Fighting in South Sudan

A month of fighting in the world's newest nation has killed more than 1,000 people and forced 125,000 to flee. There are signs that a civil war is brewing, and regional leaders and international envoys are trying to broker peace. The two sides have agreed to talks, but at press time the fighting still raged. What's going on?

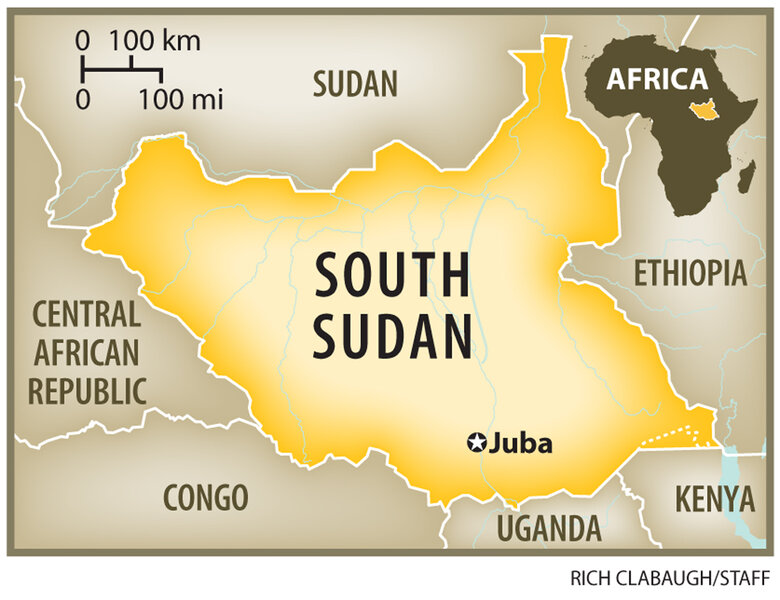

Q: What and where is South Sudan?

South Sudan was the Christian and animist southern third of what was Africa's largest country, majority-Arab Sudan, until it broke away to form an independent nation in July 2011. It is a poor, landlocked state in Central Africa, bordering Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Congo, and the Central African Republic. It has a population of roughly 11 million. Government revenues come almost exclusively from oil sales, but the vast majority of South Sudan's people are subsistence farmers. Health, education, and social development indicators are all among the world's worst.

Q: Who is fighting whom, and why?

Broadly, the supporters of former Vice President Riek Machar have taken up arms against the government of President Salva Kiir. The former vice president is from the Nuer tribe, South Sudan's second largest, and the president is from the largest tribe, the Dinka. The two ethnic groups have a history of mutual antagonism.

Mr. Kiir fired Mr. Machar and a number of his political allies in a government reshuffle in July, and since then Machar has repeatedly accused his former boss of ruling like a dictator. Recently, he said he would challenge Kiir for the top spot in elections scheduled for 2015.

That political rivalry turned violent when Machar's supporters within the presidential guard mutinied on Dec. 15 at an Army barracks in Juba, the capital. Since then, fighting has spread to half of South Sudan's 10 federal states, and has taken on an increasingly ethnic tinge, with Nuers fighting Dinkas.

Q: Wasn't there a civil war there before?

Yes, but that was in Sudan. People in the south of the former nation (in the territory that became the country of South Sudan) fought for decades to win independence from their Arab rulers in the north. To do that, they formed armed militias drawn from each tribe, which eventually banded together to form a unified southern rebel force, called the Sudan People's Liberation Army. That has since morphed into the political party ruling independent South Sudan, and into its national Army. Because its elements are still drawn from different tribes, the seeds were sown long ago for the current outbreak of ethnically charged violence.

Q: Who is doing what to try to end the fighting?

African leaders are spearheading efforts to bring Kiir and Machar to the negotiating table. Kenya's president and Ethiopia's prime minister were in Juba recently to lay the groundwork for talks, and the African Union has said that Machar must order his fighters to lay down their weapons and enter talks to air his grievances. Machar has said he's willing to talk, but insists that half a dozen of his jailed supporters must be freed first, a precondition Kiir has rejected, resulting in an impasse. President Obama sent Ambassador Donald Booth, the US envoy for Sudan and South Sudan, to Juba to encourage discussions, and Norway and Britain have sent emissaries as well. Those three countries were central to the peace talks that ended the original Sudanese civil war, and each has invested heavily in making the idea of an independent South Sudan work.

Q: What are the possible outcomes?

The ideal outcome is a cease-fire with both men sitting down for talks that result in Machar and his allies coming back into government for the final 18 months before elections. There is little appetite among ordinary South Sudanese for prolonged fighting, and it's likely that some kind of coalition will be formed. However, there is the very real possibility that Machar does not have full control over the gunmen ostensibly fighting for him, and they may not heed a call to lay down arms.