In Schneiderman case, signs of a broader ethical dissonance

Loading...

| Savannah, Ga., and Boston

Hypocrisy-laced scandal, of course, belongs to no particular party. But the case of former New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, who resigned this week after four women accused him of assault, has given insight into a growing recognition of the damage that hypocrisy can inflict, in part because it uses other people’s humanity and trust as weapons against them. Previously, Mr. Schneiderman had fashioned himself as a champion of the #MeToo movement and lashed out in speeches at the immorality of men using their power to subjugate and control women. “It’s an emperor’s-new-clothes moment,” says Ruth Grant, author of “Hypocrisy and Integrity.” It isn’t just the allegations of violent acts themselves that shock the public conscience, but the dishonest signaling that accompanies them, says Jillian Jordan, who studies the origins of human morality at Yale University. “When people find out that Eric Schneiderman privately is acting completely inconsistently with the public image he’s created, they think ‘OK, one, the thing that you did is bad, but, also, your public advocacy was deceptive and misleading and earned you a false reputation,’ ” says Dr. Jordan. “We don’t like that. We think it’s unfair.”

Why We Wrote This

The assault allegations against the former New York attorney general disquieted many Democrats – as did reports that the women were urged not to reveal the abuse because it could hurt liberals' goals. The alleged violence and the reaction to it highlight a broader ethical dissonance in American society.

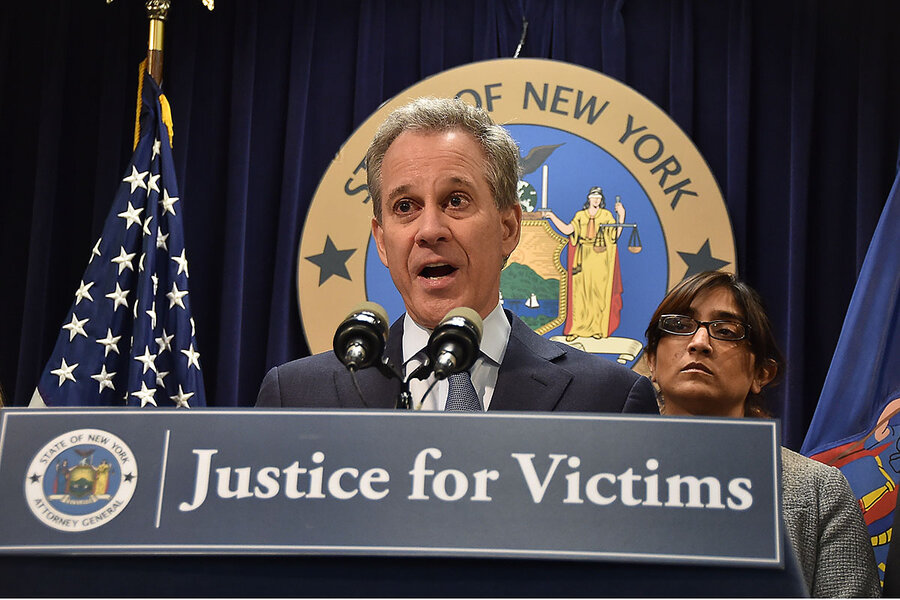

Allegations that now-former New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman led a double life where he championed women by day and mistreated them by night offered Americans this week a disquieting peek at the ubiquity of hypocrisy.

The latest in a long line of US politicians accused of abusing women behind closed doors, Mr. Schneiderman, a veteran prosecutor who cut his teeth in the Albany legislature, had emerged as a hero of women’s rights and a champion of the #MeToo movement. He resigned Monday amid allegations he hit and strangled romantic partners.

That this all happened in the liberal sphere delighted many Republicans, some of whom saw it as a gotcha moment for liberal pieties, especially as Mr. Schneiderman had gone to war against the Trump administration. For their part, liberals saw it as horrifying but also a suggestion that the #MeToo movement is working. New York Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D) has called for a criminal investigation. Democrats’ disquiet was heightened by the reports that some victims said their friends urged them not to reveal the abuse because it could damage broader political goals.

Why We Wrote This

The assault allegations against the former New York attorney general disquieted many Democrats – as did reports that the women were urged not to reveal the abuse because it could hurt liberals' goals. The alleged violence and the reaction to it highlight a broader ethical dissonance in American society.

The alleged violence and the reaction to it highlights a broader ethical dissonance where many Americans struggle, in large and small ways, with “the aspiration to uphold a moral self-image and the temptation to benefit from unethical behavior,” as researchers put it in a recent issue of Current Opinion in Psychology. For some at least, the Schneiderman case has inspired a humbling recognition of the damage that hypocrisy can inflict on people and society, in part because it uses other people’s humanity and trust as weapons against them.

For some, the Schneiderman case has given insight into what Polish dissident Czesław Miłosz described as “ketman.” In totalitarian countries, maintaining a public face that's completely at odds with one's private nature could be a strategy for success and even survival. In Western democracies, it's more commonly known as hypocrisy.

Now, the case is part of a growing recognition of the damage that hypocrisy can inflict on people and society, in part because it uses other people’s humanity and trust as weapons against them.

“It’s an emperor’s-new-clothes moment,” says Duke University political scientist Ruth Grant, author of “Hypocrisy and Integrity: Machiavelli, Rousseau, and the Ethics of Politics.”

Four women told The New Yorker’s Jane Mayer and Ronan Farrow that Schneiderman physically assaulted them while they were in romantic relationships. He allegedly broke one woman’s eardrum, and multiple women say he strangled them. He also threatened the women if they spoke up, they said. “I am the law,” he reportedly told one.

