Ethnic violence: Why Kenya is not another Rwanda

| Nairobi, Kenya

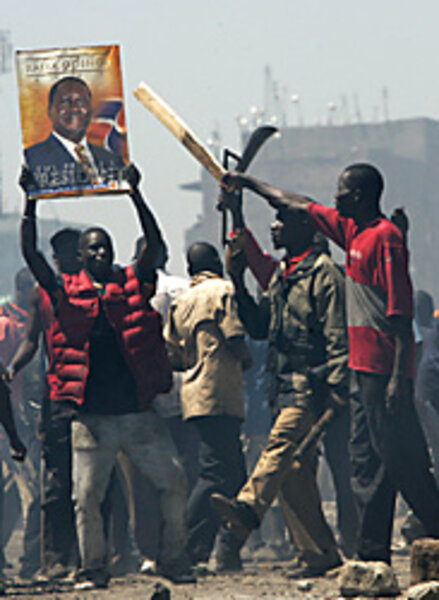

The ethnic violence that has killed more than 300 people since last Thursday's disputed presidential election has come as a shock for many here in East Africa's most stable and prosperous country.

It carries echoes of Rwanda's 1994 genocide in which more than 800,000 Tutsis were slaughtered in 100 days and it is prompting a flurry of diplomatic activity.

While President Mwai Kibaki and his populist rival Raila Odinga were accusing one another of stoking the ethnic strife, Kenya suffered its worst outbreak of violence yet on Tuesday. An estimated 30 Kenyans of the Kikuyu ethnic group – many of them children – were burned alive after taking shelter from a mob in a church in the western town of Eldoret.

"If you look at what happened in Eldoret, it's genocidal," says Abdullah Ahmed Nasir, a political observer and former chair of the Law Society of Kenya. "It has echoes of Rwanda, and this could be the start of a wave of revenge. If people are killing Kikuyus because they are Kikuyus, then definitely it will spread elsewhere to other [ethnic] communities."

"The only way to stop this is for [Kibaki] and [Odinga] to agree on a way forward," Mr. Nasir adds. "If they can agree to an interim government, and then hold elections again in one year's time, then all this could stop."

But getting these two men to agree will take international pressure, Nasir adds. "If Kibaki is pushed to talk, and if the international community can put pressure on Raila, they can agree to meet, and move toward a solution."

In an apparent olive branch to Odinga, Kibaki invited all members of the new opposition-dominated parliament to a meeting Wednesday at State House in Nairobi. But no opposition MPs attended as Odinga demanded outside mediation.

British Prime Minister Gordon Brown said Wednesday that Ghanaian President and African Union Chairman John Kufuor would go and would meet Kibaki and Odinga on Thursday.

Kibaki's tenuous hold on power took a shock Tuesday, as Kenya's chief election official, Samuel Kivuitu, admitted that he was "under pressure" to pronounce Kibaki the winner on Sunday, and that he did "not know whether Kibaki won the election."

"We are the culprits as a commission," Mr. Kivuitu told reporters Tuesday, after meeting with the 22 other members of the Electoral Commission of Kenya. "We have to leave it to an independent group to investigate what actually went wrong."

On Tuesday, chief European Union election observer Alexander Lambsdorff also delivered a blow to Kibaki's legitimacy as president, by announcing that he and his observer group noticed significant irregularities in the way in which the election results were tabulated by Kenya's election workers, and thus, had "doubts about the results."

Echoes of Rwanda

The overtones of Rwanda's 1994 genocide are ominous, but Kenya's ethnic strife differs from that of Rwanda in crucial ways.

The Rwandan genocide had been planned well in advance. State radio had demonized the economically powerful Tutsi minority for years, and after the apparent assassination of President Juvenal Habyarimina, that same state radio urged Rwandan Hutus to kill Tutsis in large numbers.

Hutus were supplied with machetes to do the job, urged on by local officials – and even parish priests – to not rest until "the work was done."

Kenya's ethnic strife, by contrast, is being carried out on a much smaller scale by many different actors. Much of the violence is focused on the economically and politically dominant Kikuyu group, but the attacks lack the Rwandan genocide's organization and preparation, and there is no evidence that Kenyan officials are organizing it. To the contary, all TV and radio stations have been temporarily forbidden to broadcast live and all news is heavily censored for the time being.

The danger in Kenya, however, lies in the intransigence of the two main leaders, both of whom claim to be president after last week's vote.

Raila Odinga has called for his supporters to hold a mass rally on Thursday in Uhuru Park in the center of Nairobi. A similar rally was effectively shut down by Kenyan police and paramilitary forces, who closed all routes into the city, declared a city wide curfew, and announced shoot-to-kill orders for soldiers stationed around the slum neighborhood of Kibera, which forms Odinga's main support base.

In Kibera itself, residents predicted that the country would erupt into further violence if Odinga's rally is banned. "If people are not given the chance to go to Uhuru park to hear what Raila has to say, there will be a lot of fire in the country tomorrow," says Peter Obuto, a civil servant. But if they are allowed to gather, "when Raila tells the people to cool down, they will do it."

Prices skyrocketing

The streets of Kibera have become an obstacle course of charred cars and minivans. Prices for milk and bread have doubled, and cooking fuel is simply not to be found. "The food sold in Kibera comes from the Kikuyu people, and they are really helping us," says Mr. Obutu. "But because of the perception that the Kikuyus don't want to give up power, the Luos, Kalingens, Luhyas, Kissis, and Kambas are ganging up on them. And we, the common people, are suffering."

As Obuto speaks, a crowd gathers to talk to a visiting reporter. But within minutes, a gang armed with machetes walks up, and shouts at the crowd to disperse. "Disperse immediately, or we will burn that car," a man shouts in Swahili.

A few miles away, close to Uhuru Park, Father Francis gives advice to parishioners who are deeply troubled by the violence and looking for their church to lend its help for peace.

"It is not enough to kneel and pray," he says. "We tell parishioners that whatever they do, they must do something that will affect peace somehow."