Can Sanders supporters form a sustainable movement?

Loading...

Bernie Sanders has moved into a new phase of his presidential candidacy. He has both acknowledged that he does not have the delegates to receive the Democratic nomination ("we're good at arithmetic," he told CNN's Chris Cuomo) and that he will "in all likelihood" vote for presumptive nominee Hillary Clinton. Yet in more or less the same breath, he pledges to continue to campaign.

And his supporters appear happy to have him do just that.

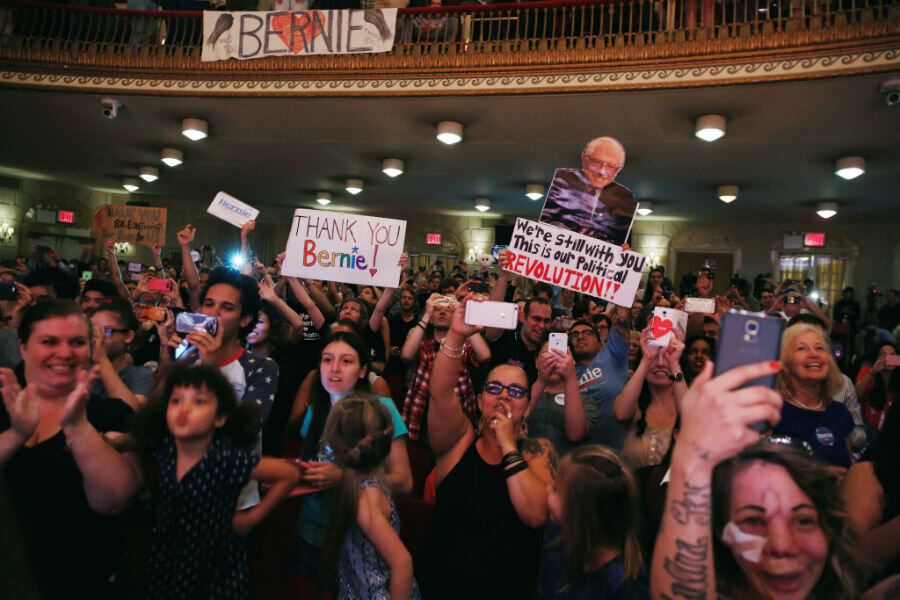

Yesterday, he stood before a crowd of roughly 1,250 supporters in New York City. They were on their feet waving signs for their presidential candidate of choice and cheering "run, Bernie, run," reports USA Today.

"Our goal from day one has been transform this nation, and that is the fight we are going to continue," he said.

That "fight," however, rests on his fans having just as much endurance as Sanders himself, and avoiding the post-election or post-primary slump that can accompany defeated candidates' once-energized base.

Sanders himself plans to campaign to defeat Donald Trump and to "make sure that the Democratic Party not only has the most progressive platform in the history of the Democratic Party, but that that platform is actually implemented by elected officials," he said on CNN.

For Sanders, that means working to persuade Democrats to adopt his flagship policies such as free public college tuition, $15 minimum wage, and strong environmental protections. It also means campaigning for politicians who espouse these goals – from city level positions to state and national ones. And he can do so from a familiar perch: his seat in Congress, where the Vermont senator recently returned after a campaign hiatus. But what about his supporters?

They are loyal to Sanders; half say they won't vote for Clinton, according to a Bloomberg poll, and they've contributed more than $220 million to his campaign. Sixty percent of that came from small, individual contributions, according to Open Secrets.

But past deciding whether to vote for Ms. Clinton or Donald Trump, or libertarian candidate Gary Johnson, the question remains – where will those supporters go from here? Can they help sustain a post-presidential candidacy movement?

That's the hope of author and activist Les Leopold, director of the Labor Institute in New York.

In an article published in the Huffington Post on Friday, Mr. Leopold argues that Sanders should rally his supporters into a national organization "that would mobilize for his democratic socialist agenda" – a goal more easily accomplished with a Clinton, not a Trump, in the White House, although he's hardly a fan of Clinton's.

"We need an organizational structure that brings us together and connects our many issue and organizational silos," Leopold writes. "We should be able to go to Patterson, Pensacola or Pasadena to attend a meeting of a common organization that fights to reverse runaway inequality."

The first order of business would be what Sanders has said is his own top priority: defeat Trump. Then Leopold calls for a demonstration following the presidential inauguration in favor of free higher education and Wall Street taxation. But after that, Leopold says the Sanders’ presidential supporters could channel their momentum into forming a permanent, structured "large-scale progressive alliance."

"We need organization not just spontaneous eruptions that flower and wilt," Leopold writes.

The "flower and wilt" idea is one way to describe a familiar trend in American electoral cycles, where supporters get excited about a candidate and engaged in their campaigns, but do not sustain their civil interest long term.

"It's a definite phenomenon," says Justin Holmes, assistant professor of political science at the University of Northern Iowa. And it is especially apparent when it comes to non-presidential elections and Democrats, whose voter base – with more young, minority voters than Republicans’ – are less likely to show up at midterm elections, Dr. Holmes tells The Christian Science Monitor.

"If Sanders could build some kind of movement – and I'm not necessarily sure that he could – where he could be an asset to the Democratic party would be to energize these voters to come out in 2018," Holmes says.

When it comes to forming grass-roots movements off of failed candidates, American electoral history has some precedents. Holmes points to the Republic primary for the 1976 election, which pitted incumbent president Gerald Ford against Ronald Reagan, for example. While Reagan lost that election, the party absorbed some of the grass-roots conservatism of the Reagan supporters.

While that may be more politically oriented grass-roots activism than what Leopold is calling for in his Huffington Post article, that kind of political party change seems in line with Sanders’ plan to continue to pull Democrats to the left, in this election and in the future. In order to keep channeling his young-leaning fanbase, however, Sanders may need to buck one more trend: record lows for youth voter turnout at midterms, as per 2014 election data.