Florida woman kills wild boar with mango. (This is not a meme.)

| PINELAND, Fla.

Carol Etscovitz knows the exact moment she transformed into a Florida woman: the night she killed a boar with a mango.

She’d just been wandering through Promised Land, the name of the 300-tree, 40-acre property she owns with her husband, David. Their tract of land is tucked away in the subtropical vegetation of Pine Island, Florida, a massive, mangrove-ringed barrier island just off Cape Coral on the state’s Gulf side.

It’s full of razorbacks. Hundreds of boars and sows roam Pine Island, scrunching their snouts into burrows and feasting on fermenting fruit. Locals often patrol the island, sometimes shooting, sometimes trapping dozens of these feral pigs to get rid of them. (It’s legal to hunt and kill wild boars year-round in the Sunshine State.)

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onFlorida calls itself a bulwark of freedom. That’s one reason so many move here. Others find it repressive, and are ready to leave.

For the Etscovitzes, it’s just a hint of old Florida’s wildness – and just what they were looking for when they moved here from Hampstead, New Hampshire, in 2015.

But they were also seeking something less tangible, and harder to put into words: a sense of freedom.

Florida has emphasized its promises of freedom over the past few years. In July, the state unveiled new highway signs that read, “Welcome to the Free State of Florida.”

Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis, too, often proclaims the state a “liberty outpost” when comparing it with others, particularly those led by Democrats. “While so many around the country have consigned the people’s rights to the graveyard, Florida has stood as freedom’s vanguard,” the governor said in his State of the State address in 2022.

There’s a certain irony in the fact that the Etscovitzes left New Hampshire, the “Live Free or Die” state. The libertarian Cato Institute ranks it America’s freest. The Washington-based think tank ranks Florida the second-freest state.

Like a lot of transplants from up north, they were seeking to escape the cold and snow. Mr. Etscovitz says he was tired of being “stuck watching the wall all winter.”

Taking on Promised Land – and a wild boar

They didn’t find Promised Land right away. The Etscovitzes first purchased a property in the unincorporated Myakka City area in central-western Florida.

The land was far enough inland so they could afford sufficient acreage to graze their goats, which they turned into an all-natural weed-whacking business. To their delight, they were just an hour from the beach. It was, almost, everything they ever wanted.

But Florida’s economy was churning, and the area began to change. Hundreds of homes sprang up nearby, changing the character of their dream spot. What had once been an easy jaunt to Gulf beaches became a traffic-choked slog.

After living in Myakka City for seven years, they sold the property even before they found a new place. With just days before they had to vacate their herd from the Myakka City property, they decided to cross the bridge into Pine Island on a whim.

They drove past the colorful fish shacks of Matlacha. They smelled the salt in the prevailing westerly winds. That’s when Mr. Etscovitz spotted a rutted road through the vegetation. He said to his wife, “Let’s go down here.”

They found the Promised Land property. When Mr. Etscovitz asked the owner whether he knew about any property for sale on Pine Island, he said, “Funny you should ask.”

“I knew we had found where we belong,” Ms. Etscovitz says.

After they purchased the mango grove in 2022, she loved to wander through their new property. A few months after they moved in, she had her first face-to-face encounter with one of Pine Island’s feral pigs.

She was taken aback by its size and lack of fear of her presence. “Whoa,” she remembers thinking. “What’s up with this thing?”

“It was fall. It was pitch-dark and I had a flashlight, and this was a big pig,” she says. “And they will kill you and eat you.”

But what she remembers feeling wasn’t so much fear. She almost felt insulted by its insouciance as it rooted in her grove.

“I was mad,” she says. “Here’s this thing that doesn’t belong here, and he should be running away from me. Dave’s inside; he can’t hear me. I’ve got to deal with this pig.”

So she grabbed a mango that was pretty solid. “I picked it up and whipped it,” she says. Bop. Her aim was true. Bell rung, the creature rushed headfirst into a pond. The next day they found the boar, dead, its hams jutting just above the water.

“I have the worst aim on the planet, so this was an inspired hit,” she says.

