US seeks to counter Chinese influence in the Global South. Is it too late?

Loading...

| London

Even as the clock ticks down to an election that will decide U.S. policy on hot wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, it’s becoming increasingly clear that a major “soft power” challenge also awaits whoever wins the White House.

The battlefield will be what many call the Global South, the broad collection of nations that are not formally aligned with any of the great powers. The challenge will be to convince such nations that they share interests – and can find common ground – with the West. That will pit Washington and its allies against Russia and China.

And in the past week, three dramatically different economic meetings have underscored the growing importance that both sides attach to its outcome.

Why We Wrote This

China and Russia have so far set the pace in building economic and political ties with Global South nations. Can Western governments match their appeal? That’s their goal.

The gatherings also provided a snapshot of where the contest currently stands: America’s rivals, above all China, have been making much greater economic and political advances with the countries of the Global South.

But Washington and the West are pushing back.

The most high-profile meeting took place in the Russian city of Kazan.

Hosted by President Vladimir Putin, it brought together the BRICS countries, named for the five core members of the 8-year-old group – Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.

China and Russia see the now-expanding partnership as a way of demonstrating – and, they hope, accelerating – what they see as the West’s shrinking influence.

For Mr. Putin, the key context is Ukraine. He framed the summit, at which he hosted 36 world leaders, as proof that Washington and its allies had failed to isolate him internationally since he invaded Ukraine.

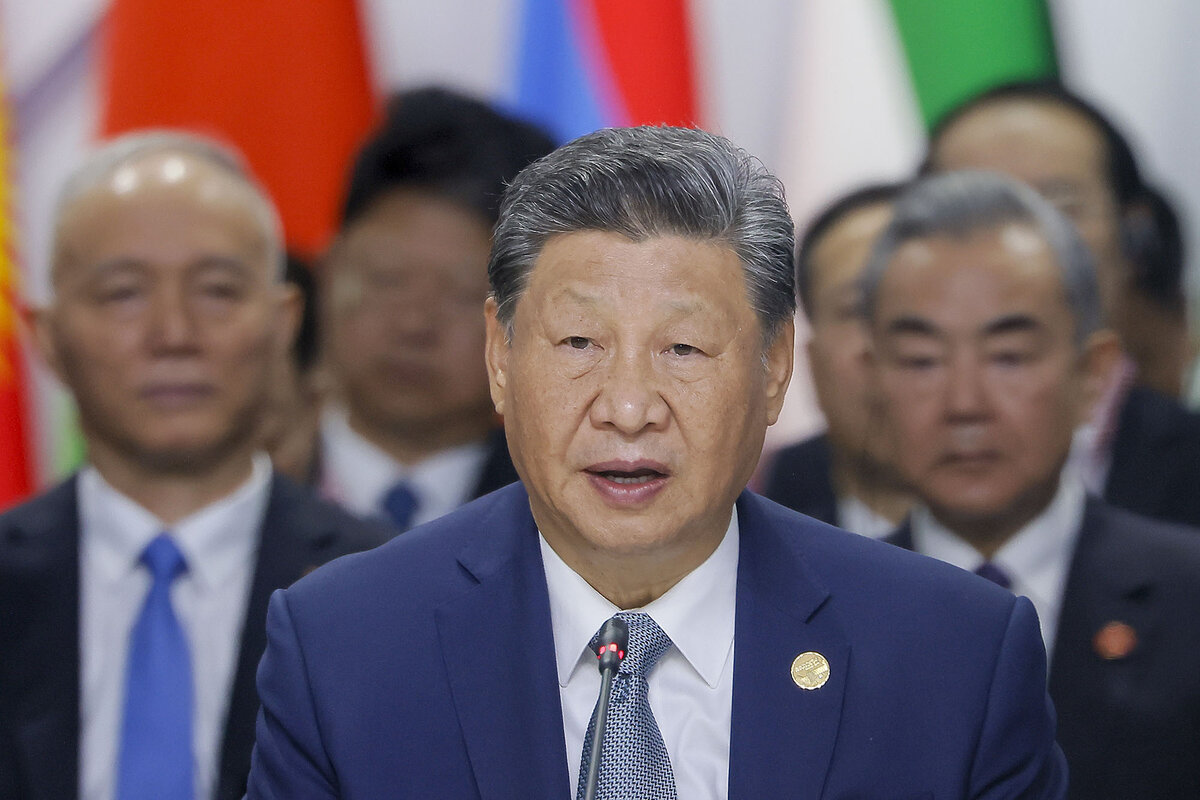

For Chinese leader Xi Jinping, it is one of two prongs in a more ambitious project: positioning his country to rival, and ultimately surpass, America’s power and sway in the world.

The first prong is BRICS, and China’s membership in it. The other prong is a $1 trillion loan and investment program called Belt and Road, through which China has been rolling out major infrastructure projects across the Global South.

Among the attractions for beneficiaries has been that China’s help comes without the kind of economic and political conditions that U.S. and Western donors have long emphasized: economic sustainability, transparency, and a broad acceptance of democratic norms.

That’s where the past week’s other, lower-key economic meetings come in.

They provided a window into how the United States and its allies are seeking to match the appeal of the Belt and Road and BRICS with initiatives of their own.

In Washington, the twin pillars of the international economic system built by America and Europe after World War II – the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund – held their annual meetings.

The IMF clearly had the Belt and Road in mind – especially the huge debt burden some Chinese infrastructure deals have imposed – when it announced significant changes to its lending terms.

The IMF said it was slashing “charges and surcharges” on its loans by more than 30%, potentially saving borrowers $1.2 billion, and that it would also expand its own lending capacity.

On the political front, it announced that its executive board would add a member: from sub-Saharan Africa.

The Western response was even clearer at a meeting of the G7 group of major world economies in Pescara, on the eastern coast of Italy, the group’s current chair.

The discussion focused on infrastructure projects for developing nations in the Global South. The plans are part of the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment, an idea first proposed by U.S. President Joe Biden in 2021 with the aim of providing a total of $600 billion in public and private-sector investment by 2027.

That’s proving to be a very hard lift. Only $30 billion, 5% of the target, has been raised so far, with the single largest project a major cross-African rail link known as the Lobito Corridor.

But the overall approach is deliberately different from the Belt and Road: ensuring the projects do not lead recipient countries into debt traps and addressing a broad range of development priorities including digital infrastructure, health provision, and climate resilience.

The hope is that this kind of partnership, over time, will prove more attractive.

But another challenge, this one political, may raise its head.

Not only are Chinese and Russian “values free” partnerships enticing for many leaders in the Global South. But Washington’s approach to world affairs in recent years, not least in the Middle East, has fed disillusion with American leadership among those countries.

Still, a number of Global South nations, including key BRICS members India and Brazil, have been equally reluctant to draw too close to Beijing or Moscow. They do not want to make BRICS an explicitly anti-Western alliance.

A recent worldwide survey by the Pew Research Institute may also encourage Western hopes that institutions like the IMF could yet find fertile ground for their new initiatives.

The survey did find falling confidence that President Biden would “do the right thing” in world affairs: only 43% agreed with that.

But the corresponding figure for Mr. Xi was 24%.

And for Mr. Putin, just 21%.