As World Cup 2010 kicks off, where South Africa stands 16 years after apartheid

| Johannesburg, South Africa

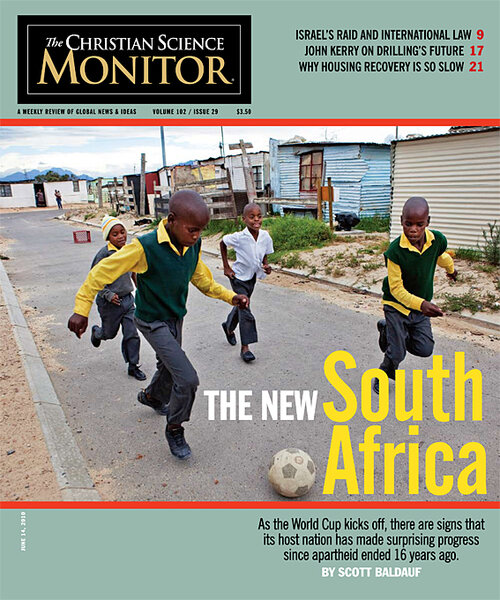

The South Africa that hundreds of thousands of soccer fans will visit this month during the World Cup will take many people by surprise.

In Johannesburg, skyscrapers loom where rolling Highveld prairie once stood. In Cape Town and Durban, and even the stoutly midwestern city of Bloemfontein, smoothly paved highways, world-class airports, and posh hotels flourish amid South Africa's temperate, Mediterranean climate.

The insurgent and impoverished black townships that would have been do-not-enter zones in the early 1990s have now become tourist havens. The most famous of them all – Soweto, site of riots well into the 1990s – is ribboned with bed-and-breakfasts, gated communities, and shopping malls. It will play host to the opening ceremony and game in the spectacular new Soccer City stadium, with speckled panels that make it look like a gigantic calabash gourd. Or a poppy-seed bagel, if you prefer.

IN PICTURES: South Africa: Sixteen Years After Apartheid

The South Africa that will go on display this month is a country that has completed its transformation from a racist pariah state into a multicultural majority-led state, with many of the accouterments of a European first-world powerhouse. It is a country that has achieved much in little time, and while many South Africans fret about the direction their country is heading and others complain about the slow pace of change – and understandably so – it is also a country that 16 years after apartheid has become one of the world's premier models of racial reconciliation.

Consider the South Africa that Nelson Mandela took over in April 1994. Laws prohibited more than 80 percent of the population from voting, from living in designated "white only" areas, from access to higher education and job opportunities. The gap between rich and poor was vast, symbolized by the gold-baron mansions in Johannesburg's northern suburbs and the dusty tin-shack squatter camps and matchbox homes of Soweto.

Anger and frustration among both whites and blacks threatened a race war. Majority rule, led by Mr. Mandela's African National Congress (ANC), offered an olive branch to its former enemies and a manifesto of racial reconciliation – yet rivalries among different black parties sparked almost daily conflicts that had the potential of stealing away the country's best chance for peace.

South Africa today is not perfect, of course. Scratch the gleaming surface, and you'll find government corruption, crumbling water systems, overextended electrical power stations, declining schools, and an enduring unequal distribution of wealth. You will even find a terrifying hatred of foreigners coming to South Africa to find work, a hatred that played out two years ago in xenophobic attacks.

But how do you measure success in a country like South Africa? Do you look at the growing number of mirror-skinned high rises or at the metastasizing informal settlements filled with poor blacks searching for work? Do you look at the 1.1 million houses built for the poor and nearly 16 years of economic growth or do you look at South Africa's dubious distinction of being a country with one of the largest gaps between rich and poor, with the largest number of AIDS patients, with one of the world's highest violent crime rates, and where 47 percent of the population lives in poverty?

If South Africans seem unclear on whether to be hopeful for the future, certainly reasons exist to celebrate what progress the country has made. "Anybody telling you that South Africa is worse off has no sensibility of what is good and what is bad," says Adam Habib, deputy vice chancellor of the University of Johannesburg, who was a political activist against the apartheid government in college. "I mean, in 1985, I was sitting in prison, because of the state of emergency. So the very fact that the entire population can now vote is a huge improvement, when under apartheid 80 percent were denied that right."

In addition to political freedom, liberation has brought many benefits to the majority population, Mr. Habib says, including access to the court system, access to bank loans, and greater mobility for families to move to former white-only areas with all the advantages of better services such as electricity, sanitation, security, and schools. Under 16 years of majority rule, South Africa's black middle class has grown exponentially.