The Etscovitzes make a modest living selling mangoes, honey, and chutneys. They have 40 goats, a 31-year-old horse, and a donkey on the property, as well as tortoises and turkeys. They invite their guests to interact with them.

It’s a struggle, actually, but it’s part of the sense of freedom they were looking for. Indeed, as an emblem of freedom, Mr. Etscovitz says, the grove isn’t about perfection, but about living one’s life intentionally, without judgment or interference.

For all its faults, he says, Florida has provided that space for their understanding and self-exploration. Personal freedom is coupled with what he and his wife are practicing at Promised Land: stewardship of both a historic grove and a way of living.

And that, Mr. Etscovitz says, is rooted in a sense of ownership, responsibility, and self-awareness that stretches beyond one’s property and impacts society more broadly.

“When people get in their element, they get happy, whether it’s on the water or anything,” he says. “I see so many people come down here: They do this; they do that. The people who are really having a good time are the ones that keep going.”

“This is a slice of old Florida,” he adds. “I just hope we can keep it.”

Florida has a rich history – and a quirky reputation

Florida has a certain reputation around the United States.

In Florida, mermaids hold government jobs as finned entertainers at Weeki Wachee Springs State Park north of Tampa. Not too far away in Land O’ Lakes, the annual Caliente Bare Dare 5K is billed as the largest clothing-optional race in North America.

It’s a place where strip malls with gun ranges and gentlemen’s clubs might include storefront houses of worship.

Florida is also the place where 100 Miccosukee refused surrender during the Seminole Wars in the mid-19th century. Avoiding capture and the infamous Trail of Tears, these Indigenous people disappeared into the Everglades. Today there are about 600 free Miccosukee, many of whom still live in “chickees,” thatched-roof houses on stilts within the Everglades, and near the tribe’s village on the Tamiami Trail.

“The free state of Florida” has long been a beacon of free expression, thought, and action. The first chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union south of the Mason-Dixon Line was founded here. Other leading lights include the environmentalist Marjory Stoneman Douglas and the novelist Zora Neale Hurston.

Florida elected the first Hispanic congressman, José Mariano Hernández, in 1822. It also sent the first Jewish man to the U.S. Senate, David Levy Yulee, in 1845. Representative Hernández was an enslaver, as was Senator Yulee, a secessionist who converted to Christianity.

“Florida is a paradox,” says Jack Davis, professor of history at the University of Florida and author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning book “The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea.”

“It is people reinventing themselves,” he says. “It offers tropical freedoms and dreams. But in certain particular behaviors and activities, there’s been a backlash.”

Governor DeSantis has turned what was a narrow mandate when he came into office “into a red bulldozer,” says Florida historian Steve Noll.

Taking a far more muscular understanding of the role of government, the two-term governor has in many ways helped redefine conservatism as he’s championed laws to limit access to books. He’s also taken on private businesses, signing into law restrictions on diversity, equity, and inclusion practices and critical race theory.

“DeSantis ... says that Florida is the freest state: You’re free to carry arms, free to move about with low taxes, all that stuff,” Mr. Noll says. “But for another set of people, it is definitely unfree.”

“People who come here don’t think that Florida has a history, that it starts with them moving across the state line,” says Mr. Noll, coauthor of “Ditch of Dreams,” a book about a failed cross-Florida canal. “That’s what makes this state so complicated.”

Florida’s history in many ways epitomizes the contrasting understandings of freedom that so divide the country as a whole today.

“I think a lot of this grandstanding against liberals – inviting them to leave if they’re unhappy with the state and of course not inviting them to come – is in fact working,” says Dr. Davis. “It’s turning the state of Florida increasingly red and moving away from the purple.”

For some residents, Florida’s brand of freedom has become stifling

For almost two decades, Paul Ortiz and Sheila Payne were two of the best-known community activists and scholars in Alachua County, Florida, and its largest city, Gainesville.

They’ve always thought a lot about the meaning of freedom. It’s their lifework, in fact.

Dr. Ortiz is a nationally recognized and award-winning scholar, and until this summer he was a professor of history at the University of Florida. He also directed the university’s Samuel Proctor Oral History Program, a position he had held since 2008.

