Building Men teaches students what manhood can really mean

Loading...

| Syracuse, N.Y.

When Joe Horan went through a divorce he came to a startling personal realization. He had been chasing a definition of manhood that was prized by society but that felt superficial and misguided.

His life, he says, lacked substance and depth. Chasing money, women, and sports held outsize significance. He wanted to “find healing from the unhealthy messages I believed about masculinity.”

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onJoe Horan felt that society’s definition of masculinity was leading him down the wrong path. So he built a positive vision of manhood not just for himself, but also for the teenagers he mentors.

A physical education teacher at the time, Mr. Horan saw young boys around him embarking on a similar path and sought to offer a broader, more positive idea of manhood.

Through fellowship with male peers and mentors, his Building Men mentorship program has helped more than a thousand students gain perspective, work to restore self-worth, and learn to calm emotions. Kids participate in community service and mentor-led talks to help students navigate the stresses of adolescence.

A basketball component offers an accessible entry point for many students, but the program’s secret is how it dives into off-the-court issues through reinforced discussions on character.

“They sign up because they want to play basketball,” Mr. Horan says. “By the end of the year, they can better define their journey and a vision of their masculinity.”

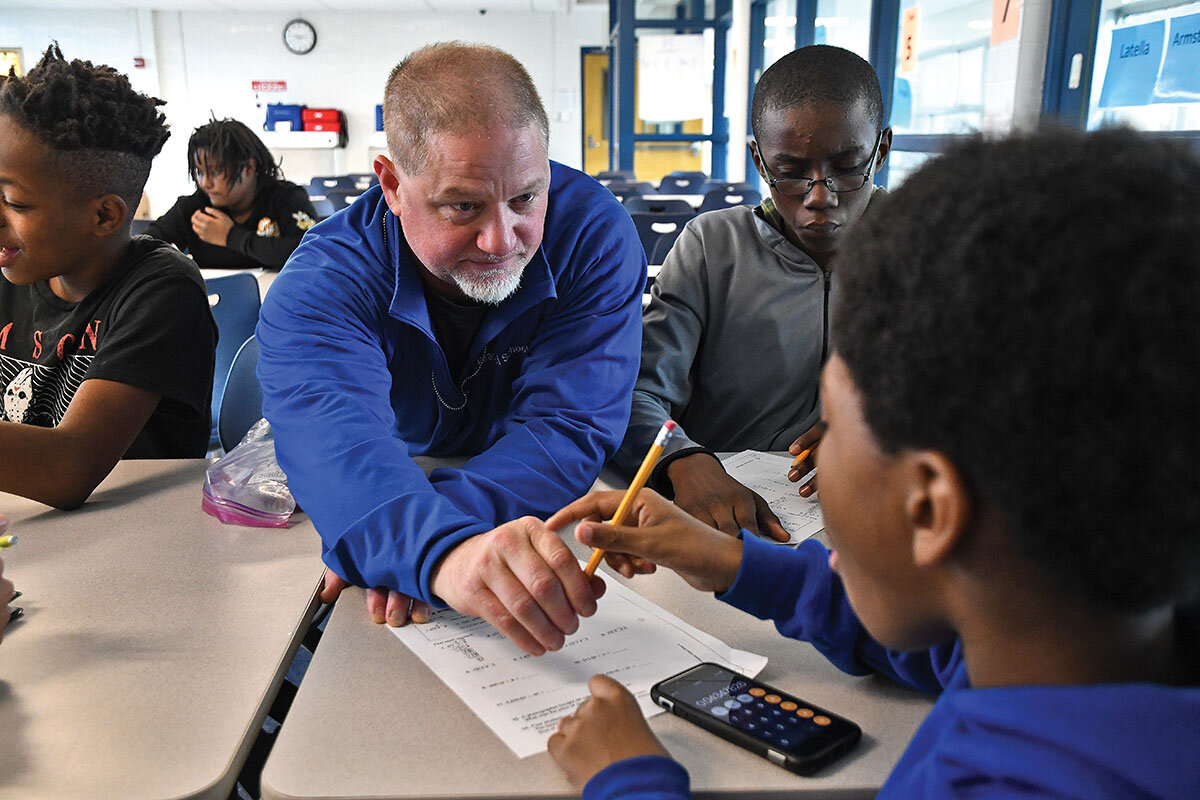

On a recent Tuesday, an after-school session for sixth- through eighth-grade boys starts in a second-floor cafeteria. Today’s lesson: attentive listening.

Samuel Colabufo, whom the young men call “Captain C,” asks the nine students to recite the Building Men creed. A few rattle it off with confidence, but many have just begun the program, an initiative of more than 15 years that has guided more than a thousand boys in the Syracuse City School District through a combination of mentorship, character building, and sports.

