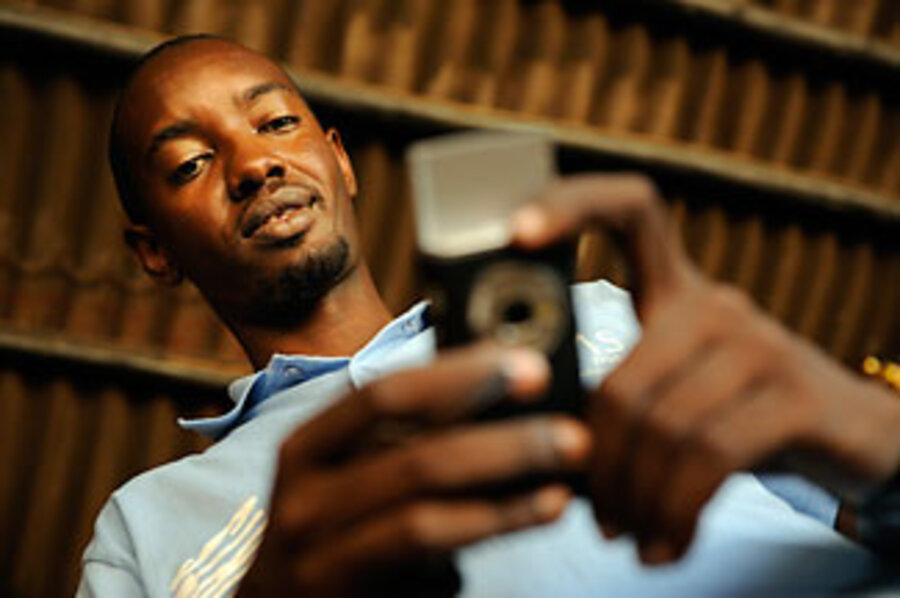

A texting entrepreneur embodies spirit of a new Rwanda

| Kigali, Rwanda

Jeff Gasana is a man on a texting mission.

The soft-spoken 20-something tycoon thumbs his sleek cellphone, firing off SMS messages to associates, his deadpan calm belying the ferocity of his drive for success.

His goal is to make SMS Media, the text-messaging firm he co-founded six years ago, the leading cellphone banking service in East Africa, where cellphone-to-cellphone finance is emerging as an enormous business opportunity.

In Rwanda, SMS Media is already an award-winning industry leader in allowing customers to purchase and activate prepaid amounts of electricity via cellphone. A full 40 percent of Rwandans now buy electricity using the company's services.

Mr. Gasana embodies the spirit of a new Rwanda. Just 15 years ago this week, Hutu extremists here began slaughtering Tutsis and moderate Hutus, killing more than 800,000 in less than 100 days, the worst ethnic killing since the Holocaust. The genocide tore apart the country's social fabric and institutions and destroyed its economy; Rwanda survived on emergency food aid until 2000. But the past few years have seen remarkable economic progress – skyrocketing Rwanda from a regional backwater to a can-do hub for technology and trade.

The Singapore of Africa

Now, Rwanda's butter-smooth roads are the envy of Africa, investors are pouring money in, and modern glass office buildings line the hills of the capital, Kigali, helping the country earn its status as the "Singapore of Africa."

But there's a dark side to the success. Few outside the highly educated circles in Kigali are benefiting from the prosperity. More than 80 percent of the population is still getting by on less than $2 a day, struggling as the cost of living leaps. The boom is also the result of a tightly controlled, Tutsi-dominated government that critics say stacks the deck in favor of Tutsis and stifles all dissent.

"Nothing was here [after the genocide] in 1994. The infrastructure was zero," says Mr. Gasana, between a flurry business calls. "Up until 2000, all my friends left the country for the US or Europe, because there was no future for them here. But since 2005, many young Rwandans are coming back to work and start companies. I'm very impressed with the way the country is growing, Investors are coming. Many companies are opening up shop. The government is pushing IT [information technology] a lot. That's good news."

Technology products come in tax free

Rwanda's economy grew at a record 11 percent in 2008, and much of the focus for growth has been on transforming the country from a subsistence economy to a knowledge-based one. The government gives information and communication-technology firms a free location to start their business for the first year. It also sponsors trips for IT businesses and technology exhibitions. Rwanda is also the only country in the region to allow IT products into the country tax-free.

All these moves have helped young techies like Gasana get their start.

Drawn to Rwanda for good jobs

And it's not just Rwandans finding success here. Young professionals from more-prosperous countries like Kenya and Uganda are now being drawn to Kigali by the job opportunities.

