Sober high: How 'recovery schools' help addicted students

| BROCKTON, MASS.

Skinny and brimming with nervous energy, Matt Langley grew up with an outlook that was anything but upbeat. “I guess I was never comfortable in my own skin,” he says. “Everything that came out of my mouth, I would second-guess.”

Drugs relieved him of that burden. He started with marijuana, which he says a friend’s mother introduced him to at age 13. Over the next six years, more powerful substances followed: Ecstasy, acid. Then, he says, “A friend of mine asked if I’d like to try Xanax,” a prescription drug used to treat anxiety disorders that, when misused, can be highly addictive. That was in January 2016.

For the next six months, he took Xanax every day. “I’ve never experienced such euphoria,” he says. He crash-landed at a state-funded detox center, where he stayed for a month. When he came out, he says, “I knew I couldn’t stay sober by myself.”

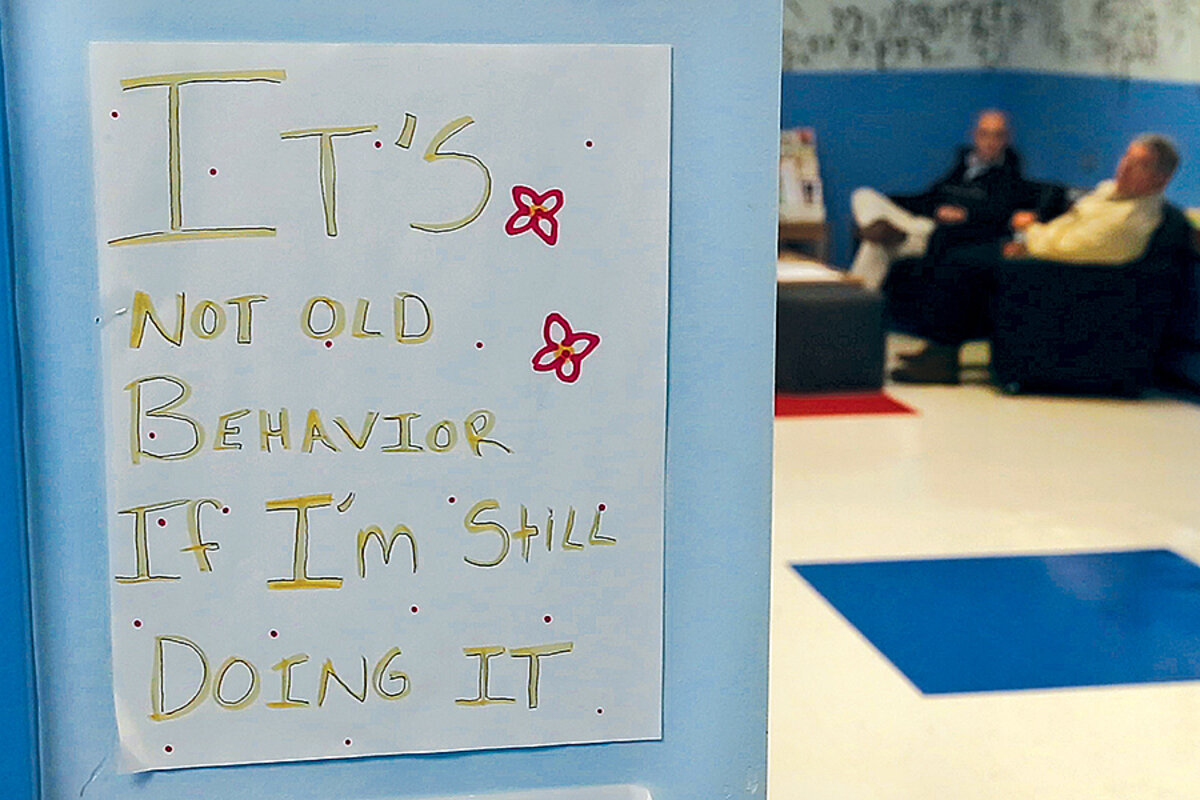

Seeking help, he enrolled at Independence Academy in Brockton, Mass., where posters and signs covering the walls bear such messages as “My worst day sober is better than my best day high.”

Mr. Langley and the school’s 21 other students – many of whom, like Langley, abused drugs for years – face a daily struggle to stay clean.

Independence Academy is one of 33 so-called recovery schools in the United States, public high schools that serve students whose lives and educations have been derailed by drug abuse.