The challenge, says Miriam Altman, a social scientist at the Human Sciences Research Council in Tshwane (as Pretoria is now called), is how to manage people's expectations. "You're talking about 300 years of colonial occupation, 48 years of apartheid rule, and 16 years to come up with solutions," says Ms. Altman, who has become a member of President Zuma's newly created National Planning Commission. "There is no doubt that delivery in education and other areas needs dramatic improvement. But I certainly wouldn't say that all hope is lost. We just need to find better solutions."

The question, she adds, is, "What is it that gives people hope? We're a middle-income country. We have resources. But we also have higher expectations."

Tensions between whites and blacks certainly remain. When Eugene Terre'Blanche, the openly racist leader of the extreme right-wing party AWB, was murdered by a black employee in April, members of the organization started talking openly about a "machete race war." The fiery leader of the ANC's Youth League, Julius Malema, did not make things better by continuing to sing an apartheid-era song called "Kill the White Farmer." Both the AWB and the Youth League have since toned down their rhetoric.

Integration has been halting as well. Blacks, whites, and coloureds (mixed race)do attend some of the same schools, both private and public. Blacks who can afford to do so are moving into former white middle-class and rich neighborhoods, and there are even some middle-class whites who have moved into formerly all-black communities like Soweto. But in many schools, suburbs, and corporate suites, integration is the exception rather than the rule.

To gauge just how far the country has come, we asked two middle-class families – one white, one black – to tell of their own experiences of the past decade and a half, and their expectations for the future. Their sentiments are strikingly similar, despite differences in skin color and personal histories.

Both families give their government credit for what they have achieved, and both share disappointment about many of the same areas where they say the government has failed. Yet, both families continue to bank their future on the hope that South Africa will somehow set things right.

The Thabangs: Part of the rising but restless black middle class

When liberation came, with the election of Mandela's government on April 27, 1994, Israel Thabang was a 22-year-old college student and former ANC activist. As a black South African and member of the African National Congress, he had organized protests against the apartheid government. Liberation brought both an affirmation of his past efforts and euphoria.

"It was quite an exciting time; we couldn't believe what was happening," says Mr. Thabang, relaxing with his children on the leather couch of his comfortable townhouse apartment in Soweto. "We walked the whole of Joburg for the whole night."

Sixteen years later, Thabang can also recall the keen anxiety that many ANC supporters felt, that their country could still tumble into civil war. "The Inkatha Freedom Party was there, fighting our own people in the ANC, and you had the white Afrikaner party on the other side, threatening to separate, so no one was sure that democracy was really coming. When you look at other African countries, you worried that we might not reach our goal."

He smiles. "But miracles happened."

The South Africa that Thabang grew up in was a country torn apart by racist laws and increasingly violent protests. Raised on a farm in Limpopo, South Africa's poorest province, Thabang came to Johannesburg in the early 1990s to attend college. Mandela had been released from prison and, in 1994, he became South Africa's first black president.

The country Mandela took over functioned well when it was serving the 12 percent of the population that was white, but now it had to expand those services – electricity and education, sanitation and drinking water, health care and police protection and roads – to the black majority who made up the 80 percent who had been neglected at best.

Townships like Soweto were not only no-go zones for whites in 1994, but were often dangerous even for black residents. Today, Soweto is a neat-and-tidy black-majority suburb with better schools, supermarkets, and shopping malls, and more important, electricity, paved roads, and regular police patrols whose job is to go after criminals rather than political activists.

Thabang and his family live in a gated community of townhouses, one of the many symbols of how far this former war zone has come.

As members of a growing black middle class, the Thabangs are a living achievement of the ANC, something never contemplated by the apartheid government. But as middle-class people often are, the Thabangs are also aware of their own government's failings. With Israel earning a good salary as a paramedic for a private ambulance company and his wife, Kate, working as an environmental health officer with the local government, the couple credit their success to hard work, not handouts.

"Not everyone is happy in this country, but we're getting there," Thabang says, as his children, 10-year-old Alicia, 9-year-old Thabo, and 3-year-old Katlego, watch an afternoon cartoon on a large flat-screen television. "When I drive through Soweto, and I see young girls and boys going to school, I know it's not a privilege, it's a necessity. These days, if you don't go to school, you starve."

South Africa will only succeed if South Africans hold their government accountable, Thabang says, changing the channel (over his children's protests) to a real-time broadcast of debate in South Africa's Parliament. Thabang is disappointed in many of his country's current leaders – some of whom he says are more interested in making money than in serving their country.

He worries about hotheads like Mr. Malema of the ANC Youth League, who talk about nationalizing the country's mines and about taking away farmland from current owners, which could set the country on a path just as destructive as that of South Africa's next-door neighbor, Zimbabwe. But, Thabang says, the best part about democracy and majority rule is that voters now have the power to choose new leaders.