Only weeks earlier, he had said, “protecting New Yorkers from domestic violence – and the housing and job discrimination that victims often face in the wake of such abuse – is a key part to stopping the cycle of violence in our state and our nation.” He has also lashed out in speeches and statements at the immorality of other men using their power to subjugate and control women.

Now Schneidermann is being investigated for violating an anti-strangulation law that he himself sponsored while in the state Senate. He has called his actions “role play” that did not interfere with the execution of his state duties. “In the privacy of intimate relationships, I have engaged in role-playing and other consensual sexual activity. I have not assaulted anyone. I have never engaged in nonconsensual sex, which is a line I would not cross,” Schneiderman has said in a statement.

But it isn’t just the allegations of violent acts themselves that shock the public conscience, but the dishonest signaling that accompanies them, says Jillian Jordan, who studies the origins of human morality at Yale University.

“When people find out that Eric Schneiderman privately is acting completely inconsistently with the public image he’s created, they think ‘OK, one, the thing that you did is bad, but, also, your public advocacy was deceptive and misleading and earned you a false reputation,’ ” says Dr. Jordan. “We don’t like that. We think it’s unfair. You don’t deserve to be seen as good if you’re not good.”

Hypocrisy-laced scandal, of course, knows no particular party.

Republicans Blake Farenthold, Trent Franks, and Pat Meehan have bowed out of office under clouds of sexual misconduct, at times contrasting with stated beliefs in family values. So have Democrats Al Franken, Ruben Kihuen, and John Conyers, who professed support of women’s causes. Scandals have ensnared a number of high profile entertainers. Schneiderman, in fact, sued former movie mogul Harvey Weinstein. More than 50 women have accused Mr. Weinstein of abuse ranging from rape to sexual harassment, kickstarting the #MeToo movement. For his part, Weinstein has denied charges of nonconsensual sex and retaliating against women who turned him down.

‘Drunk with power’

The nexus of power, fame, and high-octane work environments also play a role: Leaders are often more likely to chide members of their flock for immoralities that they, themselves, indulge.

“In general, we find that powerful people are more ‘free’ in their judgment decisions...,” says psychologist Joris Lammers, who studies the interplay between moral reasoning and immoral behavior at the University of Cologne, Germany, via email. “It is at least partially an automatic effect [which means] there is also a more uncontrolled element to it. You can compare this to the effects of alcohol. In many ways, the phrase ‘drunk with power’ is true, psychologically speaking.”

Some Republicans, including President Trump, have questioned the veracity of allegations leveled against people like Alabama Senate candidate Roy Moore and former White House adviser Rob Porter, highlighting the need for due process for those accused. In Missouri, Republican Gov. Eric Greitens has refused to resign even after facing criminal charges in a sexual blackmail scandal. The Republican-led legislature is convening a special 30-day session May 18 to consider whether to impeach him.

Much of the measure of scandal and the direction of public scorn is the extent to which an alleged perpetrator has condemned others for doing the same thing.

Dr. Jordan and her colleagues have found that hypocrites typically invite greater scorn than those who commit straightforward moral infractions. “Someone who commits a moral transgression will be seen more negatively if they also condemn somebody else for the same transgression than if they just said nothing at all,” she says.

Democrats, meanwhile, have been quick to cut ties with those seen to be overstepping ethical bounds, some even before a hearing.

“There’s two ways to look at the political divide: One would be that the two parties have sincerely different positions about women’s rights and the other ... is looking at coalitions that the two parties are trying to build,” says Jim Battista, a political scientist at the University at Buffalo. “If you are trying to win over non-conservative women, part of how you do that is by ... not minimizing [these kinds of cases] or shielding people who seem to have done wrong. On the other hand, if you are not particularly fighting for [votes of] non-conservative women, you might see yourself as playing to your electorate by shielding people against those darn liberals.”

Women challenging assumptions

Research shows that while not everybody is a hypocrite, it is human to downplay, dissemble, and even simply forget one’s own ethical transgressions, especially those for which you have called out others. In fact, Daniel Effron and Paul Conway found in 2016 that “acting virtuously can subsequently free people to act less-than-virtuously.”

Much like the phenomenon of the ketman principle in totalitarian countries, Ms. Grant says that hypocrisy is also particularly common in liberal democracies like the United States, where fealty is paid to high moral ideals while the actual conditions are tied more to power and political pragmatism.

To Professor Battista, the dynamics of the Schneiderman case underscores that “there are a lot of ways in modern American society that we expect women to take this hit and take another hit and keep taking a whole bunch of other hits throughout life for the asserted benefit of someone else.”

For women more broadly, it may also be a time of greater introspection – and challenging assumptions, says Grant. She says the push to call out hypocrisy even if it spotlights your own individual or group’s flaws has already crossed partisan lines. Criticism is mounting around the Rev. Paige Patterson, the president of the Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas.

When it emerged last week that Mr. Patterson had suggested that the Bible says that married women should endure domestic violence and that it is OK for men to ogle teenage girls, more than 2,000 Southern Baptist women signed a letter calling for his removal from leadership, citing an “unbiblical view of authority, womanhood and sexuality.”

In their view, the issue has to be dealt with not just individually, but as a congregation coming to terms with fundamental beliefs – an honest soul searching.

“We’re trying to offer this correction in love because we are a body,” the women wrote to the Southern Baptist Convention. “That’s what we believe as Christians. And we need to correct one another and spur one another onto good deeds. And that’s what we’re trying to do with this letter.”