While national surveys indicate that adolescent drug use has fallen in recent years, some 1.3 million 12- to 17-year-olds still met the criteria for a substance use disorder in 2014. That includes 679,000 young people who struggled with alcohol problems and another 168,000 who misused pain relievers.

Providing early treatment for teens is considered critical. Studies find that 9 in 10 adults with addiction problems began their chemical dependency before age 18. In Massachusetts, unintentional overdoses of opioids alone claimed 1,465 lives statewide in 2016 – up from 613 in 2011. Among the fatalities were 114 individuals under age 25.

Before the advent of recovery schools, parents had few options for dealing with a son or daughter who had a drug problem. They could seek private treatment, but gaining access to services isn’t easy. In many states, the wait to get an evaluation from an adolescent psychiatrist can take three to six months.

Then, when the treatment ends, the teens usually go back to their normal schools, where the temptation to start abusing drugs again can be strong. At recovery schools, they get reinforcement from students facing the same problems.

In Brockton – a once-prosperous town called “Shoe City” until the last of its footwear factories closed in 2009 – drugs are plentiful. A tainted batch of heroin hit the streets in January 2016, causing 40 overdoses in just two days.

Most teenagers at Independence Academy struggle with alcohol and marijuana abuse. To be admitted, they must pledge to abstain from using and submit to random drug testing. Students are referred by residential drug-treatment programs, school districts, or parents desperate for help.

Once they’re in, the hope is that a culture of “positive peer pressure” will help teens stay sober. They also receive intensive counseling to find ways to stave off addictive urges and to address whatever got them using in the first place. Schools like Independence Academy have been called “sober high schools,” but while abstinence is the goal, the reality is more complex.

Like Langley, many students here come to Independence Academy after a stay in detox. Going back to their old school could hinder their progress.

“My friends are all proud of me,” Langley says, “but they’re all addicts and I can’t be around them or I’ll start using.”

Independence Academy opened its doors in 2012, and is now one of five such schools in the state funded and overseen by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

Brockton Mayor Bill Carpenter led the campaign to open the school here. He has direct experience with teenagers and addiction. “Twelve years ago, my son became addicted to heroin while he was a student at Brockton High School,” he says.

As a parent, Mr. Carpenter says he tried to do all the right things for his son. “We did 90-day residential programs followed by intensive outpatient [treatment], and then we’d get him back to school because I thought that’s what you’re supposed to do – get your 16-year-old back in school,” Carpenter says. “What I should have understood at the time – and didn’t – was that we were throwing him back into the fire.”

During the period right after treatment, when teenagers return to school and reconnect with friends, the risk of relapse runs high. Schools like Independence Academy offer an alternative.

“Instead of going back to your old group of friends, who are going to encourage you to go back to drug use, you’re now in a completely different environment of support,” Carpenter says. “You have other kids like yourself that are fighting some of the same struggles.”

Langley started at Independence last July and likes the small size: With just 22 students, it’s among the smallest high schools in the state. “I’ve made new friends here,” he says. “Probably the first new friends that I’ve made in years.”

The vibe is different, too. Independence Academy’s entryway is piled high with skateboards, scooters, and bikes. Students are encouraged to use them whenever they feel like it. “If I’m getting stressed out in math class, I can just say to the teacher, ‘I need to go out,’ ” Langley says. “I’ll grab a bike and ride for a little while, come in again, and get right back to math.”

While the academic program here leads toward a regular Massachusetts high school diploma, the teaching is often tailored to address individual areas of weakness. Most classes meet in a large central room that feels part art studio, part living room. Murals and paintings decorate the walls, while couches and comfy armchairs invite students to relax. The students often work independently, on laptops, with headphones plugged in. It’s a tranquil space that reflects the school’s philosophy.

“It’s similar to the way you’d approach trauma,” says teacher Shawn Kain. “Kids who are stressed out, kids who are anxious, are not going to retain new information.”

Teachers here say they spend about half their time just getting students caught up. Amber, who is 17 and whose last name is being withheld to protect her identity because she is a minor, started using marijuana in fifth grade. A couple of years later she discovered Xanax.

“I’d wake up in the morning, pop a bar of Xanax, smoke a couple blunts,” she says. “I’d do Xanies before school and I’d be half asleep in class and no one would say anything to me.”

