Sports in the US: Year-round madness

| Boston

After spending his entire life cheering for the Boston Red Sox, Bowdoin College sophomore Chris McCann was so over the moon when the team clinched a World Series spot in 2004 that he forgot an important French exam. Not to worry – his professor was a fan, too, and let him make it up later.

Jennie Chan, a 2009 Boston University graduate, thinks nothing of spending 85 percent of her income traveling to college games – even more, she admits, if you count all the T-shirts and trinkets she's purchased, not to mention the highway billboard touting her team loyalty.

By most accounts, Martha Coakley, the attorney general of Massachusetts, ran a rote campaign in her recent bid for the US Senate, which contributed to her loss to Republican Scott Brown. But in the three-deckers and sports bars around Boston, her defeat is traced to something else – the day she mistakenly identified Red Sox pitcher Curt Schilling as a Yankees fan.

How crazy are New Englanders when it comes to sports? How crazy are all of us, for that matter?

While Boston may be a bit manic about its pitchers and parquet flooring, more and more people throughout the United States are expressing a near-tribal affiliation to a particular sport, or, more particularly, to a sports team.

At a time when the economy is faltering, wars are raging, and the future seems worrisome on a good day, many are looking to sports as a source not merely of distraction, but of personal identification. It's gotten to the point where English may no longer be our official language. Sports might be.

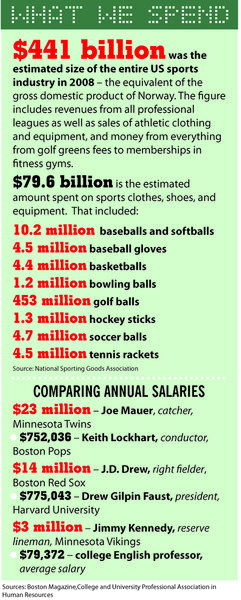

We listen to it endlessly on talk radio. We chat about it over the cubicles at work. We push our kids into it when they are still in their Maclaren strollers. We spend vast amounts of money on everything from LeBron James jerseys to greens fees: The National Sporting Goods Association estimates that sports represents a $441 billion industry in the US – the same as the gross domestic product of Norway.

Nor are Americans alone in their passion. Consider any soccer match in Europe. Or the priest in Vancouver, British Columbia, who was asked if he would skip a Sunday mass that threatened to conflict with the US-Canada Olympic hockey face-off. No, said the priest – but he would wrap it up in 15 minutes.

All this is hardly a bad thing. Sports, after all, teaches us about discipline and how to play with others. It gives us a diversion from the mundane aspects of human existence. It makes us less sedate and more communal.

"In a world where most people can't agree on anything, people can agree on a passionate interest in sports," says John Skipper, executive vice president of content at ESPN, the sports network.

Even more broadly, it is one of the few phenomena that can transcend race and class divisions, becoming what Bill Littlefield, who hosts a sports show on National Public Radio, calls a "marvelously easy social lubricant." "It's much easier to talk about that than subjects that require actual knowledge, such as the economy or healthcare packages or whether or not we should be invading more countries," he says. "It's sort of ... a feeling of belonging that is easy to get, easy to achieve."

Sports, in another words, may be the closest thing Americans have to a national hearth. "Sports is one of the most overt and direct expressions of community identity that we have in our society," says Andrew Zimbalist, a sports economist at Smith College in Northampton, Mass.

But has our love affair with sports gone too far? Something certainly is out of whack in a culture when marriages can crumble over obsessive sports worship; when friendships fracture over a clipping call; when hours of productivity are lost to sitting in front of a TV or computer screen, watching games, reading jock blogs, or lingering over online sports sites.

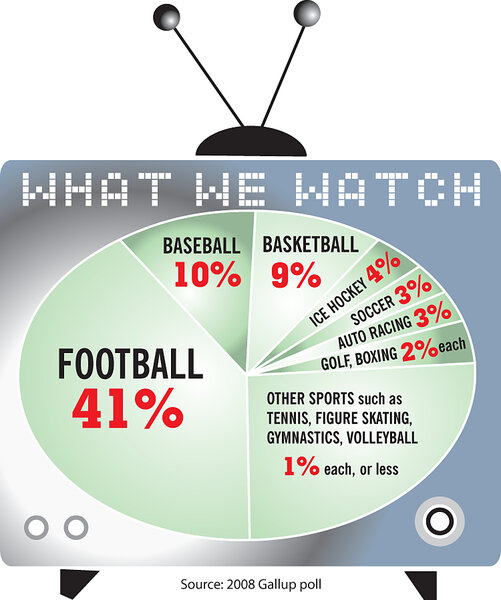

Last fall, an average 19.4 million armchair quarterbacks settled in weekly to watch NFL "Sunday Night Football." An estimated 58.3 million Americans will fill out a NCAA Tournament bracket this year, including our hoopster president, Barack Obama.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines fanatic – from the Latin fanaticus – as frenzied, marked by excessive enthusiasm and often intense, uncritical devotion. Another definition might be when too many people want their kids to become a third baseman instead of a molecular biologist, when a society talks about Tiger Woods's return to the Masters more than the Afghan war, when the NFL draft creates as much buzz as draft legislation on financial reform (who, honestly, had even heard of Mel Kiper Jr. just a few years ago?).

