,” he continued. “Most people who paid to see me were hoping that I’d get beat But look at my face. Can you believe I’ve been fighting for 25 years? I’m still a pretty man.”

Presumably when Ali was talking about close calls, he was referring to opponents Sonny Banks, Henry Cooper, and Joe Frazier, all of whom unexpectedly decked him with left hands.

Ali went on to say that his crazy actions over the years at weigh-ins and press conferences are always planned ahead of time. They were designed by him to hype the gate and keep his name before the public.

“Early in my career as a fighter, I was in Las Vegas and there was this wrestler who called himself Gorgeous George,” Ali said. “I watched him bragging, saying he was pretty, how bad he was going to whup his opponent, and how, if there were even two empty seats in the arena that night, he wasn’t coming out of his dressing room.

“Anyway, Gorgeous George came into the ring carrying a mirror while two attractive young ladies held up his fancy robe so it wouldn’t touch the floor.

“While one of his handlers sprayed the other guy’s corner with a can of deodorant, most of the crowd was booing Gorgeous George. But they all paid to get in and deep down I could tell that George was laughing. So I decided to do the same thing, only I did it better.”

Questioned about when he decided to retire from boxing, Ali replied: “I decided to retire the minute I beat Leon Spinks and the announcer in the ring said, ‘Three-time heavyweight champion of the world.’ ”

Of course, even after his 1979 retirement event in L.A., he fought again. His actual retirement came two years later.

Ali said his best fight was the “Thrilla in Manila” against Joe Frazier; his most rewarding against Spinks; and his most devastating the first time he met Foreman, when George broke his jaw. However, it was the second Frazier fight that he believed began to cost him his health and the chance to continue a normal life.

Ali liked money and women and headlines and the good life.

Among the places where he landed championship punches and made the long rainbow laces of his shoes dance like a Benny Goodman cadenza were such far-away locales at Kuala Lumpur, Manila, Kinshasa, Munich, Frankfort, Jakarta, London, and Tokyo.

Phil Elderkin, who was a National Headliners’ Award in 1975 for Outstanding Commentary on Sports, is a former sports editor of the Monitor.