World Cup: Is America a real soccer nation? Increasingly, yes.

| Portland, Ore.

The line stretches down the long block and around the corner. People are sitting in camp chairs and huddled near makeshift tents, some calling out chants with their neighbors, their breath visible as the thin spring light fades into dusk.

This isn’t the line for the release of the next iPhone. People are waiting outside Providence Park in Portland for a soccer game. And kickoff time? It’s more than 24 hours away.

Welcome to what locals call Soccer City, USA. Nearly 21,000 people have packed the sold-out stadium in every game since the team’s inaugural season in Major League Soccer (MLS) in 2011, win or lose, rain or shine. From the national anthem to the final whistle, noise floods like an audible tide from the Timbers Army supporters club in anticipation of Timber Joey cutting off a slice of a log with a chain saw every time the home team scores a goal.

For a sport that is still seen as foreign or fringe across broad swaths of the United States, the scene looks distinctly American and genuinely passionate. It is a glimpse of the soccer nation that America is slowly becoming.

Twenty years ago, when the World Cup first came to the US, it found a nation that mostly thought of soccer as Saturday-morning exercise for grade-schoolers. But even then, the question loomed: What will happen when all these kids grow up? Will they be – gulp – soccer fans?

Now, as the US team prepares to play its first game June 16 in the 2014 World Cup in Brazil, the answer is that soccer has a ways to go before it becomes as big as football, baseball, basketball, or even hockey. But thanks in part to many of those kids, it is no longer a punch line.

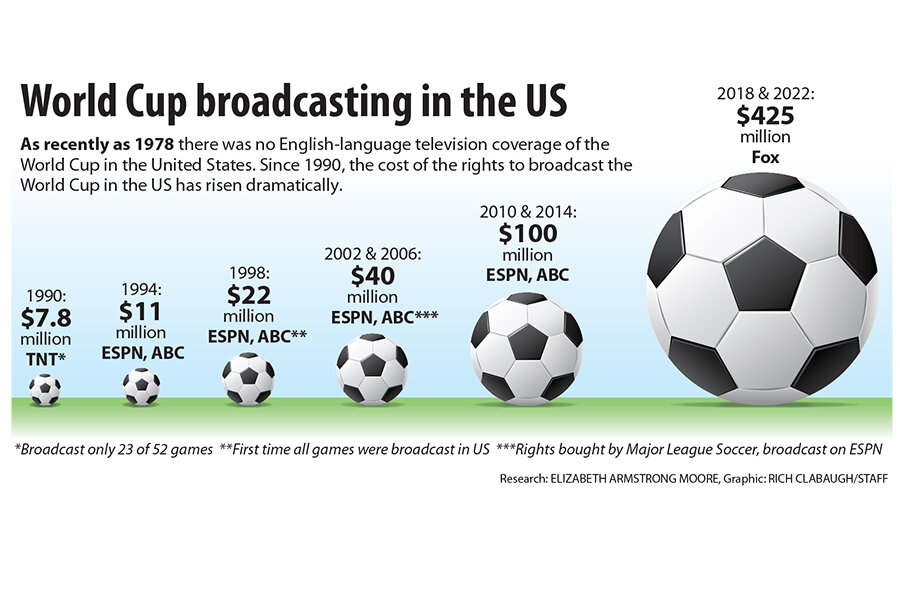

No country paid more for the rights to show the 2018 and 2022 World Cups than America, with Fox forking over $425 million after a bidding war with ESPN. In 2011, average attendance at MLS games was 17,872 – higher than at National Basketball Association games or National Hockey League games. And in 2013, the New York Yankees and English Premier League-champion Manchester City Football Club jointly paid $100 million to form the New York City Football Club (FC) and join MLS. David Beckham has been cleared to own a new team in Miami, too.

Unlike 20 years ago, soccer in America is now big business, and the trend line is up.

“It’s all going in an upward direction,” says Andrew Zimbalist, a sports economist at Smith College in Northampton, Mass. “People are expecting a eureka moment where all of a sudden it’s as popular as baseball, but if you project out 20 or 30 years it’s a reasonable bet that soccer will be ascendant all this time and it will surpass even football.”

Portland as Soccer City, USA

In other words, to see the potential future of soccer in America, take a look at Portland.

“We used to say that this atmosphere is as much like Europe as anything you’ve seen, but that doesn’t do it justice because it’s uniquely American and it’s uniquely Portland,” says Merritt Paulson, owner of both the Portland Timbers and the city’s two-year-old pro women’s team, the Portland Thorns, who draw an average of 14,000 fans a game – several times as large as any crowd for any women’s soccer team anywhere in the world. The Timbers have sold out 50-plus consecutive games and the season ticket waiting list is roughly 10,000 names long.

How did Portland do it? Perhaps it all started with Timber Jim.

Back in 1975, when a previous incarnation of the Timbers played in the long-defunct North American Soccer League (NASL), Jim Serrill wanted to get the fans a bit rowdy. Being a muscled slab of a man who worked in the tree-trimming trade, the bearded Mr. Serrill proposed bringing his chain saw to games. The club politely declined, then, curiously, counteroffered. Would Serrill be so kind as to cut a slice of wood off a large log in front of the stands every time the home team scored a goal? Serrill happily obliged, and Timber Jim was born.

Timber Jim was there through the NASL days, and through the days when another incarnation of the Timbers toiled through the unglamorous American minor leagues. And somehow, over the years, he became something more than a big dude with a chain saw. He became Portland.