In short: Just how sports-obsessed have we become?

It's the economy, sports fans

When America went through its last calamitous economic decline, in the 1930s, baseball and week-long dance marathons helped provide some diversion. With the current economy in the worst shape since the Great Depression, distraction is once again in order.

Ms. Chan is in need of distraction. She has lived with her parents in Washington, D.C., since leaving college. She has applied for 131 jobs in the past year, but has yet to receive an offer better than the one from the Maryland J. Crew store where she works part time.

What little money she does make all goes to one goal: attending as many Duke University men's basketball games as possible in the year before she heads to law school. While she may be broke, she doesn't regret a single cent that she has spent.

"To me, the most astonishing and amazing thing is that despite how bad the economy and job market is, students and fans come out to these games to cheer on their beloved teams," Chan says. "For those 40 minutes, everyone is fixated on the sport, maybe as a distraction from all the outside negativity, or maybe it is all the excitement that the team brings."

What she represents is a variant of the "lipstick effect," the spending phenomenon after 9/11, and it's one reason stadiums continue to draw crowds despite a sullen economy. Following the terrorist attacks, consumers cut back on purchases of luxury goods but increased spending on smaller indulgences. They bought fewer designer shoes, for instance, but stocked up on expensive lipstick. Now, according to Richard Johnson, curator of the Sports Museum, an educational institution in Boston, people are cutting back on exotic vacations and instead taking more "staycations" – including trips to the local ballpark and hockey arena.

Even these relatively cheap alternatives for family getaways are still costly, though: The Team Marketing Report, a sports research firm, found that the average cost for a family outing to a Major League Baseball game last season (which includes four tickets, parking, and the inevitable hot dogs and hats) was $196.89. In New England, the cost of being a fan is even higher: At Fenway Park, those accouterments totaled $326.45. The only place more expensive to catch a game is the new $1.3 billion Yankee Stadium, where family fun consumed $410.88.

"If you're going to spend your money somewhere to be entertained, chances are you're more apt to sit in a ballpark for a game than to take a flight to Cancún," Mr. Johnson says.

That rationale probably extends to other "necessities" as well. "I'm sure the sports TV cable package is the last thing that's being canceled by somebody that's unemployed," Johnson adds. "You would probably be maintaining your health insurance, maybe your car payment, but you're certainly not going to lose your sports package on cable."

Officially, the US recession started in December 2007. It's true that attendance at pro sports games, except for National Hockey League games, has gone down since then, but only by a negligible amount. In 2007, an average of 67,755 people turned out for each National Football League game. In 2009, the league's per-game attendance was 67,509, just a 0.4 percent drop. "In terms of the fans, they need their distractions, so sports are a little more insulated [during recessions] than other industries," says Mr. Zimbalist.

Even if we're not physically at the ballpark, the mental space fandom takes up can ease stress on the wallet. Peter Geller, director of fantasy sports products at Yahoo, says that more than 10 million people play fantasy sports online every year. The time people spend checking scores and updating rosters represents a form of free entertainment. "It's a cheap way to have fun and to occupy your time, instead of spending money at the mall," he says.

Culture of the cubicle

$1.8 billion. That's how much outplacement firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas, Inc., which conducts an annual study on workplace productivity (or lack thereof) during college basketball's March Madness, says employers will pay in wages to unproductive employees between "selection Sunday" (March 14) and the end of the first round (March 19). The firm estimated that during the first week, workers would spend at least 20 minutes a day talking about the tournament, watching games online, or fiddling with their brackets.

(And there's an endless amount of fiddling to be done: If you created a unique March Madness bracket every second, it would take 30 billion years before you ran out of new combinations.) A Microsoft/MSN poll last year found that 45 percent of people planned to participate in at least one office pool during the tournament, so those 20 minutes per person add up to billions of dollars.

The guilty pleasure of watching sports at the office is widespread. CBS Sports began streaming all the college basketball playoff games on-demand in 2008, garnering 4.92 million viewers in the first year and raising its viewership 75 percent last year, tempting 7.52 million people away from their work to watch. And, yes, we know for a fact they were at work: Nielsen's Web ratings show that 92 percent of the site's traffic came from work computers.