"You look at a party, and if they don't fulfil their mandate, then we'll say, 'we don't want this party,' " says Thabang, with a mischievous grin. (His son Thabo is grinning, too: He has taken back the remote, and changed the channel back to cartoons.) "We fear nothing now. If people say 'we want water,' they'll get water. Now, not later. If you lie, people will change you."

The Wentzels:Whites who embrace a color-blind era– but are unemployed

Ivan Wentzel has the beefy frame of an Afrikaner – the Dutch-speaking white settlers who once ruled this country during the 45 years of apartheid. His wife, Lynda, teases him that he looks like a poster boy for the right-wing AWB party.

But with Ivan and Lynda, looks are deceiving. Statistically, they are well within the white middle-class South African norm, living in a comfortable but not posh three-bedroom house. He is a college graduate, the son of a South African diplomat. She is a high school graduate, but, raised on a farm, she is fluent in Sesotho, the language of African laborers who lived around them.

Even with the end of apartheid, whites still enjoy economic advantages. They own 94 percent of the share value of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange and 81 percent of the commercial farmland in the country. Seventy percent of white college students found work immediately after graduation, higher than the rate of their black, Asian, and mixed-race classmates, according to a 2003 study conducted by the Human Sciences Research Council. It's a fact that belies the worries of many whites that their children will be disadvantaged by the government's affirmative-action programs promoting job creation for blacks.

Yet, despite these seeming advantages, the Wentzels are part of a quiet number of white South Africans who welcomed the end of apartheid in 1994, primarily because the system was unfair. They left the church they attended, the Dutch Reformed Church, because of its past support of apartheid. When a black Zimbabwean family moved into the house across the street, they didn't scowl like their neighbors did. They took them a casserole.

The Wentzels send their children, Louise, 8, and Stephanie, 6, to a mainly white Afrikaans-language public school, but they enthusiastically embrace a new color-blind era. One day, while visiting the home of a black classmate, Louise was introduced to the girl's father. "You didn't tell me your father was black," Louise told her friend. It never occurred to Louise that her friend was also black, Lynda says.

"The kids who are going to school now, they'll forget about all these issues of race, and they'll just get on with the business of being children," says Lynda, seated on a comfortable sofa in her modest home in the Centurion suburb of Tshwane. "That is the hope of this country."

The Wentzels would not, at first glance, appear to be such easy fans of an ANC government. Like the majority of South Africans in their late 30s, 40s, and 50s, both served in the military at a time when the ANC was Public Enemy No. 1.

Ivan recently retired as a major from the South African National Defense Forces, where he had worked as a French-language interpreter for the top brass. Lynda retired as a sergeant in the Air Force, in charge of arranging trips for senior officers. Both are having difficulty finding work in the private sector.

They have seen major mistakes by ANC politicians, but they say the ANC is learning and often backtracking to old apartheid-era systems that worked. They shake their heads at corruption and the rise of "tenderpreneurs," politically connected businessmen who profit from getting government tenders.

But they also note that the ANC's three presidents, Mandela, Thabo Mbeki, and now Jacob Zuma, have been careful to keep left-wing rhetoric out of their economic policies, and to ensure that a free-market system thrives and creates jobs.

Lynda is philosophical about the centerpiece of the ANC's transformation of the economy, a system called "black economic empowerment," which encourages the hiring and advancement of black employees in government offices, and rewards private companies that advance black employees in the private sector.

"In the old apartheid system, my mother worked until she was 60, not because she had skills but because she was white," says Lynda. "Now you get a job because you're black. It's just the pendulum swinging the other way."

That pendulum has come with a personal cost. Ivan left the military last month because there was no room for advancement. He tired of absorbing the duties of departing colleagues, but with no increase in pay. Now he enters the job market in a recession, his white skin no longer an advantage. Lynda is also unemployed, having retired to take a more active part in raising their daughters.

But Ivan has no time for pessimism. "It's very easy to talk about the negatives, but we love our country, we both served our country, and we still want to contribute," says Ivan. He falls silent, and Lynda finishes his thought: "If only we could find jobs to do so."

Related:

- World Cup stampede renews concern over South Africa's preparedness

- Will foreign workers flocking to World Cup face xenophobic attacks?

- Blog: World Cup 2010: South Africa deports Argentina's 'barra brava' hooligans

- Africa's AIDS Orphans

- Blog: Traveling to the World Cup? Be sure to bring ear plugs.

- World Cup - All coverage

- South Africa - All coverage

IN PICTURES: South Africa: Sixteen Years After Apartheid