How scientists overlooked a 2,500-square-mile cloud of methane over the Southwest

Scientists have identified the largest hotspot of methane gas in the United States hovering over the Four Corners region of the Southwest, and the find could have big implications for how the country tracks its emissions in the future.

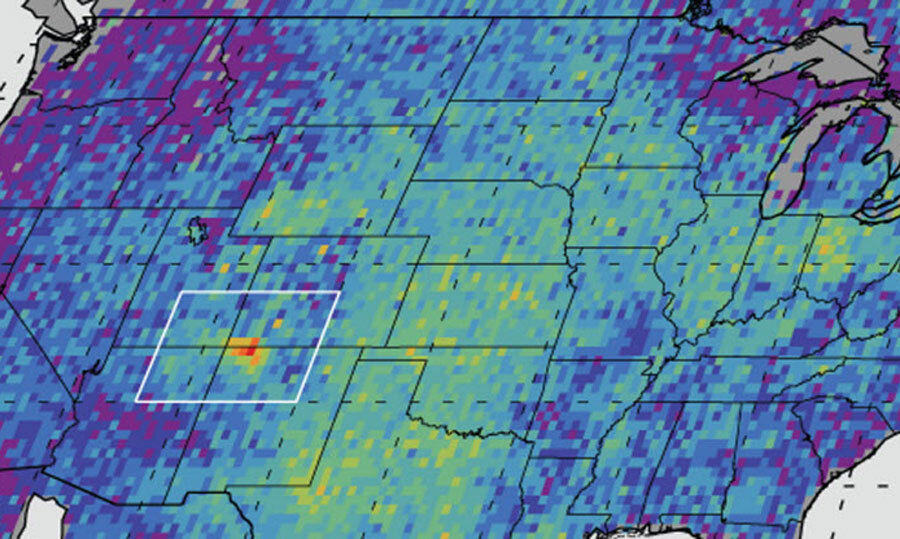

Scientists first noticed the data years ago amid satellite measurements collected by the European Space Agency's Scanning Imaging Absorption Spectrometer for Atmospheric Chartography (SCIAMACHY) instrument. The SCIAMACHY instrument collected atmospheric data over the US from 2002 to 2012. The bright red patch over the Four Corners persisted throughout the study period, but the readings were so extreme scientists still waited several more years before investigating the region in detail.

"We didn't focus on it because we weren't sure if it was a true signal or an instrument error," said Christian Frankenberg from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in a statement.

Frankenberg was co-author of a study released yesterday by the journal Geophysical Research Letters, which analyzed SCIAMACHY data from 2003 to 2009. The study used a year of ground-based measurements to validate the satellite data, and found that the region where Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah intersect had atmospheric methane concentrations equivalent to about 1.3 million pounds of emissions a year – roughly 80 percent higher than the Environmental Protection Agency estimates.

Methane is not as plentiful in the atmosphere as other climate-changing gases like carbon dioxide, but it is more than 80 percent more potent at trapping heat in the short term than CO2. The amount of methane believed to be hovering over the 2,500 square-mile area – about the size of Delaware – would trap more heat in the atmosphere than all the carbon dioxide produced yearly in Sweden.

The authors of yesterday's study are careful to note that the methane emissions they analyzed don't come from hydraulic fracturing in the region, a controversial method used to extract natural gas and oil that critics have blamed for releasing large amounts of methane into the atmosphere. Most of the measurements used pre-date the widespread use of fracking in the region.

Eric Kort, lead author of the study and assistant professor of atmospheric, oceanic and space sciences at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said that other industrial activity in the region is most likely the main culprit, in particular coal mining. The Four Corners sits on North America's most productive basin of coalbed methane, a type of methane that sticks to the surface of coal.

"While fracking has become a focal point in conversations about methane emissions, it certainly appears from this and other studies that in the US, fossil fuel extraction activities across the board likely emit higher than inventory estimates," Professor Kort says.

Since it's impossible to have instruments set up at every methane leak in the country, estimates are usually based on measurements from a few individual locations that are then extrapolated to reflect a rough estimate of emissions nationwide. A flaw with this system is that isolated, anomalous sources of methane, such as the Four Corners basin, can go unnoticed, Kort explains.

"We often see, as in this study we published, that there seems to be more methane in the atmosphere than is accounted for in the inventories," Kort says. "It’s a tremendous amount of work to compile and inventory like that, and its very valuable, but you’re only going to capture what you know to insert and you have to make these representative assumptions."

The high methane levels are not a health risk to people in the Four Corners, but scientists have been finding it difficult to accurately track and quantify the amount of methane being released into the atmosphere.

Methane inventories like those compiled by the EPA rely mostly on local measurements from towers and planes, and scientists believe those inventories reflect only half of US methane emissions. Estimates for the area in the European Union’s widely used Emission Database for Global Atmospheric Research were also 3.5 times smaller than what the study found.

Methane leaks naturally from gas formations around the world, and without a detailed historical baseline of emissions from a particular area it can be hard to determine how responsible industry is for methane emissions in certain areas, according to Terry Engelder, a professor of geosciences at Pennsylvania State University in State College.

"There is no baseline in the Four Corners region," Professor Engelder said in an e-mail. "Therefore, we really don't know to the extent to which the coal industry and coalbed methane increased and aggravated an existing, natural condition."

Engelder adds that the study on methane in the Four Corners will "further spur an effort to understand methane emissions in the US."

Satellite measurements could be an important tool for tracking greenhouse gas emissions in the future, Kort says, and could be especially useful at identifying, locating, and quantifying anomalous hotspots because "it's hard to hide" from satellites.

But there is only one satellite measuring atmospheric methane right now, according to Kort, and it measures methane in a different manner that makes the data more difficult to use.

"Right now NASA has no plans to launch a new methane satellite," Kort says, "and it may commit, or may not, [to a new satellite] based on other issues."