Turmoil in Mali: Is it another Somalia?

Loading...

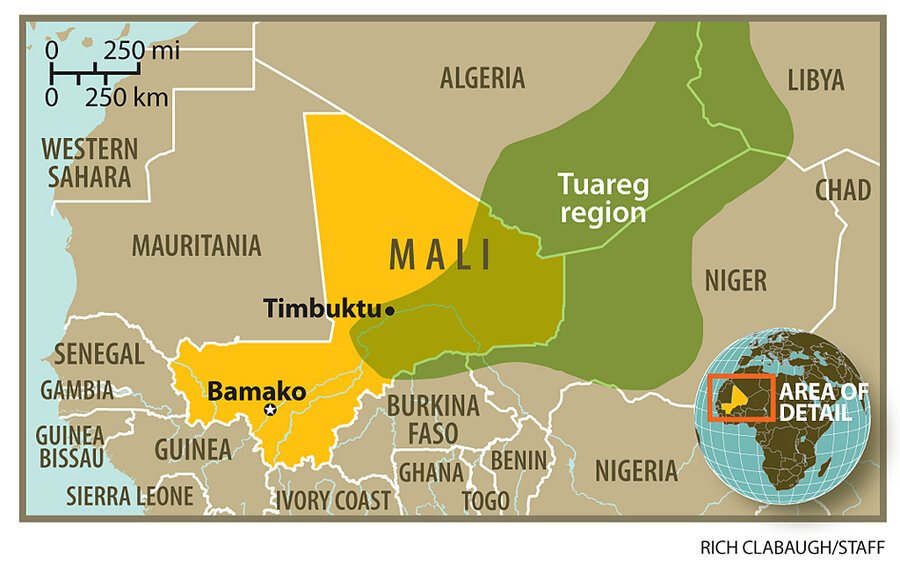

On April 6, Tuareg fighters and their Islamist allied took control of northern Mali, in West Africa. It was a stunning victory for the Tuareg fighters of the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA). The MNLA was founded in 2011, but it was just the latest of a long string of Libyan-backed rebel groups that had been fighting several West African nations for decades. But the MNLA's victory became a defeat when the MNLA's former allies, rebels affiliated with Al Qaeda, expelled the Tuareg separatists and turned northern Mali into an austere Islamist state. Security experts and West African diplomats now warn that it is turning into a terrorist haven, similar to Afghanistan, northwestern Pakistan, and Somalia. Here's what you need to know.

How does Mali's instability affect other countries and the world?

Mali's inability to govern the northern part of its country creates the opportunity for that region to be turned into a haven for extremists and criminal networks, Western security experts say. Initially, this instability has been felt mainly through kidnappings of Western tourists and aid workers, but now that rebel groups effectively control northern Mali, other West African countries such as Nigeria have argued for a regional military intervention in Mali to prevent that country from becoming a launching pad for insurgencies across the whole region. (See map here)

Did the overthrow of Muammar Qaddafi's regime in Libya prompt Tuareg fighters in Mali to overthrow their own government's control in northern Mali?

Since the 1970s, former Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi openly recruited, funded, and trained Tuareg rebels as they fought the governments of Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. When Mr. Qaddafi's government was overthrown, many of these Tuareg fighters reportedly fled to their home countries, taking their weapons with them.

The Tuareg fighters who launched the rebellion that swept through northern Mali in April 2012 include some of these Libyan-trained fighters. As Tuaregs took over the north, Malian Army soldiers launched a coup d'état in the south to protest their government's inability to arm them properly; the distraction made the Tuaregs' rebellion simpler.

Why do Tuaregs want a separate country called Azawad?

Tuaregs say that the national boundaries drawn by European colonial powers and inherited by African governments after independence have divided up the vast Sahara region they have always considered to be their homeland, a place they call Azawad (see map).

Tuaregs say they simply want to continue to live as they always have: moving their herds from oasis to oasis and trading goods across the vast Sahara without regard to borders.

And while most Tuaregs are Muslims, their official documents describe their cause as largely secular and cultural.

How is Al Qaeda making its presence felt in northern Mali?

Initially allies of the Tuareg rebels, Islamist fighters from the Algerian-based Al Qaeda of the Islamic Maghreb and Ansar Dine -- some of whose fighters are themselves ethnic Tuaregs -- succeeded in pushing the MNLA fighters out of the towns of northern Mali. Tens of thousands of noncombatant Malians from the north (Muslim, Christian, Tuareg, Arab, and others) have fled to neighboring countries such as Mauritania, straining local food supplies.

Meanwhile, Islamist groups rapidly set about remaking northern cities like Timbuktu and Gao in their Islamic image, destroying the ancient tombs of local Islamic clerics, which the modern-day Islamist fighters consider to be heretical.

While some West African leaders are calling for military intervention, the International Crisis Group says that the instability in northern Mali is largely contained within northern Mali, and that military intervention might spread the conflict to Mali's neighbors, in the same way that the overthrow of Qaddafi destabilized Mali.