This is the story of soccer in Portland. The Timbers are not three years old. They are 30 years old, and over those decades the fabric of the team began to be interwoven with the city. In soccer, the most tribal of sports, long passages of goalless play become the stage for fans themselves to become the attraction with songs, chants, and game-day traditions. Soccer is not a spectator sport; it is a participatory and intensely social event. And Portland came to embrace that as a part of its civic identity.

In 2004, when Timber Jim’s daughter, Hannah, died in a car accident, he broke down while trying to lead the crowd in song. It was “You Are My Sunshine,” and as he faltered, the crowd sang it for him – and to him. They still do. The Timbers Army sings “You Are My Sunshine” near the 80th minute of every home game.

“My eyes well up just thinking about what has happened surrounding this crazy game,” says Serrill, who passed the torch to the younger Timber Joey in 2008. “If you sing the whole 90 minutes, and you’re standing, you’re emotionally involved and invested, and it’s a better experience.... I’ve never been to any other type of event where people are that crazy. They let it all out.”

What Mr. Paulson, the owner, has been able to do, is market that tribal identity to the city’s 20- and 30-something hipsters – making the team a statement of the city’s counterculture “Keep Portland weird” identity. Giant billboards downtown bear the hashtag #RCTID after the Army’s “Rose City ’Til I Die” chant. (In the interest of full disclosure, Paulson is related to a Monitor staff member.)

“When it comes to off-the-field work, the Timbers are the standard that other MLS teams look up to,” says Mike Donovan, a Portland-based reporter for the soccer news site Soccer By Ives. “I cannot overstate how important that has been in the emergence of the modern-day Soccer City, USA.”

The Kansas City experiment

The same is true in Seattle, where the Sounders have filled the void left by the loss of the NBA’s Sonics to Oklahoma City in 2008. Every game day, fans gather in Occidental Park to march to the stadium, led by a 53-member marching band. Average attendance is over 40,000.

Meanwhile, other cities have shown that Cascadia can be replicated elsewhere. When MLS started in 1996, the Kansas City Wiz played in a cavernous football stadium and were routinely at the bottom of the league in attendance. In 2010, new ownership built an intimate soccer-specific stadium and changed the team’s name to something more traditional, Sporting Kansas City, as part of a broader effort to sell the team to core soccer fans. The changes have been transformative.

“Yes, Portland and Seattle are outliers, but I think there’s a strata of teams right underneath them that are doing very well,” says Jeff Carlisle of ESPNFC.com, a soccer website. “I keep thinking back to Kansas City. That franchise was dead, going nowhere fast, and the new owners came in and said, ‘Hey, we’re gonna build this new stadium.’ And I just remember thinking, ‘Who’s going to turn up?’ And they nailed it. The building has to come first, this intimate, close-to-the-field, almost hemmed-in type of venue that creates intensity.”

Mr. Donovan of Soccer By Ives predicts that “in 10 or 20 years, there will be a lot more cities with rabid fan bases,” because even for cities without the traditions of Portland, soccer has “exploded” in the past few years.

The evidence is compelling.

Soccer in America by the numbers

In March, for the first time in the 20-year history of the ESPN Sports Poll, Major League Soccer caught up with Major League Baseball as being equally popular (at 18 percent) among 12-to-17-year-olds. In 2012, the poll found that among 12-to-24-year-olds, soccer was ranked America’s second most popular sport after football – ahead of not just baseball but basketball, college football, and hockey.

Meanwhile, the youth-soccer trend continues. According to the National Federation of State High School Associations, participation in all major group sports has dropped or stayed flat since 2008 with one exception: soccer. Youth participation shouldn’t be discounted because it translates to more adults down the road fluent enough in soccer to seek it out on TV, says Professor Zimbalist.

“The thought that it’s a foreign sport in any way, shape, or form is not true,” says Sunil Gulati, president of the United States Soccer Federation.

Now, there are the first inklings of big money in the sport. When MLS launched in 1996, it was propped up by a handful of investors who, in some cases, owned more than one team because no one else wanted to buy in. Meanwhile, the MLS television contract was essentially an infomercial, with MLS having to buy time. The top player salary was listed at $270,000.

Contrast that with today. The Yankee-owned New York City FC is ready to start play next year, with Mr. Beckham’s still-unnamed Miami club to join soon after. MLS has a $70 million national TV deal. And Clint Dempsey of the Seattle Sounders makes roughly $8 million a year.

Surely, Beckham helped bring exposure and credibility to the league during his five-year stint with the Los Angeles Galaxy from 2007 to 2012. But soccer’s foundations are sunk much deeper – in the 12 soccer-specific stadiums built since 1999, with at least four more on the way.

“The Pacific Northwest is the epicenter in terms of authentic atmosphere,” says Paulson. “But it’s a much bigger story than that.... It’s one of the most staggering growth stories for any major sports property in recent history, the MLS story.”

Still, he says the league has its work cut out for itself because it is the only major American sports league that is not the best in the world.

“The fact of the matter is this is a soccer nation, but a lot of those people are watching the English Premier League and not Major League Soccer,” Paulson says. “So MLS has to get better on the field and pull a lot of those people because we can offer something they can’t, which is the ability to support your team in person and enjoy a live game. Because Americans are used to supporting the best leagues in the world.”