Take Peter Kazibwe. The graphic designer arrived last May to earn six times what he was earning in his native Uganda. "There's a much higher demand for people in my field here," says Mr. Kazibwe.

Also among those eager to get out into Kigali's working world and make his fortune is Jeff Madali, a Rwandan who graduated at the end of March with a bachelor's degree in marketing from the School of Finance and Banking, the only business school in the country.

"We can now graduate, get a good job, and hang out here," says Mr. Madali, gesturing toward the posh coffee shop where he and his up-and-coming peers gather for $3 cappuccinos and overpriced snacks.

"I enjoy marketing. I like to go out, see where the company is weak, and improve it," says Madali, listing ways the tourism company he interned with could care better for the rapidly growing number of foreigners visiting Rwanda for gorilla safaris.

Both of Madali's parents lost many relatives in the 1994 genocide. His girlfriend lost both her parents and six of her 10 siblings during the killing. "This is the time I feel so sad about those things," he says, explaining that, since the genocide, April 7-30 has become a mourning period.

But the country is moving on, Madali says, adding that the government preaches about how to forgive. "At university, you study with Hutus, but maybe they aren't the ones who killed. Why should we hate them?"

Incubator for entrepreneurs

At the School of Finance and Banking, Hutu and Tutsi students mingle with many other ethnicities from all over the region.

Third-year marketing student Patrick Ntwale, however, is not waiting until he graduates next year to start his career. He runs his own business selling collectors' stamps online.

"Online, it's easy to create business, because the whole world can be your market," he says, adding that he studies E-Bay and Amazon.com for good business strategies. He's also joined others to create a firm that makes educational movies.

"When you start a business, you have to take a risk," says Mr. Ntwale. "Sometimes you fail, but you have to keep going. Our president [Paul Kagame] says you have to create your own business, not wait for someone to hire you. People used to just graduate and expect a job, but if I don't start my own business today, I won't do business in the future."

That's the kind of entrepreneurial spirit the school's outgoing South African rector, Krishna Govender, hopes will be his legacy when he finishes his three-year stint in charge this month.

"Getting the culture right was a huge challenge," says Mr. Govender, explaining how workshops in time and performance management helped students who weren't even showing up to class graduate ready to manage a business team.

"I'm not a religious person, but maybe this has been a sort of calling for me," Govender says. "Our institution is very relevant to the progress of the country. Rwandans should be using [President Kennedy's] statement: 'Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.' Everyone should be saying: It's my responsibility to change this country. The president is very clear on this. I like his thinking."

What economic boom?

Not everyone is so gung-ho about the country's future.

All over Kigali, shantytowns are being torn down in order to build new developments for wealthy Rwandans and foreigners to buy big new homes.

It's part of the president's vision of a modern African nation. The economic boom is causing prices to rise rapidly, but many lower-income people say their earnings are not keeping pace.

"It's too hard to survive," says Jean-Marie Safari, who picks up odd jobs in construction when he can. "Things are getting more expensive everyday. Food, rent … it's all going up."

"Sometimes we don't eat," says Chantal Ingabire, who sells sodas at a makeshift store in Kigali's impoverished Kacyiru neighborhood.

Eliab Murwarashyaka came to Kigali from a village in southern Rwanda two years ago in search of a better life, but, he says, he doesn't have the necessary education to get any of the new jobs being created.

He makes 30,000 Rwandan francs ($52) per month working at a bread factory, and sends that amount back to his family in the village every three of four months. Rent has doubled since he arrived. "I don't think I can get married," he says. "I can't make enough money to support a family."

"Those with money," says Mr. Murwarashyaka, "they're going up. The poor are just going down."

Throughout the poorer neighborhoods of Kigali, the anger is palpable, but is often expressed only in hushed tones.

Prosperity with a price?

Like Singapore under Lee Kwan Yew in the 1970s, '80s, and '90s, today's Rwanda is gripped so tightly by Mr. Kagame's government that people are afraid to voice criticism.

"You can't say anything publicly in Rwanda if it's critical of the government," says one opposition party member who refused to be named for fear of retribution. "We want freedom of speech, but we don't have it. Even in the ruling party, there's no freedom of speech. In Rwanda, we have only one politician: President Paul Kagame. They want to applaud him and kneel before him....