Ms. Payne is a born-and-bred Florida woman. When she was 16 years old, she was the rodeo queen of Homestead, Florida. After years as a postal worker, she became a labor and fair housing activist, receiving recognition for her community service and winning numerous awards, including the 2022 Rosa Parks Quiet Courage Award.

The couple bonded after they were jailed together in 1995 during a farmworker protest in California. Dr. Ortiz jokes that the shared experience convinced them they could survive marriage together as well.

But as their home state of Florida started to become one of the most aggressive in the nation, restricting books and banning ideas, they decided they should leave.

This summer, in a kind of reversal of migration patterns, they packed their possessions and moved to New York, where Dr. Ortiz accepted a position as professor of history at Cornell University in Ithaca.

“Florida is very complex,” Dr. Ortiz says. “I love Florida, the community. We hate to leave it. But Governor DeSantis has made it clear that he doesn’t think that sociology or women’s studies are valid majors.”

The DeSantis administration calls its efforts to restrict books and ideas, especially those that focus on human sexuality and the experiences of people of color, as “freedom from indoctrination.”

But Dr. Ortiz sees these efforts differently. “In Florida today, shutting the school library down [so it can be inspected for banned books] is a version of freedom – the freedom to dictate,” he says.

It’s like living in “the upside down,” he says, referring to a 2022 court ruling that referenced the Netflix hit show “Stranger Things.” Florida has given the government the freedom to dictate what people can say and teach, even in private institutions.

In July, a federal judge issued a final ruling on a large part of Florida’s controversial “Stop WOKE Act,” declaring it a violation of the First Amendment. The 2022 law had limited private companies from using diversity, equity, and inclusion practices, and from referring to racial issues during job trainings.

“This Court is once again asked to pull Florida back from the upside down,” wrote U.S. District Judge Mark Walker, an Obama appointee.

In 2018, the couple had felt a modicum of optimism after Ms. Payne spearheaded an effort in Alachua County to gather petitions to put a voting rights referendum on the ballot that year.

The referendum restored voting rights to those who have served a sentence for a felony. Not only did it make the ballot, but it was also approved by 64% of Florida voters.

“We talked to a lot of people who wore MAGA hats, who identified as Republicans,” says Dr. Ortiz.

“We didn’t convince everyone, but their thing was, ‘Look, these people, if they’ve done their time, they’ve paid their penalties to society; they should get their voting rights back.’ We could not have won that struggle and got it on the ballot unless we actually attracted a lot of Trump and DeSantis supporters,” he says.

As a Florida historian, he spent most of his career teaching students about Florida freedom struggles. His award-winning book “Emancipation Betrayed” explores the history of the struggles of Black people trying to find freedom in Florida.

Dr. Ortiz also studies the descendants of Black freedom fighters who fought in the Seminole Wars during the administration of President Andrew Jackson.

“Those struggles for freedom,” he says, “are exactly what Ron DeSantis and the state of Florida don’t want you to know about. They want you to believe that the U.S. was created equal, perfectly.

“But the idea that African American slaves would come to Florida and have to fight the U.S. government in the Second Seminole War – that was the second-most expensive U.S. war, per capita, and it was a war for freedom against the United States of America – [this shows] there has been a continuity in terms of Black and Native freedom struggles here,” Dr. Ortiz says.

But the pressure of living in a state becoming more and more hostile to such ideas – it was crushing his spirit. He had to leave.

“I’m not leaving just because of Florida,” Dr. Ortiz says. “I didn’t grow up in a perfect society. But I don’t remember librarians getting death threats. There’s something deeply wrong. It’s craziness.”

A conservative “utopia” that began with lockdown defiance

On the road connecting the dirt-poor farming communities of unincorporated Immokalee with the wealthy beach enclaves of Naples, Florida, there sits a 75,000-square-foot supermarket unlike any other.

