Drinking water in short supply? There’s a solution in the air.

Loading...

| Malibu, Calif.

There’s an urgent need for access to water – and innovations are at work to adapt an ancient technology for modern use. Atmospheric water generation is based on laws of condensation: Warm air meets a cool surface and forms water droplets. But these water harvesting systems are still relatively small and expensive, not yet practical for providing large or consistent water supplies.

Activists, researchers, and the U.S. government are committed to changing that. “In not too long, you will see these machines in areas where we most need them,” says Omar Yaghi, a chemistry professor at the University of California, Berkeley.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onAs the world gets drier and hotter, reliable access to water is becoming a greater challenge – lending urgency to innovations that could provide water anywhere in the world, pulling it right out of the air.

Dr. Yaghi has invented a lightweight, compact grouping of minerals and organics called metal organic frameworks that are highly absorbent and whose water can be quickly released with nothing more than ambient sunlight. Most atmospheric water harvesters only work in areas with high humidity. But MOFs also work in low humidity – in arid places such as his native Jordan.

The U.S. military’s Defense Advanced Research Project Agency is working with him and other researchers to develop water systems that can be tapped anywhere, so service members won’t have to rely on supply chains for drinking water. “We’re cautiously optimistic we’re on track” to produce a prototype in two years, says Seth Cohen, a DARPA program manager.

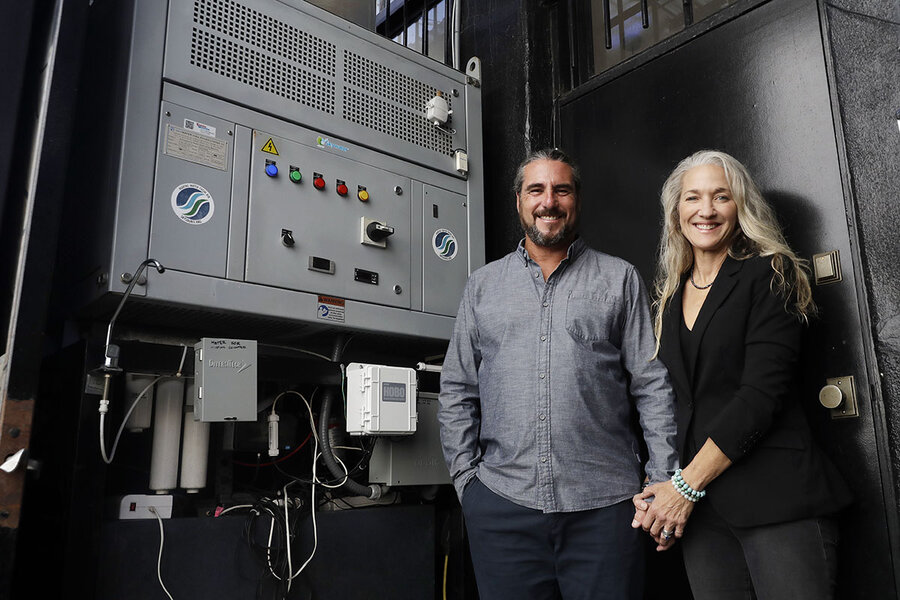

In June, 6 million people in Southern California began unprecedented water restrictions due to severe drought, with lawn watering limited to one day a week in many areas. But that doesn’t apply to David Hertz and his wife, Laura Doss-Hertz. High above the Pacific Ocean, tucked in the steep contours of mountainous Malibu, they supply their house, pool, and network of firefighting hoses with water harvested from the air.

The couple use their property – dubbed Xanabu – as a demonstration site for atmospheric water generation. Their small farm, where coffee plants and passion-fruit trees are irrigated from well water, is an idyllic spot. Blooming pink, red, and white oleander line the winding driveway, a mass of hot pink bougainvillea climbs their stone chimney, and dramatic views stretch to the ocean and surrounding mountains. Colorful pagodas from the movie set of “The King and I” add a magical touch.

But there is nothing magic about the science of their water-generating product, called WeDew. It’s based on the laws of condensation – warm air meets a cool surface and forms water droplets. Through their company, Skysource Inc., they’ve taken ancient, passive techniques and used sustainable-energy innovation to increase water output, winning the $1.5 million Water Abundance XPrize in 2018. Out of nearly 100 entries from around the world, theirs was the only one to meet all the criteria: Produce at least 2,000 liters (528 gallons) of water a day, at a cost of less than 2 cents per liter and running entirely on renewable energy.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onAs the world gets drier and hotter, reliable access to water is becoming a greater challenge – lending urgency to innovations that could provide water anywhere in the world, pulling it right out of the air.

“All we’re really talking about is very simple,” says Mr. Hertz. He swings open doors to a 20-foot shipping container that holds the air-to-water generator near his house. He likes to remind people that the Earth and its atmosphere are a closed system with a set amount of water that changes form as liquid, vapor, and ice. “There’s six times more water in the atmosphere than all the rivers on the planet,” he says. “The real challenge is how do you capture this available moisture?”

The historic drought in the Western United States is adding urgency to this question. Federal water officials recently warned that major cuts in usage will be required next year for the Colorado River, which serves nearly 40 million people in the West. The 22-year drought, exacerbated by climate change, is the region’s worst in 1,200 years. Globally, 1 in 3 people do not have access to safe drinking water, according to the World Health Organization.

This urgency is driving support for innovations in atmospheric water generation to address the two biggest hurdles to widespread use: scaling it up, and making it accessible – and affordable – to people in regions that need it most.