Drug use, suspensions, and expulsions have put many students here far behind academically. While Massachusetts high schools adhere to the relatively tough Common Core academic standards, the priority at Independence Academy is on meeting students where they are. “The standard is what’s appropriate,” Mr. Kain says. “If you give students an expectation that stresses them out and it’s overwhelming, then they shut down.”

It’s hard to know how Massachusetts recovery high schools perform academically. While regular public high schools report graduation rates and scores on standardized tests, the same data aren’t widely available for recovery schools, because many are so small they fall below the threshold for reporting.

What’s more, for many students the stay at a recovery high school is short. The schools often serve as “soft-landing” zones, allowing students to slowly transition back to their regular high schools. At Massachusetts’ five recovery high schools, the average stay is six to seven months.

Some indication of academic results, however, can be found in a 2011 study by Thomas Kochanek for the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Examining five years of data from two of the recovery schools in operation at that time, Dr. Kochanek found that 41 percent of students graduated, 41 percent transferred back to their home school or a GED program, and 13 percent transferred to a treatment facility or program or were incarcerated. The remaining 5 percent either were expelled or dropped out.

All recovery high schools face one potential problem – limited course offerings. “I don’t have AP classes, Russian literature, or robotics because we don’t have the critical numbers to staff those,” says Michael Durchslag, director at PEASE Academy (which stands for Peers Enjoying a Sober Education), a recovery high school in Minneapolis that currently enrolls 50 students.

Limited course offerings at PEASE cause some parents to hesitate to enroll their kids, fearing they will miss out. Mr. Durchslag seeks to reassure them. “I know that students who come here don’t give up a quality education,” he says. “I mean, I have a graduate who just finished up her third year of residency in medical school, so I don’t think it’s going to hold anyone back.”

At Independence Academy, Kain also isn’t terribly concerned about course offerings. While his school does have partnerships with other local high schools allowing students who are academically ready to take classes off-site, he believes that what most students need is more fundamental. “We are very good at customizing education and getting kids into a good school routine,” says Kain.

Most recovery high schools go to great lengths to prevent students from relapsing. At Independence, for example, a full-time clinical social worker, Karin Burke-Lewis, meets with each student two or three times a week for intensive recovery counseling. On the small conference table in her office, Ms. Burke-Lewis keeps a large red bucket plastered with a Boston Red Sox logo. Inside, it’s full of squishy, brightly colored stress balls. Students pop in all the time to dig through her collection, and Burke-Lewis, who’s good at getting them talking, has come to know them well.

“Many of these students come from really complex struggles – stress, abandonment, and abuse are common,” she says. “Before coming here, the way they’ve handled that was to pick up a substance.”

Working closely with each student, she designs a “relapse prevention plan” that involves helping students clarify and visualize their goals. “It could be graduating from high school, it could be sustaining employment, it could be ‘I want to not use for a month, consistently,’ ” Burke-Lewis says.

In addition to providing one-on-one help, Independence Academy seeks to create peer-to-peer support. Each Thursday afternoon students meet for a session of SMART Recovery, an abstinence-based curriculum that teaches them how to cope with urges and manage their thoughts and feelings.

On Fridays, the students gather with Burke-Lewis to make plans for the weekend. “We worry about long weekends and vacations the most,” she says. “And we worry because these kids will be making decisions about whether or not to pick up substances with lethal implications.”

Despite these and other efforts to keep students sober, relapses are frequent. “If I were to give you a percentage, maybe 40 percent to 50 percent come in after a weekend and have used,” Burke-Lewis says. She does not, however, see that as a sign that her school’s efforts are not working. “Recovery with this population is about stops and starts.”

Medical experts would agree. “I don’t think we can expect kids who’ve been severely addicted to drugs and alcohol to automatically become sober,” says Joseph Shrand, an adolescent psychiatrist and addiction specialist who serves on Independence Academy’s advisory board.

Dr. Shrand believes relapse should be treated not as a failure but as an opportunity to learn. “That’s where sober high schools can be really useful,” he says. “Some kids are going to relapse. How do you then use that as a way to help the kid not relapse a second time?”

Still, he’s quick to note that relapses should never be taken lightly. “The real problem with the one kid who is using over the weekend but can stop for the week is that [he or she] may trigger a kid who cannot stop,” he says.

Taron, a ninth-grader at Independence Academy, says he feels it when classmates start using again. “Some students aren’t serious about recovery,” Taron says. Tall, soft-spoken, and into motorcycles and music, Taron started smoking a lot of marijuana and spent several weeks in treatment. Since enrolling at Independence Academy, he’s been drug-free for seven months. “When we’re trying to have a recovery meeting and some kids aren’t taking it seriously, that gets on my nerves,” he says.