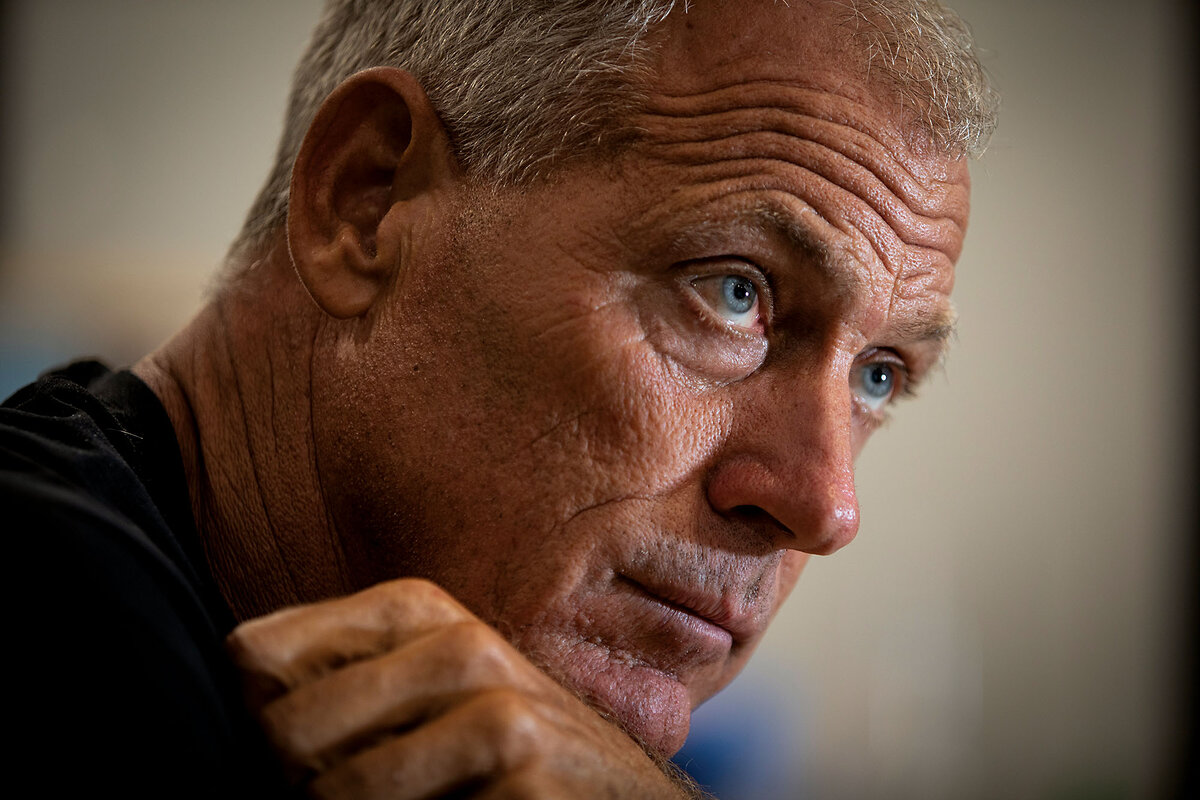

It’s called Seed to Table, and it’s the flagship store of Alfie Oakes, the entrepreneur and businessman in Collier County who owns and runs Oakes Farms, an operation that employs over 3,500 people and takes in around $25 million a year.

Mr. Oakes is also a controversial political firebrand and kingmaker in the Collier County chapter of the Florida GOP. And make no mistake, he is obsessed with freedom.

In many ways, he’s a classic conservative businessman, decrying burdensome government regulations and the morass of bureaucracies that stifle economic growth and innovation.

But this wariness of big government has morphed into something deeper. He views government and health officials, especially, as mostly a bunch of freedom-taking tyrants. This would include most of the establishment of university-trained professionals who populate most American institutions.

Mr. Oakes’ company is one of the largest independent agribusinesses in south Florida, consisting of more than 1,800 acres of farmland, numerous aquaponics and greenhouse facilities, and a fleet of over 100 trucks for its wholesale and retail operations.

But Seed to Table – which has sprawling spreads of produce, a food court with restaurants and kiosks, and a two-story wine market and tasting room – has become a MAGA mecca, many say, a shrine to former President Donald Trump and Trumpism.