Planning ahead

Those innovations are being explored at Tsunami Products in Liberty Lake, Washington. Inquiries about its atmospheric water generators shot up 1,500% in the month after The Associated Press published a story about it last October, says Mark Fralich, who handles marketing for the privately owned company. “Inquiries have not let up,” says Mr. Fralich, who is fielding 10 to 50 calls, voicemails, and emails a day, and serving customers from California to Texas to the Cayman Islands and South Africa. The company says its products can be used for homes, offices, schools, and greenhouse irrigation, and as backup water supply.

The plug-in units look like tall air conditioners, pulling in moist air, condensing it, storing the water in an internal tank, and then purifying it. But certain temperature and humidity conditions are needed “to create Mother Nature’s ambient dew point,” says Mr. Fralich.

The optimal environment is an average temperature of 80 degrees Fahrenheit and humidity that is 80% per a 24-hour day, explains Mr. Fralich. That’s when Tsunami’s smaller unit can produce up to 204 gallons of water per day, and its larger unit can produce up to 329 gallons per day (an American uses an average of 82 gallons per day at home). The units are not cheap, ranging from $35,000 for the smaller one to $65,000 for the larger size.

One of the people who read that AP story was Jerry Hudgins, a retired software engineer in the Northern California coastal town of Point Reyes Station. Water consciousness is a way of life in this area, where water restrictions are on the books year-round and get tighter when rainfall is even scarcer. Mr. Hudgins bought the smaller unit, installing it on a concrete slab next to his house. He wanted it as a water backup in case of an earthquake and also for the gardening design business of his wife, Suzi Katz. Her demonstration garden covers most of their nearly 1-acre property, and they are concerned that the current drought – and restrictions – will worsen.

Mr. Hudgins knows that they live in a less-than-ideal area for maximum water output. They get a fair amount of coastal fog and humidity, but temperatures are cooler than in other parts of California. That makes it harder to condense water. Also, they are not running the system at night to spare their neighbors the noise. So far, he’s generating what he expected – about 50 gallons on a warm day.

The couple are using utility water to irrigate Ms. Katz’s garden until expected restrictions kick in later in the summer. In the meantime, they’re building up water in their storage tank, which cost extra. Installing the system “was an expensive proposition and it took a lot to set up,” he says. “But ... we would do it again.”

Practical solutions?

Atmospheric water generation is good for rural areas that are far from water infrastructure, and for use in relatively small amounts, such as for drinking, says Heather Cooley, director of research for The Pacific Institute, a global water think tank in Oakland, California. It takes a lot of energy to bring air to the point of condensation, she says. The industry is in its nascent stage, and several people interviewed for this story warned of charlatans promising the impossible and even fake companies.

“There are opportunities there, but I also think we need to look at other strategies that are available, and widely available,” says Ms. Cooley. In April, The Pacific Institute published a report on California’s urban water supply. The report found that greater efficiency could reduce use by 30% to 48%, and water supplies could be boosted by more than doubling municipal water reuse and significantly increasing stormwater capture across the Golden State.

Omar Yaghi, a professor of chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley, believes that atmospheric water generation is “the way of the future,” putting individuals “in control of their own drinking water.” He sees potential applications in everything from residences to irrigation of small-scale farms. The only thing holding back faster innovation is skepticism, he says. “People who invent game-changing things, the biggest problem they face is always doubt. It’s very easy to say no.”

Dr. Yaghi has invented a lightweight, compact grouping of minerals and organics called metal organic frameworks, or MOFs, that are highly absorbent and whose water can be quickly released with nothing more than ambient sunlight. Most atmospheric water harvesting products only work in areas with high humidity – as in coastal or tropical areas. But MOFs also work in low humidity – in arid places such as his native country of Jordan.

An MOF device that could produce 500 liters (132 gallons) a day in the desert would be about the size of a small automobile, though not as heavy, says Dr. Yaghi. He’s working on cutting that size in half. “In not too long, you will see these machines in areas where we most need them.”

“We know there’s enough water”

Dr. Yaghi has the financial support of the U.S. military’s Defense Advanced Research Project Agency. DARPA is working with him, General Electric, and other U.S. companies and universities to develop water systems that service members could use anywhere in the world, without logistical supply chains.

“We’ve seen some really encouraging data,” says Seth Cohen, program manager for the Biological Technologies Office at DARPA. “We’re cautiously optimistic we’re on track” to produce a prototype in two years. “We wanted to get past the dehumidification technology. We wanted to go to the next type of technology that we think will be a breakthrough using absorbent materials.”

Back at his hilltop paradise, Mr. Hertz, an architect by trade, explains how his mobile, shipping-container water generator also produces energy. WeDew doesn’t need diesel or electric power because it runs on biomass – in this case, wood chips from clearing brush. A gasifier superheats the wood chips and converts them into electricity, hot humid air (which condenses to water), and carbon-capturing biochar. He stores the electricity in batteries to power his house, and he uses the biochar to replenish his soil. “It’s a virtuous cycle.” That virtue was recognized in 2020, when Time listed WeDew among the magazine’s 100 best inventions.

Skysource has teamed up with the United Nations World Food Program to bring WeDew to Uganda and other countries. Now the company is in discussions with the U.N. to serve island nations, where rising sea levels are causing saltwater incursion in fresh water. Closer to home, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection is using WeDew in forests in the northern part of the state because of biochar’s fire-suppressing capability, says Mr. Hertz. He says WeDew works optimally for small communities that need clean drinking water, as emergency power and water, or on small ranches like his.

Like Dr. Yaghi, he’s optimistic about the future of atmospheric water generation. “We know there’s enough water. It’s just a question of how do we appropriate it in a responsible way.”