Did USA Gymnastics fail to protect young gymnasts from sex abuse?

Loading...

For years, USA Gymnastics, the national governing body for the sport of gymnastics in the United States, ignored sexual abuse allegations against numerous coaches, routinely dismissing them as “hearsay unless they came directly from a victim or victim’s parents” because the organization worried false claims would ruin a coach’s reputation, according to an investigation by the Indianapolis Star.

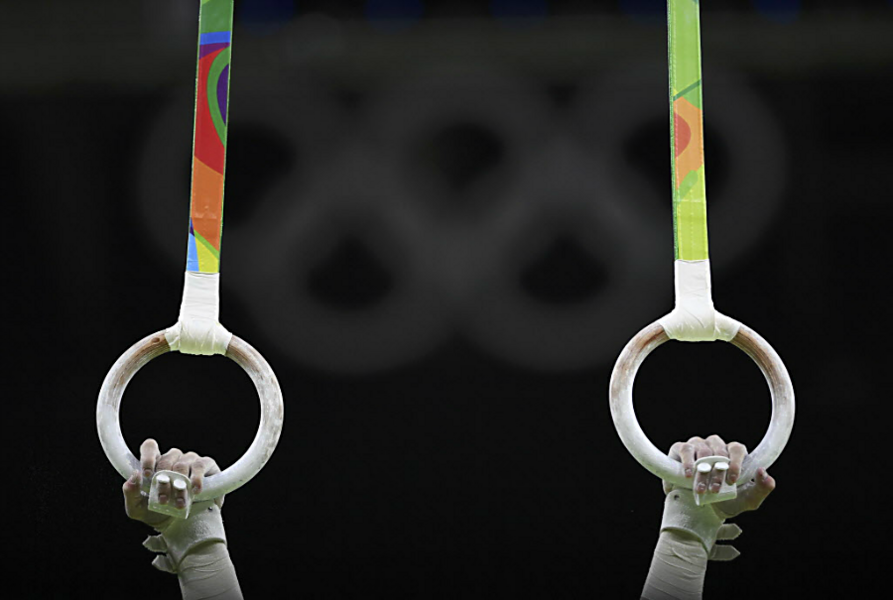

Sexual abuse in the sport isn’t new. The IndyStar investigation, however, published on the eve of the 2016 Olympics set to open on Friday, said the sport’s governing body systematically protected coaches over the welfare of young athletes. The investigation also lays bare an attitude that has reared its head in other sports, including the football program at Penn State University.

"Some in the gymnastics community told IndyStar they question whether USA Gymnastics is too preoccupied with producing Olympic champions, winning sponsorships and growing the sport – or too conflicted about protecting its image – to ensure the safety of tens of thousands of children in gymnastics," writes the newspaper's Marisa Kwiatkowski, Mark Alesia, and Tim Evans.

One former member of the US national team, Molly Shawen-Kollmann, said the organization "is thinking about the Olympics, then the World Championships. It’s go, go, go."

"That’s how they have to be,” she said.

IndyStar said it found a policy and culture in USA Gymnastics that created an atmosphere in which officials failed to report sexual abuse allegations unless they came from either victims or their families. In the case of William McCabe, a former coach convicted of sexual exploitation in Florida, the organization acknowledged in court records that it rarely brought forward allegations of child abuse to authorities unless it was requested to do so. When questioned under oath, Steve Penny, the organization’s president, and his predecessor, Robert Colarossi, said "unsubstantiated allegations" from anyone besides victims or their families could result in a “witch hunt.”

“People might have all kinds of reasons for saying things,” said Mr. Penny.

Instead, the organization compiled complaint dossiers on 54 coaches that it filed away in a drawer in its executive office in Indianapolis, according to court records. IndyStar, as part of the USA Today network, filed a motion to make the files public. The judge in that case has not yet ruled.

Even without those files, IndyStar uncovered four cases of coaches who were accused of continuing to abuse athletes after the organization received complaints against them. This includes Mr. McCabe and Marvin Sharp, who mentored two Olympic athletes, one to a silver medal. Mr. Sharp was convicted of possessing a trove of child pornography, and giving his athletes private sports massages. Sharp died of an apparent suicide inside his jail cell in September.

In his response to the IndyStar’s report, Penny, speaking on behalf of USA Gymnastics, said he initiated the report of Sharp to law enforcement.

"USA Gymnastics seeks first-hand knowledge whenever allegations of abuse arise as the most reliable source to take action and as outlined in its bylaws and policies," said Penny, in a statement. "The organization has continually reviewed its best practices on how it addresses these issues and has been among the first to initiate new policies and procedures including publishing a list of banned coaches and instituting national background checks."

"We find it appalling that anyone would exploit a young athlete or child in this manner, and recognize the effect this behavior can have on a person's life," he added.

Jennifer Sey, a former national champion gymnast and author of her memoir, "Chalked Up," offered an insider's perspective into why abuse allegations might be overlooked. In an article that appeared in Salon in November 2011, she recalled when she suspected one of her teenage teammates was being abused by Don Peters, the coach of their team at the 1986 Goodwill Games. The teammate, Doe Yamashiro, and another gymnast finally told the Orange County Register about the abuse in 2011. USA Gymnastics then permanently banned Mr. Peters that year, and his place in the organization's Hall of Fame was revoked.

In the microcosmic world of hyper-competitive athletics, a high-performance culture where winning trumps all, obvious moral choices become blurred. The sport, the team, a berth on the squad, a medal on the stand – that becomes the priority. The parents, coaches and teams put everything else aside in honor of the win.

Morality viewed in the funhouse mirror of elite athletics is grotesquely distorted. And the distortion becomes invisible after a time. A parent or coach might say: What if the reports aren’t true? It would be unthinkable to ruin this great man’s reputation. Oh, and by the way, he might not let my daughter/gymnast compete in the next big meet if I implicate him in such ugliness. This all-powerful man will strike back and my daughter/athlete will suffer. We’ve worked too hard. Let’s let it slide.

Parents and others have been accused of reporting false claims against coaches in other sports as well. One example is in Minnesota, where a high school hockey coach resigned amid allegations by one parent that he psychologically abused and physically assaulted players. Jeff Pauletti, the coach, sued the parent in March 2015. The state legislature responded to the case by passing a law that prevented coaches from being fired just because of parental complaints. Abuse scandals in other sports have shown that not reporting allegations can cost coaches their careers and reputations.

Perhaps the highest profile case is that of Joe Paterno, the former coach of Penn State's Nittany Lions college football team. Jerry Sandusky, a longtime assistant coach under Mr. Paterno, was convicted in 2012 of being a serial child molester. Paterno and others at the university were said to be aware of the allegations, but never reported them to police.

Ms. Sey, the gymnast, said these stories of abuse underscore the need for better guidelines and attitudes toward addressing allegations.

"We all must insist that coaches are teachers of children first, and champion builders a far, far distant second," she wrote.