"People are angry, but they fear," he says, claiming that the country's 80 percent majority of Hutus are being unfairly treated by the president's Tutsi-dominated government. "It's unequal here. It's hard to get a decent job if you're Hutu. It's almost all Tutsis that have good jobs in public sector. Nepotism is rife. Very few Hutus have decent wealth."

The government consistently denies all charges of favoritism, pointing to its ban five years ago of the use of the terms Tutsi or Hutu as evidence of the ethnicity-blind society it says it is working hard to foster.

Andrew Tusabe, a diplomat at the Rwandan Embassy in Washington, calls those types of allegations "baseless."

"It's propaganda pushed by people in exile," he says. "There's no more Hutu, Tutsi in this country. Jobs are based on merit. There's no favoritism at all. People who have the competency get the jobs. There's no nepotism."

Meanwhile, rights groups consistently point out the repressive nature of the government.

"The legislative and judicial branches of government have done little to counterbalance the executive or mitigate the influence of the military in policymaking," according to a 2007 report by Freedom House, a rights advocacy group in Washington. "In practice, power remains concentrated in the hands of a small inner circle of military and civilian elites…. Critical voices in civil society and the media have been almost completely silenced."

Freedom House ranked Rwanda 181 out of 195 countries in its 2008 Freedom of the Press survey. That's tied with China, just above Zimbabwe, and not far above the world's most restrictive authoritarian regimes, such as North Korea, Turkmenistan, and Cuba.

"Tutsis fear Hutus. They have robbed power from Hutus. Their position is not legitimate," says the opposition politician. "They say there's reconciliation, but it's just talk," he says as he nervously unlocks his office door and peers down the hallway outside his office. "I check because every day, people follow me to see who visits me. At any hour, I'm ready to die. I ask God that I die without being tortured."

In the village of Mulindi, just a few miles outside of Kigali, Damascene Bakunzi, a Hutu, says he used to be a cashier of a transport company before the genocide, but has since been forced to sell used clothes at the market.

He says he studied law and could be a paralegal, but can't get a job because he is a Hutu. "I'm not alone," he says. "There are many like me. Hutus are very angry, but they can't show it."

How one Hutu prospers

Back in Kigali, however, one Hutu at least is doing quite well.

Emmanuel Ngomiraronka is a marketing consultant for the Rwanda Coffee Authority. He holds a doctorate in political economy from Peking University. After teaching English and studying in China, he began to export Rwandan coffee to China to meet the growing demand for coffee there.

Now, he's based in Kigali and partners with a Chinese company that earns 30 percent of the proceeds of the coffee he ships. He says Rwanda is very pro-business and investor-friendly. By way of example, he explains how the Rwandan Development Board allows foreign companies to register, get a business license, insure the firm, and get a taxpayer license – all in one day, at the same place. "It takes three to four days – and stops to different offices – to do the same things in Hong Kong," he says.

"From 1994 to 1999, Rwanda was surviving on emergency foreign aid. Ten years ago, the business environment was not taken seriously," says Ngomiraronka. "Government policies have played a big role in the growing economy. I really believe Rwanda has made big steps."

Pay the electric bill on a cellphone

Text-messaging guru Gasana agrees. Those who use his service to pay for their electricity buy small scratch cards that have a code signifying a prepaid amount. When they enter the code into their cellphones, the electricity is turned on for their house for the period of time they purchased.

This system has created thousands of jobs throughout the country for small-time dealers who sell the cards and earn a 5 percent commission. The system is seen as a model for how developing countries can efficiently provide electricity, and has won the firm five international awards.

Many African countries and companies have approached Gasana about setting up electricity payments via cellphone. Later this year, he'll help Mozambique become the first country outside of Rwanda to make use of his payment system.

In the fall, he'll travel to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge to speak about his work at an international conference.

Like many of his peers making it big in the new Rwanda, he uses his limited free time to enjoy his disposable income. He likes to go to parties, he says. He also likes to go to national parks in the region that are typically visited mostly by well-heeled Westerners. Tanzania's Serengeti National Park tops them all, he says.

But Gasana says he's not motivated by the perks of wealth as much as the mission of job creation. "I've seen lots of people change their lives," he says, "with the small business they can do by being independent dealers of my SMS products."

Despite his youth – Gasana is not yet 30 – he is the office elder. He wouldn't have it any other way.

"I'm informal in my office. I like to let people feel free. It helps them come up with ideas," he says. Lest anyone get the wrong idea about the work ethic of his young team, however, he adds with a smile: "But we have lots of goals, too."

• Last in a three-part series. Part 1 ran on April 7, Part 2 on April 8.