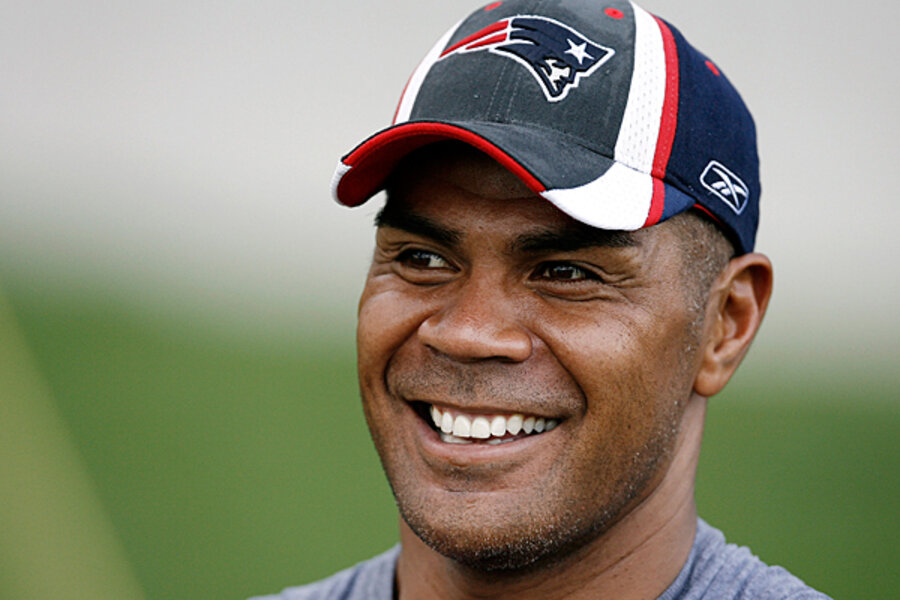

Junior Seau tragedy shakes NFL, intensifies concern about head injuries

Loading...

Junior Seau’s death from an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound has shaken the NFL to its core, sending to fever pitch the ever-louder debate about player safety and the long-term ill effects of playing pro football.

The timing is hard to ignore. The shocking news of the former linebacker's apparent suicide broke Wednesday just hours after NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell issued harsh suspensions to four NFL defenders for their roles in the New Orleans Saints bounty scandal, in which defenders were paid for dealing game-ending hits to opposing players. Reggie Bush was among the players who took to Twitter to denounce the severity of the suspensions and to lambast Goodell for trying to turn football into a wimpier sport, and then to mourn Seau a few minutes later.

According to some, the culture of toughness that led to the Saints’ punishments (and the player backlash) may have been Seau’s undoing.

His death is the latest of several NFL veteran suicides in recent years. In February 2011, ex-defensive back Dave Duerson shot himself in the chest, leaving a note requesting that his brain be donated to the Boston University School of Medicine for research. Those who conducted the examinations said head injuries he had sustained during his time in the NFL resulted in significant, long-term brain damage. Just last month, retired safety Ray Easterling committed suicide, amid reports that he had experienced depression, insomnia, and memory loss toward the end of his life. Easterling was a lead plaintiff in a lawsuit filed by a large group of former players against the NFL for failing to protect them from head injuries. Nearly 1,000 ex-NFL players have been named as plaintiffs in such suits against the league.

Seau’s end, though, hits the NFL especially hard, according to Mike Tanier, staff writer of Football Outsiders. A definite future Hall of Famer, Seau was one of the best defenders ever to play the game, and he capped off his two-decade playing career very recently, in 2009.

“This one is going to be more real to recent players,” Mr. Tanier says. “I hope this reaffirms that the tough-guy rhetoric needs to be gone. This is about something dangerous. These things should change the culture, and the conduct on the field.”

During his playing days, Seau was never sidelined for a head injury. But family and friends have stated that he sustained multiple concussions during his career. "Of course he had,” ex-wife Gina Seau told ESPN. “He always bounced back and kept on playing, He's a warrior. That didn't stop him. I don't know what football player hasn't. It's not ballet. It's part of the game."

According to Tanier, it’s a part of the game that was all but ignored until recently. “The change in the concussion mentality occurred in the last few years, across sports,” he says. “[Seau’s] glory days were 1992 to 2000. A player in the '90s who took time off for concussions was going to get criticism from teammates, coaches, owners, fans, talk radio.”

Moreover, men whose careers had depended on their physical and mental toughness are generally unlikely to seek help or to let on that anything might be wrong. Seau, for instance, was seen smiling at a charity event days before his death.

This is true of retired players, regardless of injuries, says Dale Jasinski, professor of management and director of the Professional Athlete Transition Institute at Quinnipiac University in Hamden, Conn.

“It’s a lot like the military,” Professor Jasinski says. “Of course, I’m not saying that being shot at in Kandahar is at all the same as being tackled on the 30-yard line.” But, he argues, the parallels are there. “In both cases, you’d be shocked at how little the degrees of freedom are. It’s a very structured existence.” One retired player whom Jasinsky worked with described a football career as standing in a series of hallways, being constantly told which room to go to. That structure comes with a huge support system of coaches and caregivers, which disappears after a player retires.

What’s more, “your physicality is your livelihood, and you have lived in an environment where weakness is not a career-building move,” he says. “That continues after retirement. There’s always the challenge of piercing through the persona of what they believe they should be like.”

Such is the challenge for the NFL in making the game less dangerous and reaching out to veterans – shifts that Tanier says must come from the top.

“I would like the league to take more of a whole-patient approach to veterans. The physical health care they need, counseling services, networking services, maybe a hot-line situation. These are the kind of guys who are not going to run to a psychologist.... [They need] something to ease that transition [out of the pro football world]."

Regarding the problem of head injuries, “the league is getting a good start at addressing it,” he says. “It’s impossible to go zero tolerance on concussions, but you can go zero tolerance on unsafe behavior. The league is taking this seriously. There’s no mixed message in the [Saints'] bounty punishments, and everything seeps down to college, prep, and Pop Warner levels.”

He notes the last time the NFL took action against unsafe conditions for players, when Minnesota Vikings offensive tackle Korey Stringer died during a 2001 training camp from what doctors said was a heat stroke. That led the NFL to institute major changes to prevent dehydration, including ensuring that shade and fluids were readily available at practice sites, and to increase scrutiny on pressuring players to “bulk up” to unhealthy weights.

“If NFL players are getting a water break every 45 minutes, then you don’t have high school coaches in west Texas holding six-hour practices and then allowing water breaks only after they’re done,” Tanier says.

But he warns that the changes Comissioner Goodell is pushing to curtail head injuries may not bear fruit for years. "I’m hoping these penalties [like those meted out to the Saints players] will stop something like this [Seau's death] from happening 15 years from now. In the Twitter cycle, we want the switch to be flipped immediately, but the switch can’t get flipped immediately. This is going to take time.”