Seattle's $15 minimum wage debate catches small businesses in the middle

Loading...

| Seattle

The posters on display at the entrance to her Capitol Hill store say it all: “You are safe here.” “Black Lives Matter.” “Resist Trump: keep America great.”

“I was raised on the most progressive politics,” says Jon (pronounced “Joan”) Milazzo, who co-owns Retrofit Home, a furniture shop on a busy corner of downtown Seattle. A native Vermonter who moved west about 30 years ago, Ms. Milazzo is all for the idea that employees – especially those at the bottom of the pay scale – receive a fair wage for their work.

But she is straining to reconcile her principles with what’s best for her business. Seattle’s 2015 minimum wage ordinance raises hourly pay by 50 cents to a dollar per year until all companies in the city hit $15 by 2021. Milazzo says she’d be happy to comply – if she didn’t also have to contend with soaring property taxes and rental and utility rates. Instead, she’s condensed her store hours and cut entry-level jobs.

“You can’t just say to the little people, ‘Now pay everybody more,’ ” she says. “Where does it come from?”

Seattle, among the first cities to adopt a $15-an-hour minimum wage ordinance, has been the setting for a debate over the effects of the policy so far. The dispute centers on two apparently conflicting studies, both released this year. One, from the University of Washington, found that the ordinance significantly reduced average earnings for low-wage workers throughout the city because employment opportunities declined. Another, from the University of California, Berkeley, found that job loss – specifically in the food service industry – was minimal, and that wages indeed rose for workers making the least.

The opposing results have driven a deeper wedge between advocates and opponents of the $15 wage. Each side has pointed to flaws in the offending study and used the supportive research to back their cause.

Conversations with those whom the policy affects, however, suggest the issue is not so cut-and-dried. In deeply liberal Seattle, small business owners like Milazzo acknowledge the benefits of paying workers well, both for their employees and the businesses themselves. Still, they worry that their own enterprises won’t survive the rising costs of doing business in the city. Low-wage workers, meanwhile, celebrate the march to better pay, noting that in Seattle even $15 an hour is barely enough to get by. But they recognize that not every company can easily make the change.

Everyone frets about rent.

“Public opinion polls are strongly behind [the $15 minimum wage] and small business polls show they are also in support of it,” says Paul Sonn, general counsel and program director for the National Employment Law Project, a nonprofit based in Washington, D.C. “They think it’s fair. They’re concerned about inequality. The question is just how do you phase it in.”

'A big difference'

