Can Mutambara save Zimbabwe's power-sharing government?

Loading...

| Johannesburg, South Africa; and Harare, Zimbabwe

For the second week running, President Robert Mugabe's coalition partners – the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) – have boycotted cabinet meetings. It's the latest sign that the country's fragile power-sharing agreement could collapse.

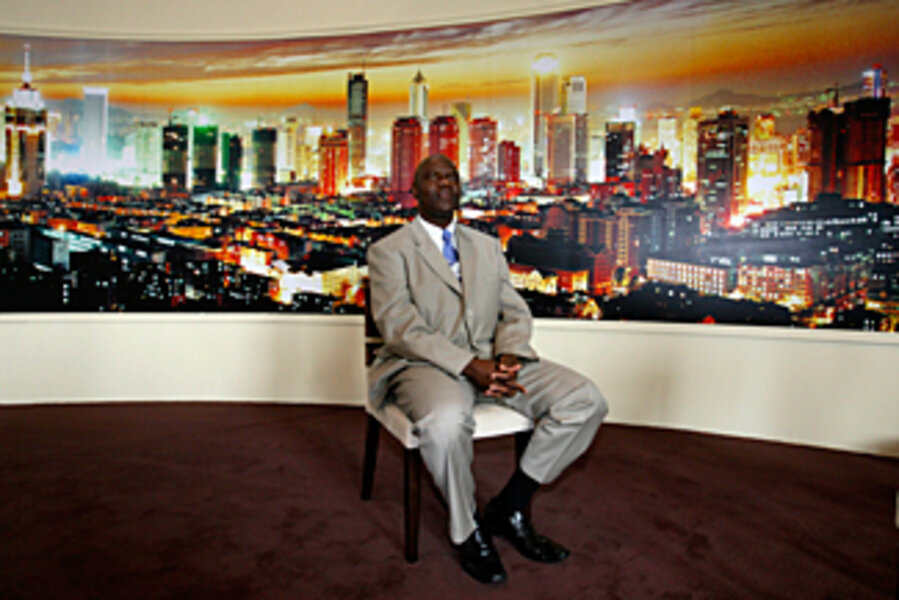

But this doesn't mean that Mr. Mugabe's ZANU-PF party has the government all to itself. Arthur Mutambara, the country's deputy prime minister and leader of a smaller faction of the MDC, and other members of his party attended cabinet meetings this week in a bid to hold the so-called Government of National Unity together.

Mr. Mutambara this week portrayed himself as a mediator, while heaping criticism on both Mugabe and his own fellow opposition leader, Morgan Tsvangirai, for their obstinance.

"Tsvangirai should not have [disengaged from the unity government] since we need to fight Mugabe from within," Mutambara told reporters on Sunday. As for Mugabe, Mutambara said, "If the [coalition government] collapses, we are telling Mugabe that he will be like a rebel leader and not president of the country. I have told him to shape up or ship out and I am still maintaining that."

Those are tough words for a man whose party performed poorly in the March 2008 elections, and today controls only three out of 31 cabinet seats. While Mr. Mutambara has managed to organize a Monday meeting between Tsvangirai and Mugabe – a meeting that served only to drive the two leaders further apart – political observers say that Mutambara's short track record reveals a volatile, opportunistic man with limited clout.

"Arthur Mutambara has neither the gravitas nor the support in the country and in the parliament to play a useful mediating role between Mugabe and Tsvangirai," says Marian Tupy, a Zimbabwe expert at the Cato Institute in Washington. "He's fundamentally volatile and even people within his own faction are incredibly disappointed in his performance as deputy prime minister so far."

Unity government down, but not out

That Zimbabwe's coalition government is in trouble is not surprising, says Judy Smith-Höhn, a senior researcher at the Institute for Security Studies in Tshwane (Pretoria). The generals who controlled much of the day-to-day running of Zimbabwe's government were not brought into the negotiating process and so they can play a role as potential spoilers if they feel threatened by political change, she says. In a further sign that Mugabe's party does not take the opposition seriously, Zimbabwe's National Security Council, its top decision-making body on security issues, has only officially met once in the past eight months. "I don't think that the ZANU-PF has changed tactics since September, when it signed the agreement," says Ms. Smith-Höhn. "They are doing the same thing they did before."

That said, Smith-Höhn believes that outside pressure – particularly from the Southern African Development Community (SADC) – combined with internal pressure from moderate politicians on both sides can still push the fractious coalition government back together.

Since beginning his boycott Tsvangirai has met with several regional leaders, among them South African President Jacob Zuma, Mozambican President Armando Guebuza, and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) President Joseph Kabila, who is the current chairman of the SADC. But it doesn't appear that those meetings have borne much fruit for the embattled MDC leader. The SADC's security committee is due to meet in Harare on Thursday.

Why Mutambara may not have enough sway

While Tsvangirai was trying to drum up regional support, Mutambara told a press conference last week that he was mediating between Mugabe and Tsvangirai to bring normalcy to the inclusive government, and that his "MDC-M" faction would attempt to bring the larger, more powerful "MDC-T" back into the unity government.

"We are in the middle of ZANU-PF and MDC-T," said Mutambara. "We will use this position to make sure that we encourage dialogue between these two major political parties in the country. We will use this position to push for the national interest and for mitigating differences."

University of Zimbabwe political scientist John Makumbe says Mutambara's efforts to mediate in the crisis are unlikely to succeed, because he does not have the political clout to sway Tsvangirai or Mugabe.

"He will not be effective. Not at all, because he is just a small pin standing between two giants with differing political interests," said Mr. Makumbe. Mutambara was wasting his effort trying to convince Mugabe, Makumbe added, because Mugabe has been resisting pressure from both the SADC and the African Union (AU), who are the guarantors of the agreement.

Simon Badza, another University of Zimbabwe political commentator, added that the future of the inclusive government will be determined more by ZANU-PF and MDC-T's "strategic interests" than Mutambara. "I think Mutambara is an opportunist and he thrives on crisis in the government of national unity," said Badza. "He is not a big factor in the inclusive government."

• Our reporter in Harare could not be named due to security concerns.