Even better: CBS provides a "Boss Button" with its video player. In case of a boss-related emergency (meeting, cubicle check-in), the worker can click on the Boss Button and a spreadsheet will fill the screen, shielding the video from prying managers. The Boss Button's no joke, either: Nervous cubicle lurkers clicked it 2.77 million times during last year's tourney.

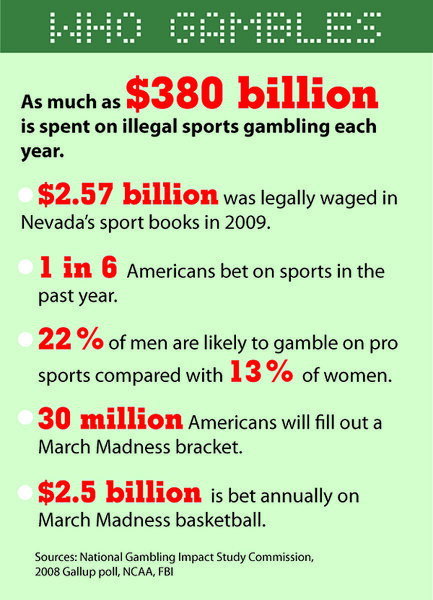

The impact of March Madness can be more nefarious than just idle workers. The FBI estimates $2.5 billion is bet annually on the month-long tournament. Experts believe even simple wagers can lead to more dangerous forms of betting. "You always start somewhere, and for sports gamblers, it's NCAA brackets or Super Bowl squares," says Timothy Otteman, a sports gambling expert at Central Michigan University in Mount Pleasant.

Others, however, see beneficial effects from the water-cooler chats and friendly intra-office pools. They believe talk about the previous night's games may do more to promote office bonding than expensive company-sponsored retreats. "I think people who have fun at work ultimately end up being more productive," says Mr. Skipper of ESPN. "Camaraderie at work only builds team spirit."

Plus, many have pointed out, in response to the Challenger, Gray & Christmas report, that the lines between work life and home life have blurred. With the advent of smart phones and mobile Web capabilities, people can work anytime, anywhere, including while sitting in a recliner in front of a television, watching their favorite team. Inversely, many office workers use company time to shop online, make personal calls, and peruse social-networking sites – and that happens all year, not just in March.

My dinner with Andre (Agassi)

The typical modern American family does not eat dinner seated perfectly around an oaken table like a 1950s sitcom brood. They usually are not talking about who did what in school, or how the day went at Dad-and-Mom's workplaces, or about the merits of China floating the yuan. No, they are often watching television. Sports television.

Maybe it's one of ESPN's seven 24-hour channels, or any of the multitude of specialty networks: New England Sports Network, MLB Extra Innings, Fox Sports, MLS Direct Kick, the list goes on like a Dick Vitale commentary. And what they are eating most likely came from a box that one of the parents picked up in a rush on the way back from Sarah's soccer game, Teddy's lacrosse practice, Joey's pitching lessons, or Mary's basketball tryouts. Sports and family: The new American equation. The family that plays together... well, this family is only sort of staying together.

Teddy and Joey are on their computers, reading about their favorite teams; Sarah is texting her friend about a soccer game; Mary is on her iPhone, talking about basketball hairstyles. Dad is playing fantasy baseball and Mom is wondering if, just once, everyone might congregate at the table.

But when sports aren't co-opting the dinner conversation or dividing rival fans, a shared enthusiasm for what happens on the gridiron or diamond can be a unifying force. "At the end of the day, that's what makes sport so compelling, it's the great common denominator," says Peter Roby, athletic director at Northeastern University in Boston. "Sport can be such a link. It can bring people from such diverse backgrounds, politically, religiously, socioeconomically, ethnically."

Technology has expanded the unifying potential of sports. Fans have always tailgated or painted their faces in bizarre ways to show team loyalty. But now, as cameras broadcast fans flashing their team colors out into the electronic ether, devotees everywhere can identify with their partners in passion. Suddenly, an isolated clique becomes a global fraternity. "It's just how they are able to articulate their passion now to the rest of the world that's totally different," Mr. Roby says.

Mr. Geller, the fantasy sports guru, typifies how technology is creating bonds. He's participates in a fantasy NASCAR league with his 7-year-old son. "It's purely for fun," he says. "I don't really care who wins. I just love the fact that we get to spend the 15 or 20 minutes a week together discussing it and getting online together and picking our drivers."

Sports have also helped Sam Butterfield, a student at Hampshire College in Amherst, Mass., tighten ties with his family, particularly his father and older brother, both avid sports enthusiasts. "It's a theology all of itself," he says. "It's both a ritual and a catharsis. It allows people who might differ in terms of personality and temperament to pull for one collective set of values."

