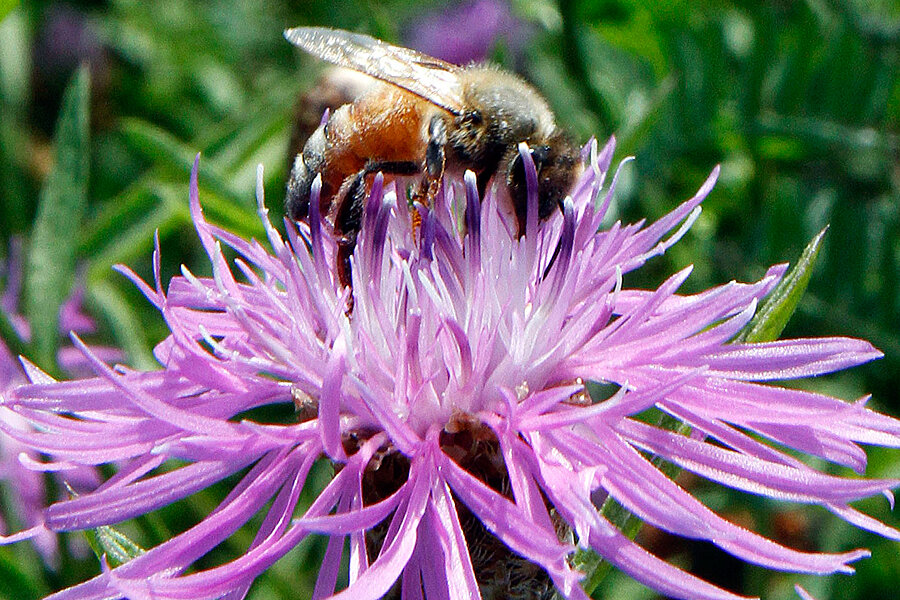

Not just honeybees: Affliction may be spreading to bumblebees, scientists say

The mysterious disorder that has befallen domestic honeybees may be spreading to bumblebees, researchers say.

Beekeepers in the United States and Europe have documented massive honeybee losses for several years, but less has been understood about their wild counterpart, the bumblebee, which also appears to be in global decline.

American beekeepers first reported the mysterious death and disappearance of entire colonies of domesticated honeybees in 2006. Since then, apiarists have implicated multiple culprits working in concert, including pesticides, viruses, and exotic pests. It now appears that the same pathogens and pests that have befallen honeybees may also be affecting wild pollinators as well, according to a paper published online by the scientific journal Nature Wednesday.

“Ongoing spillover of EIDs [emerging infectious diseases] could represent a major cause of mortality of wild pollinators wherever managed bees are maintained,” the study authors write.

While the researchers cannot say with certainty which direction the pests and pathogens are traveling, from honeybee to bumblebee or vice versa, they say that the higher percentage of infection in honeybees suggests that honeybees are the primary hosts.

Honeybees in the US are actually European honeybees (Apis mellifera) and are not native to America.

A survey of 26 sites in Britain found that 20 percent of bumblebees suffer from a virus that has been identified in 88 percent of honeybees, the researchers report. The researchers also found evidence of the fungal parasite that afflicts honeybees in British bumblebees.

“Although our data are only drawn from Great Britain, the prerequisites for honeybees to be a source or reservoir for these EIDs – high colony densities and high parasite loads – are present at a global scale,” the paper states.

American researchers have also seen evidence of this spillover effect in the US.

In the US, there are 20 species of bumblebees, four of which are considered endangered, says native bee expert Cory Stanley-Stahr of the University of Florida in Gainesville. While habitat fragmentation plays a major role in the decline of American bumblebees, there is also evidence that pathogens are contributing to bumblebee losses as well, she says.

Researchers at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, examined data collected between 2009 and 2010 from 30 honeybee colonies and local native bumblebee populations across seven states and found preliminary evidence that pests and pathogens may be spilling over from managed colonies to native bees.

Jason Graham, another native bee expert at the University of Florida, has been examining the potential spillover of pathogens between honeybees and the 300 species of bees (including bumblebees) found in Florida as part of his doctoral dissertation. He has found similar evidence that honeybees and bumblebees, as well as other species of solitary bees, share the same pathogens. He expects to publish his findings later this year.

While honeybees get much of the attention, the US is home to 4,000 species of native bees, which are equally important in the process of pollinating crops.

“In the United States alone, native bees contribute at least $3 billion a year to the farm economy,” Mace Vaughan, pollinator program director at the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation in Portland, Ore., told the National Wildlife Federation in July. “We grossly overlook the critical role these animals play.”

Certain plants, such as blueberries and sunflowers, can be pollinated only through buzz pollination, where bumblebees disconnect the muscle attaching their wing to their thorax and vibrate just their body, Mr. Graham says.