Eighth grader De’Kota White, who has been involved for two weeks, does not yet have the 16-line creed memorized. He learned about the program during an opening-year assembly where Building Men’s founder, Joe Horan, spoke. De’Kota wanted to join because it sounded fun.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onJoe Horan felt that society’s definition of masculinity was leading him down the wrong path. So he built a positive vision of manhood not just for himself, but also for the teenagers he mentors.

“They do a lot and you get a chance to plays games at school,” he says. He looks forward to field trips, and by the end of the school year, attending the Rite of Passage – a culminating activity to prepare middle schoolers for their transition to high school.

Mr. Horan, who’s worked in the district for 30 years, says in an interview that the various elements of Building Men may seem small from the outside, “but aren’t small to the individuals involved.”

A personal journey

Looking back, Mr. Horan says his program evolved from a low point in his life. In 2004 as he went through a divorce, he realized he was chasing society’s definition of manhood. His life, he says, lacked substance and depth. “A desire became planted in my heart ... to find healing from the unhealthy messages I believed about masculinity,” he says.

These unhealthy messages, or what he calls the “lies of manhood,” crystallized after his sister recommended a book about Joe Ehrmann, a former NFL player and a motivational speaker. The book, “Season of Life” by Jeffrey Marx, delves into Mr. Ehrmann’s revelatory discovery of what being a man is all about. He identifies three myths: chasing money, having all the girls, and being a sports star. All three, Mr. Horan says, were also his sole sources of validation.

At that time, he worked as a middle school physical education teacher. During one class, he wondered how he could help his students avoid such traps. “These guys are going to have the same problems if someone doesn’t teach them another way,” he thought. “I asked myself, how can I challenge the boys’ thinking about the assumptions given to them by society on what a ‘real man’ should be?”

He took Mr. Ehrmann’s cue and started to implement life lessons into his class.

Building Men began at one middle school in the district in 2006 and grew on a shoestring budget, expanding school by school, year by year. For the first time this year, it’s being offered to fourth and fifth graders at seven different elementary schools. The program appeals to boys because of a basketball component, but its secret is how it dives into off-the-court issues through reinforced discussions on character.

“They sign up because they want to play basketball,” Mr. Horan says. “By the end of the year, they can better define their journey and a vision of their masculinity.”

A turning point for one student happened during the Rite of Passage camping trip. “When things wrapped up around 9:30 p.m.,” Mr. Horan recalls, “unbeknownst to me, one eighth grader had called our school’s ELA [English language arts] teacher.”

In that call, the student told her he needed to change. By the following Monday, the young man, who excelled as an athlete but put limited effort in class work, started to spend every lunch period with her for tutoring. “He went from 60s in all his classes, to passing with a 90 in ELA,” Mr. Horan says.

“Something happened on that Rite of Passage,” Mr. Horan says. “Something ... clicked for him that made him say, ‘I need to change my life.’”

Creating fellowship

Today, 33 lead coordinators, like Mr. Colabufo, work across 18 schools – more than half of those in the district – to lead sessions based on Mr. Horan’s curriculum.

This is Mr. Colabufo’s first year as a lead coordinator, a part-time position, though he taught in the district for 25 years. He’s known Mr. Horan for several of those years, noting many people are aware of the program’s success. “Joe’s a legend in this district,” Mr. Colabufo says.

By creating a fellowship of male peers and mentors, Building Men helps participants gain perspective, work to restore self-worth, and learn to calm emotions. The acronym SIR is a central component of lessons, standing for significance, integrity, and relationships.

Other key components include inspirational speakers, regular community service, and holding “chalk talks,” which Mr. Horan created to help students navigate adolescence. Humor and fun are also key.

The district’s interim Superintendent Anthony Davis says he’s told by teachers that students in Building Men “carry themselves differently” and engage adults with respect.

“They stand out,” Mr. Davis says, “because they have a positive impact. I want to spread that impact of this program across the district.”

In the 2021-2022 school year, Building Men reached 318 students with a self-reported attendance rate of 80%. The program’s participants have a 77% rate of graduation, according to data from that same year school year, compared with the district’s graduation rate of 71% overall.

Since 2017, Mr. Horan has served full-time as the program’s executive director, a role funded by the district. Some overtime is paid by Building Men. Other program costs, including staff salaries, are covered by outside grants and private donations. The school district offers space for the sessions free of charge. Mr. Horan says there is enough funding for most of this school year, but he is still raising more for end-of-year programming.

At a recent breakfast fundraiser, Shateek Nelson, a senior at Nottingham High School, shares his experience, having participated in Building Men since middle school.

He says he learned to see the bigger picture, rather than living in the moment. He also came to realize his actions affect others, and now he factors that into his decisions. “I would hate for my mom to cry at night because I was on the wrong path,” Shateek tells the audience.

Sustaining the program and ensuring its future is a daily priority for Mr. Horan.

“I have come to learn and experience that Building Men was created for a greater purpose,” he says. “I’ve learned I have to step out on faith.”