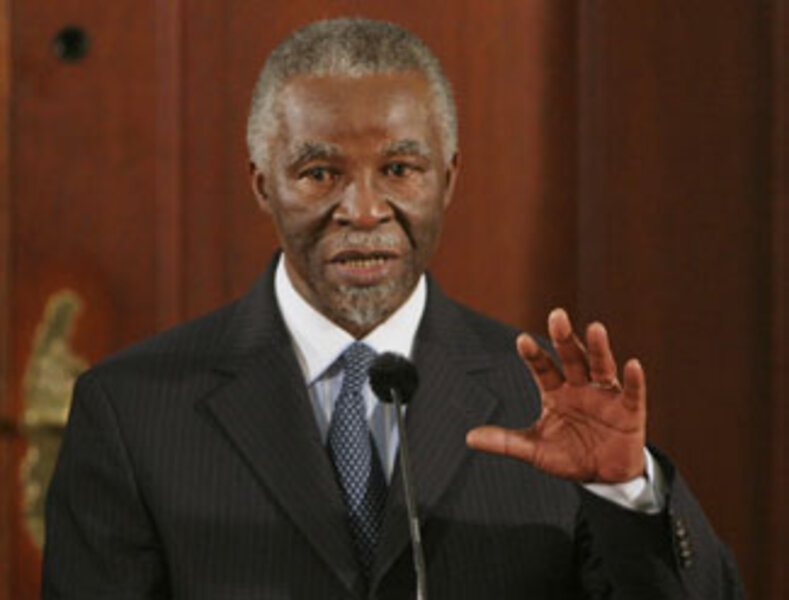

Thabo Mbeki: the fall of Africa's Shakespearean figure

| Johannesburg, South Africa

In exile, Thabo Mbeki excelled at the secretive work of building left-wing support for his liberation movement, the African National Congress.

As president, Thabo Mbeki succeeded in creating an African Renaissance – securing a decade-long economic expansion, nurturing a rising black South African middle class, and defining a new African diplomacy, where African leaders solve African problems themselves – without Western intervention.

Now that Mr. Mbeki has been ousted this weekend by his own party, he is likely to be remembered as much for his failures – to recognize the mounting AIDS crisis, to extend the nation's prosperity to its poor majority, to deal with rising crime and government corruption – as for his successes.

"He's a highly intelligent man with a firm grasp of policy issues, and he's often way ahead of the debate; he's also surrounded himself with highly intelligent people," says Steven Friedman, director of the Center for the Study of Democracy at the University of Johannesburg. "But I think this shows that you can have a highly intelligent leader who doesn't keep contact with at the base level of the voters. If you don't reach out to people, then it's not going to fly."

The announcement on Saturday that South Africa's president would be "recalled" by his own party sent reverberations throughout the region. After all, South Africa is the largest and most developed economy on the continent. Its political leadership has been involved in peaceful mediation in Ivory Coast and Zimbabwe, its troops serve in African Union peacekeeping missions in Sudan, and its political reforms have helped bring the notion of government accountability to the continent. Mbeki's absence, even a temporary leadership vacuum, will easily be felt in capitals as far away as Dakar and Djibouti, Lagos and Khartoum.

"He has a strong legacy in terms of what he has pioneered, with African constitutional governance and guiding the country through an economic expansion," says Francis Kornegay, a senior fellow at the Center for Policy Studies in Johannesburg. "He has to be given credit for that even as they are booting him out. It's a mixed legacy."

On Saturday, President Mbeki announced that he had accepted the request of the African National Congress's (ANC) National Executive Council to resign as president. His resignation will not be immediate and is likely to follow after his party nominates a successor within 30 days of his resignation. Mbeki's replacement must be a member of parliament.

The Zuma factor

Mbeki's downfall comes just a week after the collapse of a lengthy corruption case against Mbeki's personal rival, Jacob Zuma. In 2005, Mbeki fired Mr. Zuma as his deputy president after Zuma's financial adviser was found guilty of soliciting bribes from a French weaponsmaker in a major procurement scandal.

Zuma resurrected his career in December 2007 by being elected over Mbeki as president of the ANC, a post that is generally held by the party's heir apparent to the presidency of the country.

Mbeki's loss will not immediately be Zuma's gain. Zuma – a one-time intelligence chief of the ANC's military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe – is not currently a member of parliament and so cannot be selected as Mbeki's immediate successor. Instead, he is likely to take over when national elections are held in March or April of 2009.

While Mbeki's deputy president, Phumzile Mlambo-Ncquka, has announced that she would hand in her resignation at the same time as Mbeki, other cabinet members have not yet followed suit. Finance Minister Trevor Manuel, who, together with Mbeki, is credited with keeping government spending down and creating an investment climate that helped steer South Africa's postapartheid expansion, has announced that he has no immediate plans of stepping down.

Baleka Mbete, the speaker of the National Assembly and chairwoman of the ANC, is widely expected to take over for Mbeki.

At press time Sunday, Mbeki was holding a cabinet meeting. After the meeting, Mbeki and Zuma were expected to address the nation on state television to reassure the public that an orderly transition was under way.

In the past nine months as the ANC president, Zuma has carefully reassured business leaders he would follow in the market-friendly footsteps of his predecessors, despite his close ties to left-wing allies in the ANC-ruling coalition, specifically the Confederation of South African Trades Unions, the ANC Youth League, and the small but influential South African Communist Party.

The populist

But Zuma would bring a populist touch to the presidency nonetheless, and his strong support in the townships and rural areas are testament to a personal charisma that Mbeki either lacks, or disdains.

In his biography of the reclusive Mbeki, Mark Gevisser reveals that Mbeki, as a young economics student at the Lenin Institute in Moscow in 1969, closely identified with the tragic Shakespearean character, Coriolanus. Mbeki saw Coriolanus as a revolutionary role model who was prepared to go to war with his own people to defend the nation's principles. In the end, Coriolanus is exiled because of his unwillingness to publicly parade after returning from a successful campaign.

Mr. Gevisser suggested that Mbeki saw his own future in Coriolanus. "The person who does good, and does it honestly, must expect to be overpowered by forces of evil," he told Gevisser during a 1999 interview. "But it would be incorrect not to do good just because you know death is coming."