Data on just how effective recovery high schools are in helping students stay sober is complicated. Researchers would like to track two groups of students: those who leave a formal drug treatment program and attend a recovery high school, and those who leave treatment and attend a regular high school.

“The problem is we can’t ethically direct children down one road if that would mean depriving them of treatment,” says Andrew Finch of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., who studies recovery high schools.

With only 33 recovery high schools operating nationwide, however, it’s already the case that most teenagers exiting drug treatment will not get to attend a so-called sober high school. Researchers have been tracking how these adolescents have fared and have found that their relapse rates run from about 50 percent to 75 percent, depending on the study.

Are outcomes better for students attending recovery high schools? Dr. Finch is currently collecting and analyzing data on 293 teens who completed formal drug treatment, half of whom then went to a recovery school, the other half to a regular school. “Recovery high schools appear to have a positive effect on reducing alcohol and drug usage, relative to nonrecovery high schools,” Finch says of his preliminary findings.

In the case of some specific drugs, Finch says the effect was large. Six months after treatment, for instance, students at recovery schools had 17 fewer days of marijuana use compared with their peers at regular high schools.

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health’s 2011 study also found positive effects. On entering recovery schools, students reported using alcohol and marijuana – on average – one to two times per week. Upon exiting (graduation or returning to a regular high school), their reported average use had fallen to one to two times per month.

But if recovery schools are making a difference, too few students seem interested. State-run drug treatment centers in Massachusetts discharged more than 1,000 teenagers in 2016, according to Tom Lyons, director of communications for the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Only 116 students were enrolled in the state’s five recovery high schools as of early December. The same dynamic is playing out across the country.

Independence Academy, with 22 students, has room for twice as many. To some, low enrollment has a simple explanation. “I think we have to do a better job of letting families know that this option is available,” Carpenter, Brockton’s mayor, says.

To Finch, the explanation has to do with changes in education. “There are more options these days,” he says. “In some states, parents can choose from virtual schools, charter schools, home-school, and they may be choosing those instead of recovery schools.”

Others blame low enrollments on the way recovery schools handle treatment. Most embrace a 12-step model, similar to Alcoholics Anonymous, in which the first step is admitting “we were powerless” over drugs.

“It may be the reason why we don’t have more students in sober high schools, because their parents, their families, their school systems do not want to see their kids as somehow bad, defective, and deficient,” says Shrand, the psychiatrist.

Shrand also worries about the message this approach sends to students. “Many of these kids started using because they were worried they were broken,” he says. “Quite inadvertently, we run the risk of making them feel like they have less value, which is the exact opposite of what we want to do.”

• • •

One sure way to head off any debate is to prevent teenagers from developing addiction problems in the first place. Drug prevention and education usually fall to the schools. In response to the current opioid crisis, the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office is earmarking $500,000 for new school-based drug prevention efforts.

Brockton, too, is taking steps. “We have a certified health educator in every school building,” says Mary Ellen Kirrane, director of wellness for Brockton Public Schools.

Lessons start in kindergarten with “what is medication?” Drug prevention continues in middle and high school. “We talk about choices and decisions and peer pressure, and we talk to students about getting help,” says Ms. Kirrane. Every student participates in classes like this for a half-hour each week.

Brockton pays for drug prevention on its own because state and federal grants – once as much as $500,000 each year – disappeared long ago. Even though Brockton has one health teacher for every school, Kirrane says that’s actually down from two or three per building when she became the health director here in the early 1990s. Still, she feels fortunate. “When we look at other school systems, we’re like the Cadillac version,” Kirrane says.

The US may need more than just health teachers, though, to stem the crisis. Of the 1.3 million teenagers in the US with drug-abuse problems in 2014, some 340,000 – or 28 percent – also reported having a major depressive episode in the past year. Experts such as Shrand would like to see more child psychiatrists available as well.

Langley, meanwhile, is striving to overcome his addictive urges every day. “The thing about my disease is it’s a selfish disease,” he says. “You put anything in front of me – weed, coke, whatever – and I’ll do it. Once it’s in front of my face, everything just goes out the window.”

Langley has a few months left in the halls of Independence Academy to shore up his defenses: He graduates in the spring.

ρ This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.