The Florida entrepreneur launched Seed to Table in 2019 with fanfare. Then the pandemic struck, and Florida, like the rest of the country, ordered most residents to shelter in place, and the global shutdown began.

Everything about the government-ordered shutdown infuriated Mr. Oakes. His reaction? Defiance.

As an essential business with essential workers, Seed to Table didn’t have to be shut down. But Mr. Oakes openly flouted restrictions on large gatherings, making his supermarket in many ways a place to party. In fact, it became a pandemic destination.

“People were looking for freedom when they came here,” says Mr. Oakes, who currently serves Collier County as a state committeeman for the Republican Party of Florida. “They fell on their knees and cried. They came from lockdown cities and couldn’t believe what they saw. They didn’t think a place like this even existed.”

As a result of his defiance, he and fellow Republicans have dubbed Collier County “Freedom Town USA.”

Mr. Oakes’ story fits into classic patterns of American mythology and ideas of self-won freedom. In the 1970s, his father, Francis Oakes Jr., fled to Florida, chased by creditors. He brought his family to a run-down part of Fort Myers, opening a small grocery market that struggled.

When the younger Mr. Oakes was a teenager, he decided to buy a truck and drive to Immokalee farms to buy tomatoes and watermelons in bulk. He sold them from the back of his truck on a road approaching the Cape Coral Bridge, which spans the Caloosahatchee River.

In 1986, when he was 18 years old, he opened his first market after leasing 40 acres of land to grow zucchini. He was brokering wholesale deals by the time he graduated from high school.

The elder Mr. Oakes’ legacy as a fierce champion of organic produce continues to impact his son. He calls his father’s efforts “a search for food freedom,” which he says goes to the core of health, awareness, and even identity.

Mr. Oakes is actually pretty crunchy for a conservative, if not necessarily a MAGA Republican. He’s proud to say he doesn’t use deodorant or sunscreen, saying they are potentially health-damaging.

He’s also building a clinic that will feature a newfangled hyperbaric oxygen chamber that simulates the pressure on the human body at 30,000 feet. This is said to increase oxygen to the body and help with health and longevity.

And while there have long been government restrictions on the sale of raw milk, Mr. Oakes believes raw milk is a cornerstone of health. After years of wrestling with health regulators, he bought his own small dairy farm that now supplies his store. The compromise with health officials is that his raw milk labels say, “Not for human consumption.” Most of his customers disregard what they see as the government’s wagging finger.

In February, he helped Collier County stop putting fluoride in its drinking water, which he believes is harmful.

“There’s an effort to shape a utopia here, and, honestly, I didn’t see it coming,” he says. “But so far, it’s working.”

But Mr. Oakes can be brash and aggressive in his political statements. He’s called George Floyd, who was murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis, a “disgraceful career criminal.” During the 2022 midterm elections, he warned that if Democrats “steal” another election, “I have enough guns to put in every single employee’s hands. I hope it never gets there.”

His inflammatory rhetoric has made his company lose business. He has had numerous contracts supplying food for the Department of Defense and other federal agencies, as well as some local school districts. A few of these have been canceled.

He says it’s the kind of targeted oppression that justifies some of Florida’s efforts to crack down on the ideas that fuel an oppressive Democratic-led society.

Desre Buirski sits outside Seed to Table, selling Trump paraphernalia. A self-described freedom fighter, she’s a conservative activist who agrees that sometimes freedom and authoritarianism are compatible. Efforts to restrict the ideas and actions of some can be done for the greater liberty of the tribe, she says.

The future is all that really matters. “We have a lot of patriots from all corners of the U.S. who live here,” Ms. Buirski says. “If you don’t look after freedom, you might lose it. And then you can’t get it back.”

Mr. Oakes sees it as a classic battle between two contrasting visions of freedom.

“Florida is a place where it’s individual freedom versus group freedom,” he says. “It’s the real question that divides us. Yes, we have common values. But we are evolving as Americans.”

“Collier County is the freest part of Florida, which makes it the freest place in the U.S.,” says Mr. Oakes. “I can’t think of anywhere else where I could be. It’s like we’re in freedom’s last corner.”