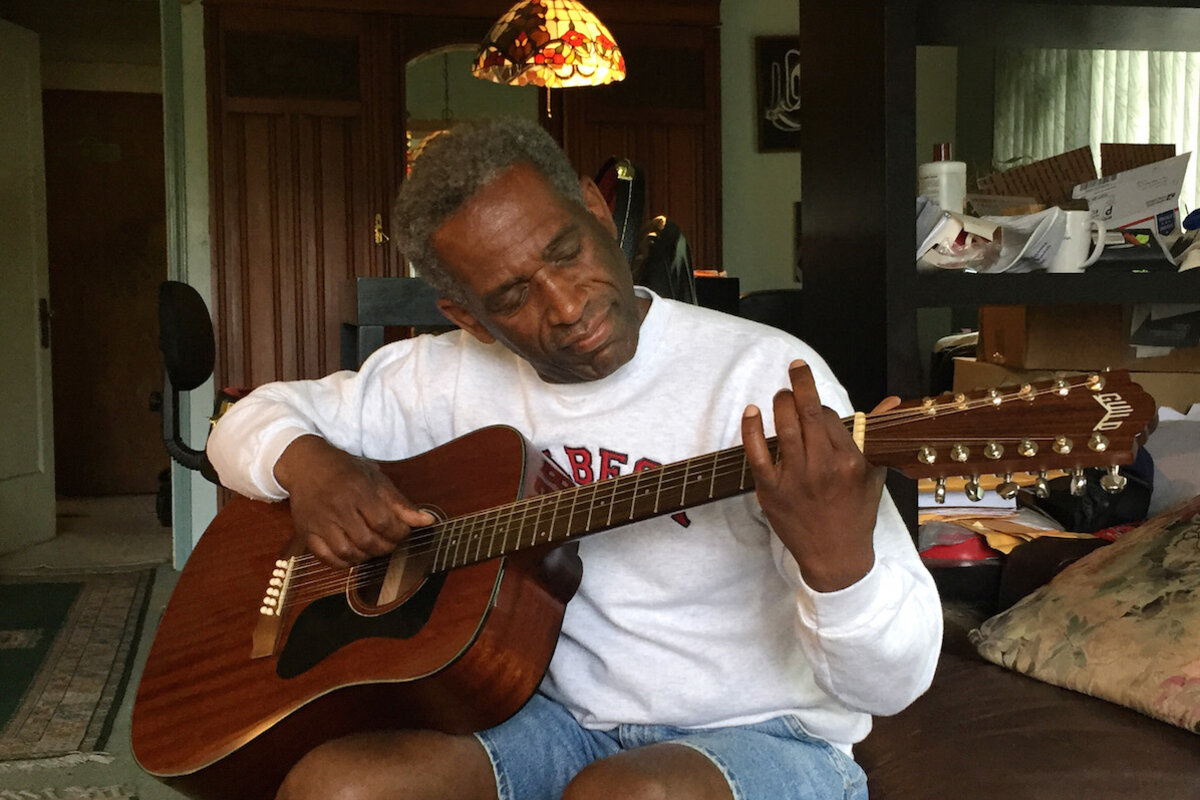

When Jerry Cole talks about his job, a note of quiet pride creeps into his voice. “I’m that person that bags your groceries,” he says, describing his duties as a courtesy clerk at Safeway. “I’m that person that keeps your restrooms clean. I’m the person that brings in the shopping carts when it’s time to get them inside so that when you come in, there’s one available for you.”

For these tasks, which he performs about 30 hours a week, Mr. Cole receives $13.50 an hour. “It’s a big difference,” he says, from the roughly $9 an hour he was making when he started at Safeway five years ago.

For workers like Cole, the policy has meant a tangible improvement in their quality of life. Their experiences support the idea that stagnant wages hurt the economy – and that raising them helps both employers and employees.

Zac Lawrence says he sighed with relief when he received his first bi-weekly paycheck after the city implemented the $13-an-hour phase of its minimum wage hike. “I’m used to hoarding my tips … because you never know if you’re going to have a bad week,” says Mr. Lawrence, who works two restaurant jobs while he tries to build a career in political consulting and outreach. “That was the first time I was getting an actual paycheck and could say, ‘This can pay for half of my rent.’ ”

Now, he says, he feels more secure. And in his neighborhood, populated by service industry workers, business is thriving, he adds. “We have more money to spend,” Lawrence says.

Cole, at Safeway, observes that the policy isn’t perfect. He can see why some employers feel the need to cut back on hours and jobs. “Everyone can’t pay $15, particularly small businesses. I get that,” he says. But as someone who almost never takes a sick day, shares a single-family home with eight other people to save on rent, and runs a landscaping business as a side job just to get by, Cole can’t defend big business keeping wages low.

“We’re still underpaid, quite frankly,” he says, sitting among the books and bric-a-brac that imply shared habitation.

Incentives for everyone

Milazzo, of Retrofit Home, sits perched atop one of her sofas for sale. For years, she says, she and her business partner would hire teenagers at entry level, training them in both the nuts and bolts of the business and a meaningful work ethic.

But as higher rents and rising taxes converged with the new minimum wage policy, Milazzo says she was forced to trim her staff and use fewer resources on training beginners. “The water level was going up all around us,” she says. “So we made that decision. When you come in, you’ve got to have skills.”

Even the most liberal business owners express a sense of being squeezed on all sides.

Felix Ngoussou, an immigrant from Chad who teaches business courses to aspiring entrepreneurs, started out advocating the $15 minimum wage. He preached the benefits of better wages. “People have to have a decent wage so that they can make a living,” he says.

In 2013, Mr. Ngoussou opened a café called Lake Chad in central Seattle. As the minimum wage ordinance took effect, he found himself at a loss for workers. Wage obligations under the Seattle law vary according to business size, and Ngoussou is currently required to pay about $12 an hour.

“People prefer to go drive Uber, go work at Amazon or the airport at $15 an hour, than working in a small coffee shop for $12 or $13,” Ngoussou says. “There are people standing out there saying, ‘Oh if you don’t pay me $15 an hour, I don’t take the job.’ ” Unskilled workers would start at Lake Chad and then, once trained, would hop down the street to Starbucks for its higher wages, tuition reimbursement program, and paid sick and family leave, he says.

“I used to have four to five employees,” Ngoussou says. “Now I don’t have even one.”

Ngoussou has since revised his position: Government should raise wages – but also find ways to control rent and lower taxes for smaller businesses. “We need it to come with a package that offers some incentive to everybody, to small business owners and to employees,” he says.

'A cautionary tale'

Seattleites’ varied experiences with the city’s minimum wage ordinance reflect a key fact that researchers keep coming back to amid the economic theories, political debates, and conflicting studies: There’s still plenty the experts don’t know.

One thing researchers want to explore is how exactly the policy will play out in different cities – and who ultimately reaps the benefits. For instance, “Just because we found that on average workers lose, that doesn’t mean every worker loses,” says Bob Plotnick, one of the authors of the UW paper. If teenagers and retirees are mainly the ones losing low-wage work while heads of household are seeing a net gain in their income, “most people might be OK with that,” he says.

“We think of this as a cautionary tale,” Mr. Plotnick adds. “If a city is going to implement a minimum wage that is substantially above the federal level, it needs to think carefully about what the impacts might be.”