The kid in all of us

Nowhere is our cultural zeal for sports better reflected than in youth athletics. The "stage moms" of old are now sideline moms and coaches, shepherding little Timmy or Sue to practice every day. More than 60 million kids play youth sports, up from 52 million in 2000 and 46 million in 1997.

But these ballooning statistics raise the question: Are Timmy and Sue being pushed too hard to fill a void in their parents' lives or is playing beneficial to them?

Steve Barr of Little League International, says his and other youth sports groups are there for the children, not the parents. Every child plays in every game, regardless of skill or parental demands. "We have to make sure it doesn't get to the point where it's not a game anymore...," he says.

To do that, experts say, it's important that kids actually participate in sports instead of just viewing them on TV or a computer screen. "I think there's no substitute for participation, no substitute for feeling included and getting an identity," says Dan Lebowitz, head of the Center for Study of Sport in Society at Northeastern University in Boston. "Sport at youth levels, middle school levels, high school levels is a space for healthy development, for conflict resolution, for healthy competitive spirit, for cooperation, for all those things that it should be."

Still, the positive experience that kids get from playing sports can be muffled by an overzealous parent. "There are certain individuals, like the parent of an adolescent or a youth athlete, who can get so overinvolved that it can take the fun out of the game for the child...," says Tom Newmark, president of the International Society of Sports Psychiatrists. "Youth sports should be fun."

Sports deities: How much worship?

Whether you bow at the altar of Boston's Fenway Park or think Pesky's Pole is something that props up power lines, one thing is certain: Sports are here to stay.

Since the era of the Roman gladiators, fans have lined up to see athletes perform. Today, whether it's David Ortiz ripping a pitch into the gap, Tyson Gay running 100 meters in less than 10 seconds, or Serena Williams sizzling an ace past her opponent, people crave seeing their athletic idols perform seemingly superhuman feats.

Zimbalist says that sports are "a manifestation of the ability of humans to transcend or come close to transcending the human limitations and boundaries of human excellence and importance." "Just like the Greeks had demigods who performed magical acts and had powers and were able to transcend their mortality, athletes do that," he says.

Johnson calls sports "the ultimate reality experience." Fans are voyeuristic, living and dying with teams' successes or failures, taking players' performances personally. "They're wearing a uniform with the name of your hometown or where you come from, so you have a connection to that," he says.

Well, maybe. Some sports aficionados caution that players switch teams so often today that we don't – or can't – develop real loyalties. "I mean, how many teams did Curt Shilling pitch for before he wound up pitching in Fenway Park?" asks Mr. Littlefield, the radio host. "In a way, a friend of mine says, we root for the laundry – whoever happens to be employed and wearing a Red Sox jersey, we root for them."

Johnson argues that player loyalty doesn't matter – it's the devotion to the sport and its heroes that make the fan experience irresistible. "Not everybody has gotten on a stage and given a speech or performed in a play, but just about everybody tried out for a Little League team or ran a race or threw a football," he says. "We can connect to the activities these people are engaged in on a spiritual or visceral level."

But the question is, when does the visceral become a vice? David Barash, a psychology professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, says Americans obsess over sports the same way they do over reality TV shows. He says when a local team wins, people think "we" won. He says that's an illusion. It's not "we." It's "they" – the team – that won. People would be far better off, he argues, if they would spend less time and money on tickets and cable TV packages and more on experiencing life for themselves.

"They should go out and participate in sports, they should go for a walk, listen to music, talk to their kids, play with the dog ... anything that's real," he says.

More broadly, some critics argue our überemphasis on sports shows a skewed set of priorities. Murray Sperber, a visiting professor at the University of California, Berkeley, Graduate School of Education, notes that many public universities pay football coaches far more than school presidents.

John Gerdy echoes that point. "LeBron James is much more important and valued by society than some Nobel Prize winner or someone on the brink of a major discovery in cancer research," says the professor of sports administration at Ohio University in Athens. "And there are consequences for that, because we are telling our children that this is what we value."

Still, there might be a middle ground in all of this. Mark Beudert, director of opera studies at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, has three arts-obsessed children. The key, he says, isn't valuing a cellist over a shortstop. It's striving for excellence in anything we do.

"There has to be a view that people in both sports and the arts – in any area of achievement – have the same motivation to excel and interface with society in a certain way," he says. "The motivation is the same if you're playing football or playing the violin; the individual just chooses a different way to express that motivation."

Chris McCann's French professor would probably agree. So might Jennie Chan. And most likely Martha Coakley now knows that Curt Schilling is not a Yankees fan.

• Kase Wickman, Scott McLaughlin, and Tom Lakin are Boston University journalism students. This article was written for a class taught by Prof. Elizabeth Mehren.