With its first mobile library, Uganda starts to build a reading culture

| KAMPALA, UGANDA

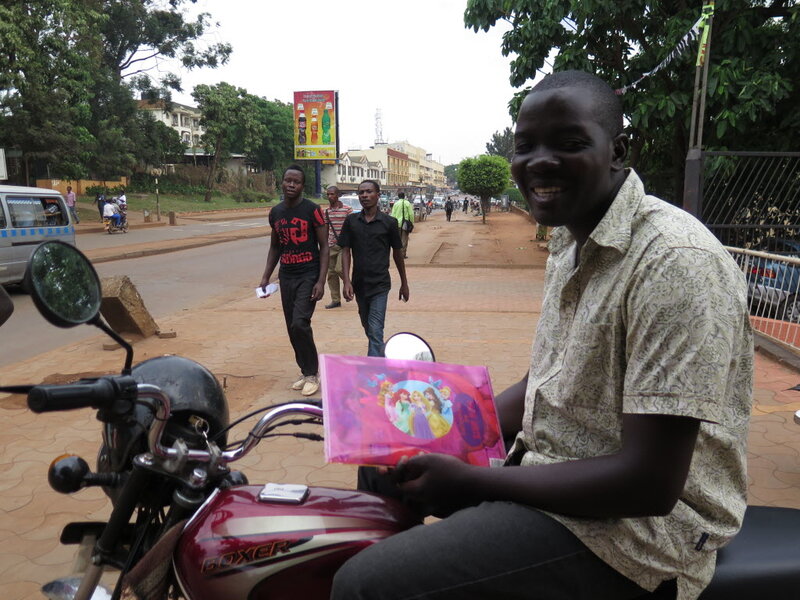

Clutching a pink plastic folder holding copies of books like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and Busy Bear, John Katalaga climbs onto his motorbike taxi, ready for another mission.

His destination is 30 minutes away, where an excited seven-year-old waits for her weekly delivery of three books.

Mr. Katalaga drives a motorbike taxi, or boda boda as they're called here, to deliver books in and out of Kampala as part of the Malaika Mobile Library – the first of its kind in Uganda.

“I like doing this job,” he says, bracing himself for the afternoon gridlock. “I like that children are reading books now.”

Children are the primary borrowers of this mobile library, which was always the aim, says Rosey Sembataya, who founded the venture in late 2014. As an English teacher and owner of a publishing house, she has seen firsthand how hard it is for children in Uganda to gain access to reading material, and how that handicap has trickled down into the classroom "where the effects of not reading are [so] glaring it hurts," she says.

The numbers agree: Only 18 percent of Ugandan third graders could read a second-grade-level English story, according to a 2013 report by Uwezo, an initiative that works to improve literacy among East Africa's youth. The numbers, Uwezo says, puts Uganda far below the 34 percent East African average.

“Overall, of the three East African countries, Uganda’s children were the least competent,” says Uwezo’s Mary Goretti Nakabugo.

Ms. Sembataya sees her mobile library, which send books as far as northern Uganda, as a small solution to a lack of access to children's reading material, and a way to build a reading culture – “a generation of book guzzlers,” she says.

Indeed, the state of Uganda’s reading culture has been up for debate since a prominent Ugandan writer called the country a “literary desert” in 1969 after comparing it to other African countries. And though many Uganda writers have argued against this diagnosis, others say that the lack of government supports towards libraries and the arts in general is a symptom of a larger national disinterest.

"If the reading skill is not developed by the time the child is seven or eight, they will struggle to develop it," Sembataya. "If they can start reading now, we're going to build a generation of adults who love reading, and adults who write."

'Good libraries are missing'

Through the Malaika library, parents pay about $30 a year to borrow up to three books a week from a catalogue of about 500 books. With books costing up to $3, this offers huge savings for parents who want to instill a love for reading in their children.

“Books are expensive [in Uganda],” says Sembataya.” I find it difficult to buy books for my nieces and nephews.”

Beverley Nsengiyunva signed her two daughters up for the mobile library in January. One recent weekend afternoon, her four- and seven-year-old daughters laid out books like A Goat Called Gloria and Jack and the Beanstalk on her living room floor. For her, this is much more comfortable than public library.

"It's a bit too stifling for the children," she says of why she doesn't choose to borrow books from the National Library.

In Kampala, there are just five libraries – three of which are part of the national library system. Nsengiyunva’s daughters would only be able to borrow books from one of them.

At the Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) library library, they hold about 1,000 children’s books, a librariarian says. They range from African-themed picture books to High School Musical. But only 10-20 children a month borrow books from here, despite the free membership. Forty children a month now borrow books from the Malaika program –which is much smaller.

"Good libraries are missing in Uganda, and the existing ones are neglected in a sorry state,” said former higher education state minister John Chrysostom Muyingo in 2012.

"The books in the national library are culturally irrelevant," says children’s book author Oscar Ranzo, who has written nine books based in Uganda. "Children may see stories set in America in the snow, but some African children have never seen snow and don't know what snow is. It would be better to see their own environment in stories."

Writing for children

The perceived government disinterest in reading starts at the top. For years, President Yoweri Museveni has encouraged the science over literature. He has publicly called arts degrees a waste of time.

“The government doesn’t stress the importance of reading,” Mr. Ranzo says.

He also believes that there are less children’s books available because few writers are willing to write them. Because the financial rewards are few, most target international awards that often come with large financial winnings.

“African writers are not interested in writing for kids [because] there’s no awards [for children's books]," he says. "It's about validation from Western audiences. They crave that validation more than they do local recognition."

For Sembataya, she is just happy to see the appetite growing among the children who choose to borrow from her. She expects the number of new borrowers to continue growing. For now the biggest problem is that the books come back.

“[The kids are] like ‘can I read it for one more week?’ and you’re like ‘OK, one more week.’ Then they’re like, ‘another week?’”