Kenya's anticorruption advocates laud suspension of key minister

Loading...

| Nairobi, Kenya

Kenya’s president has suspended a key minister over a nine-year-old corruption case, raising hopes here that anti-graft laws in the country's new Constitution will be applied forcefully.

Under the new system, any minister accused of a criminal charge must stand down while his or her case is brought to court.

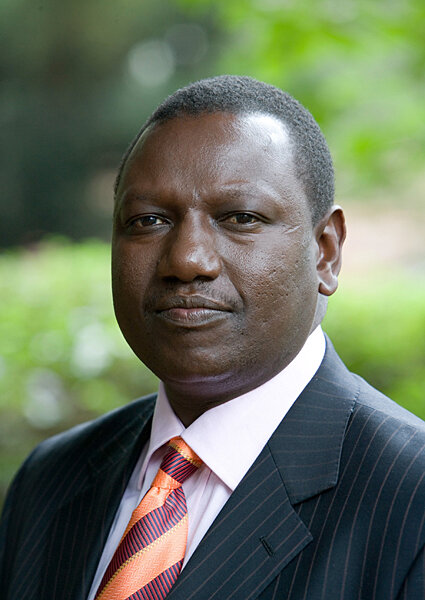

William Ruto, the higher education minister and torch-bearer for those opposed to the new Constitution, refused to step down over accusations he scooped $1.2 million in the illegal sale of land in 2001. But Kenya’s High Court last week overturned Ruto’s bid to have the case thrown out, and ordered him to stand trial.

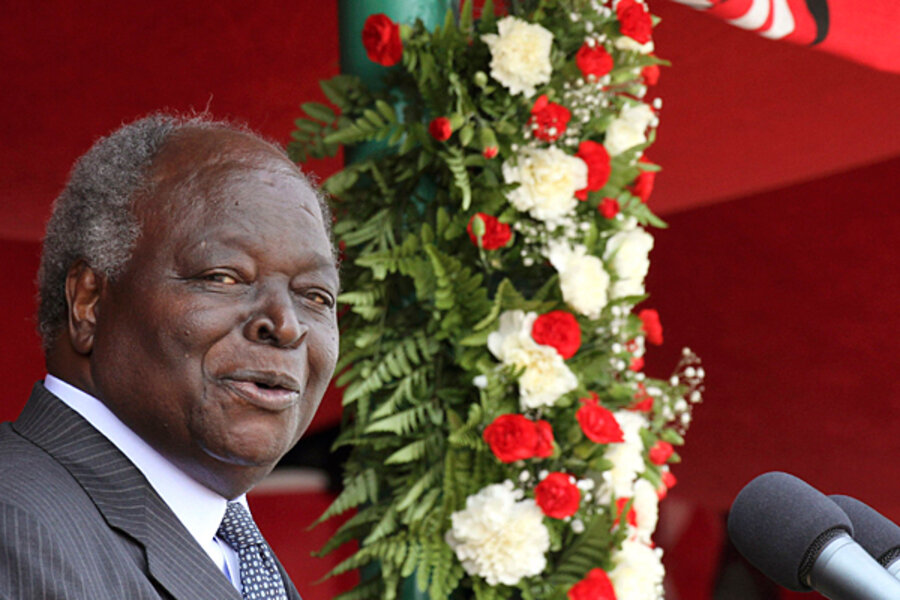

President Mwai Kibaki – who sees the new Constitution as his lasting legacy after his 10 years in office end in 2012 – then ordered Ruto out of the Cabinet on Tuesday.

“Kibaki is facing a huge amount of pressure to see that the integrity chapters of the Constitution are implemented,” says Mwalimu Mati, head of Mars Kenya, an anticorruption watchdog. “He has his eye on his legacy. I think we will see more and more heads rolling in the next two years.”

Failure to prosecute

Efforts to prosecute senior politicians accused of corruption in Kenya have so far largely failed, despite Kibaki’s 2002 election promise to cut out graft in public service.

Five other ministers have been suspended or have stood down to face charges. None of the cases came to court, and four of the men regained their political positions.

Ruto becomes the first, however, to face action under the provisions of the new Constitution, approved in a national referndum in August.

He was a close ally of Raila Odinga, the Prime Minister, during the 2007 election, but the pair have since fallen out.

Ruto was shuffled from the agriculture ministry to the far less prestigious higher education docket last year, and is increasingly seen as a powerful figure in opposition to the coalition government’s leaders.

He has announced his aim to run for president during the 2012 elections.

The case against Ruto

The current case alleges that in 2001, Ruto illegally sold a tract of protected forest land outside Nairobi to the national Kenya Pipeline Company for almost $1.2 million. He has denied the accusations.

“You can’t say that the timing is not coincidental,” adds Mati. “There is a sense that after nine years dodging this thing, some level of deferential treatment has been withdrawn. We should celebrate the fact that our new systems are working, but we shouldn’t be naïve that all his peers facing similar problems will be dealt with in the same way.”

Ruto, the most high-profile politician from former President Daniel arap Moi’s Kalenjin tribe, has accepted the president’s order, which has calmed potential for a violent reaction among supporters.

“I don’t necessarily agree with the decision taken by the principals, but the decision they took is not entirely unreasonable considering the circumstances,” he said on Thursday.

He called for a speedy conclusion to the case. If cleared, he can return to government, and during the court proceedings he is not required to stand down as a parliamentarian.

But with 97 percent of Kenyans telling Transparency International that corruption is “a major concern” to them, Ruto may find that if his case is still before the court ahead of the next election, his supporters may desert him, Mati added.