Why Michigan's new water plan is about more than Flint

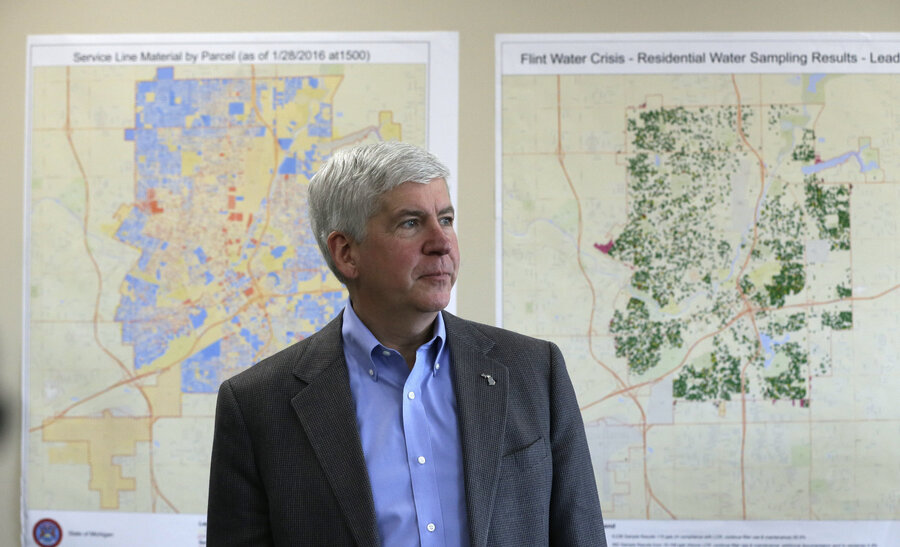

Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder and state environmental officials have released a 30-year plan to get Michigan’s freshwater protection back on track.

“There’s a framework here for long-term success,” Governor Snyder said Friday when announcing the plan to an audience on the shoreline of Lake St. Clair. “If there’s one thing that binds Michiganders together, as much or more than anything, it’s a love of the Great Lakes and the wonderful water resources we have in this state.”

The water of the Great Lakes State has been a topic of nationwide controversy for almost two years. In April 2014, city officials under a state-appointed water emergency manager decided to start using water from the Flint River to cut costs. Residents began complaining about the water’s taste and smell almost immediately, along with health effects such as rashes and hair loss, Jessica Mendoza reported for The Christian Science Monitor.

But it wasn’t until September 2015, after Virginia Tech engineering professor Marc Edwards studied the water, that residents learned their water supply had dangerously high levels of lead.

“Abundant freshwater resources are at the root of why many Michiganders choose to live, work and play in the peninsula state,” reads the report. “With 20 percent of the world’s available freshwater, four of the Great Lakes, more than 11,000 inland lakes, 76,000 miles of rivers, 6.5 million acres of wetlands and more than 3,200 miles of freshwater coastline – the longest in the world – ensuring the long-term sustainability of this treasured globally significant natural resource is critical to the integrity of the ecosystem, the well-being of nearly 10 million residents and our ability to advance Michigan’s prosperity.”

The state’s plan has five “key priorities”: ensuring safe drinking water, reducing phosphorus in the western Lake Erie basin by 40 percent, investing in commercial and recreational harbors, preventing invasive species from harming local ecosystems, and developing a water trails system.

And as this diverse to-do list suggests, Flint’s polluted drinking water is not the only water-related issue experienced by Michigan in recent years.

For example scientists and conservationists have been fighting back against 186 invasive species for years, an issue they refer to as “biological pollution.” These species enter the Great Lakes through canals or unlawful releases, and end up disrupting local food chains. They are estimated to have caused more than $200 million in damage annually by disrupting fishing and tourism economies.

For example the zebra mussel and quagga mussel are “causing the most profound ecological changes to the Great Lakes in recorded history,” says the National Wildlife Federation by disproportionately consuming the water’s phytoplankton – a popular food source for native fish. And after several sightings in nearby tributaries, Asian Carp remain a significant threat to the Great Lakes. If this invasive species takes hold, Asian Carp could become one-third of the Great Lakes’ total fish population, Lucy Schouten reported for the Monitor.

And while lead might be the first pollutant that comes to Americans’ minds when thinking about Michigan’s water, phosphorous pollution has been an ongoing struggle for years. Agricultural runoff, atmospheric deposition, wastewater, and stormwater have created phosporous pollution in the Great Lakes, which often leads to algae blooms, the US Environmental Protection Agency explains.

Along with being unappealing to beach goers, algae blooms can be dangerous. Two years ago, Toledo was without potable water for a few days after algae contaminated the city’s water source from Lake Erie.

So while the 30-year time frame may be discouraging to Michigan residents who want immediate action, meaningful improvements will take time. Because while safe drinking water in Flint is a top priority, Michigan has other freshwater issues to deal with.

As Eric Scorsone, an expert in city and state government finance issues at Michigan State University, told the Monitor in April: “I would say we’re moving in the right direction probably more slowly than people would like.”